A new exhibition, featuring rare and unseen works, traces the evolution of Goya's spellbinding portraits

Who? Francisco Goya (born 1746) is possibly the second most famous artist to come out of Spain after Picasso, but arguably without whom, the latter wouldn’t have existed. Lauded as the first contemporary artist by latter generations, Goya was a self-taught painter who rose through the ranks of the Royal Palace in Madrid, but today is mostly known for his macabre etching series The Disasters of War that depicts the atrocities of the battles between Napoleon and the Spanish, through grizzly beheadings and dismembered corpses strung to trees, or perhaps his Black Paintings that show witches' covens, the heads of babies being bitten off and dogs drowning in quicksand. It has long been argued these fantastical pieces were a result of his combined blindness, deafness and madness, but no one really knows. His later, twisted and dark works were never intended to be shown to the public, but illustrate a man troubled by his surroundings, who sees internal visions that aren’t normal. These later works seem analogue to his joy-filled portraits, giving the impression he was a man of split personalities.

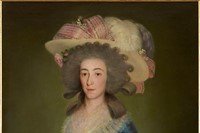

What? Now, a new exhibition at the National Gallery brings together 70 portraits from global collections, many unseen before, to explore the chronology of Goya’s development as a portrait painter to the elite of his time. The first works showcase his initial ambition – tell-tale calling cards with his contact details are subtly painted in to the scenes falling from the artist’s pocket – old school advertising at its best. As his social climbing progresses, his subjects become more at ease and Goya becomes famous for capturing the relaxed, rather charming side to his sitters. A full length portrait of the Duchess of Alba shows just how much his patrons liked him – the eccentric beauty, dressed in diamanté studded gold cloth covered in black netting, subtly points to the sand by her feet, where she's drawn in it “only Goya, 1797”. Perhaps she was referring to him as the only artist worthy of her time, or maybe it alludes to extra-marital goings on. The exhibition charts his move to France, fleeing the Napoleonic rule of Spain, where he begins to paint much more intimate and solemn portraits of his exiled Spanish friends. These works start to show the signs of a man becoming disenfranchised with the aristocracy, as well as someone loosing their sight and with a shaking hand. His final portrait, painted not long before his death, is touchingly of his grandson.

Why? One stunning and rather intriguing picture in the final part of the show is a self-portrait showing Goya being administered medicine by his physician, who we know from his letters he thanked for saving his life at the time. Painted while delirious from the drugs, the image shows a series of almost Francis Bacon-esque men, leering from the darkness in the background – perhaps clergy preparing his last rites or ghoulish apparitions. It perfectly circumscribes Goya’s nervousness and unease at the time. This work brings together his two different styles in a harrowing vision – portrait meets nightmare. This exhibition, while not including, or even mentioning his later existential works, does hint that while Goya succeeded in his ambitions as a talented court portrait artist, the money and the fame turned out to be not be enough.

Goya: The Portraits is at the National Gallery until January 10, 2016.