Humour, sex, and mortality meld to devastating effect in the Polish sculptor's radical Pop art-inspired practice

Who? Sensual, discomfiting, and politically charged, Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow’s art is often understood through the events of her turbulent life. As a Jew growing up in Poland during World War Two, Szapocznikow (pronounced ‘shuh-potch-ni-koff’) spent most of her teenage years in Nazi ghettos and concentration camps including Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. After surviving the Holocaust and enduring the loss of family members, Szapocznikow trained as a sculptor in Prague and Paris. In 1951 she was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which caused the slow collapse of her body and eventual death from tubercular cancer in 1973, at the age of 47. In 1963 Szapocznikow began to produce the colourful work based on distorted casts of bodies for which she is now best-known. Her art occupies a place somewhere between anguish and pleasure, sex and death, humour and self-degradation.

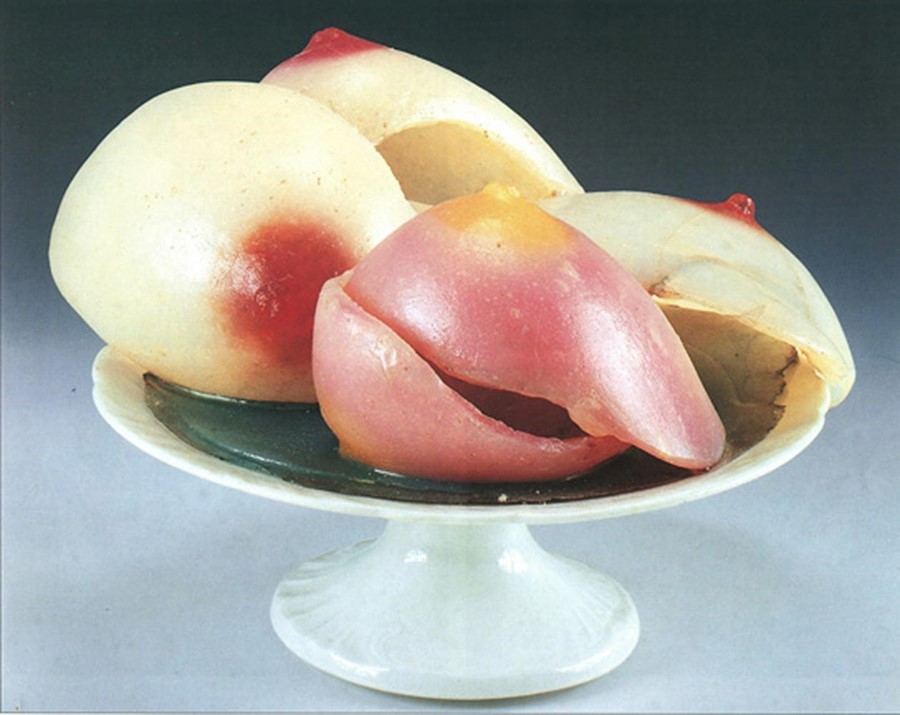

What? During the 1960s and 1970s Szapocznikow created a radically different and new form of sculpture. Drawing on the brightness of pop art, alongside late, dark Surrealism, casts of body parts such as breasts, lips and bellies are presented in dessert bowls or on light fittings. Sculptures lean precariously, almost toppling, or droop, drip, and sag. The effect is unsettling, playful, and seductive: Szapocznikow dubbed these sculptures her ‘awkward objects’.

Though influenced by the circle of artists gathered around Pierre Restany and the Nouveaux Réalistes in Paris, such as César and Niki de Saint Phalle, Szapocznikow’s practice is unique. Works such as Sculpture – Lampe VIII (1970), which placed a woman’s sultry pout atop a working desk lamp, explored the fetishism of advertising and consumerism and the status of the female body in contemporary culture. Using non-traditional industrial materials including polyester resin and expanding polyurethane foam, her works are often fragile, mirroring the tragic frailty of human flesh— of which Szapocznikow was all too aware. The Tumeur series (1969) explored the breakdown of the body through cruelty as well as illness, by superimposing photos of concentration camp victims onto cancerous-looking lumps. Other works are provocative and beautiful, erotic in spite of their strangeness: in her fetishistic Dessert series (1970-71), for example, full, parted lips and lifelike breasts are offered up on glass serving platters. Szapocznikow wrote: ‘I am convinced that of all the manifestations of the ephemeral, the human body is the most vulnerable— the only source of all joy, all suffering and all truth.’

Why? If you’re excited by Lynda Bengalis’ colourful polyurethane spills, Paul McCarthy’s visceral casts, or Paul Thek’s wax meat-sculptures, you’ll love Szapocznikow’s work. Despite her superstar status in her native Poland, Szapocznikow has— until recently— been ignored by the international art world. A flurry of major museum shows in the last decade (including a solo retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York) are finally giving her work the attention it deserves. The Tate Modern’s current World Goes Pop exhibition has opened British eyes to eastern Europe’s rich history of politicised Pop practices, and Szapocznikow’s work is certainly more expressive and nuanced than the stereotypical image of Pop art. Exploring issues of sexuality, traumatic memory, and the materiality of the human body, Szapocznikow remains as fresh and topical as ever.