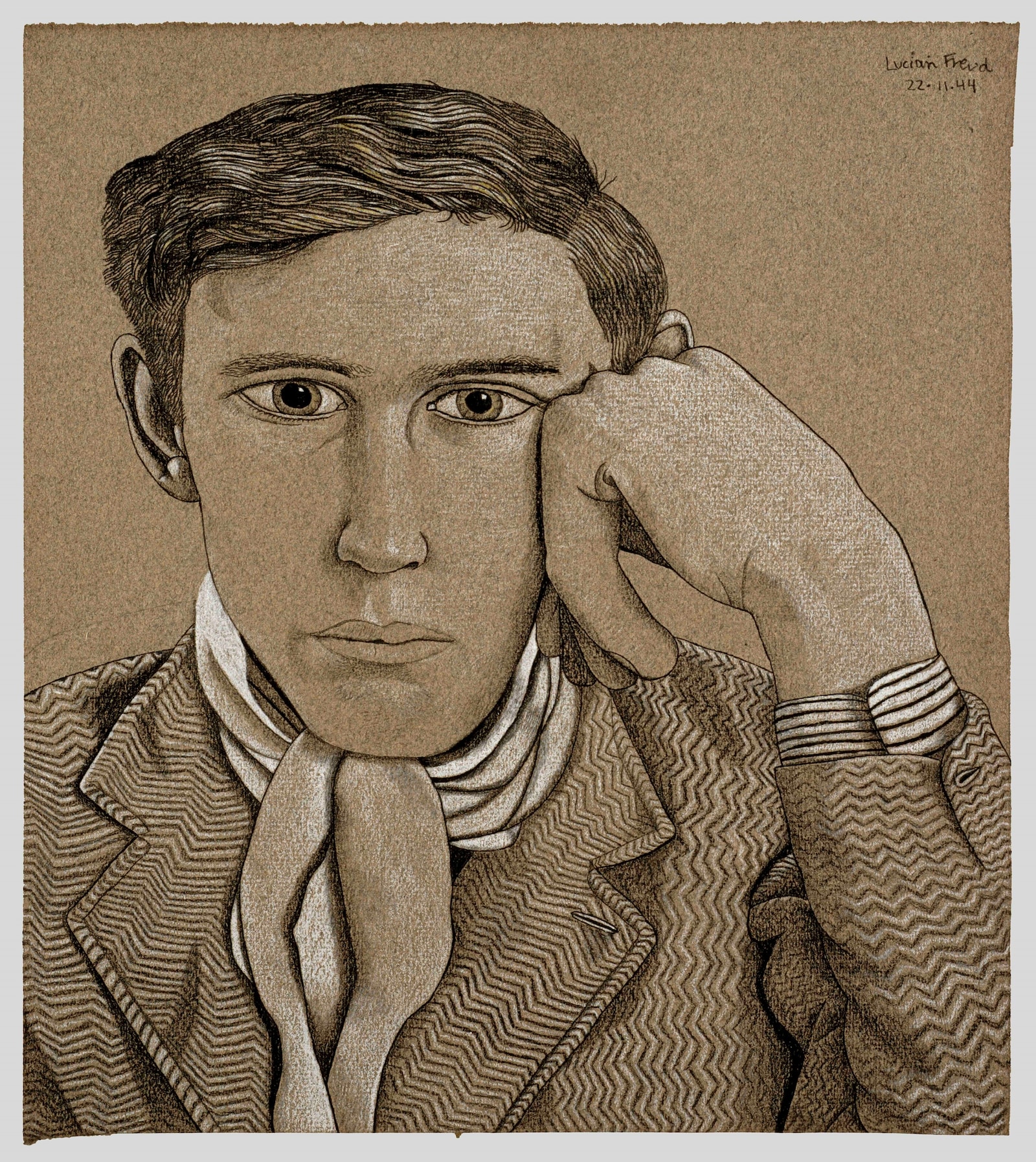

Spanning drawing, etching and painting, the National Portrait Gallery presents Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting, bringing together around 170 works from its archive and key loans – many seldom seen before. Curated by Sarah Howgate and David Dawson, the exhibition foregrounds Freud’s working process across different media, with a particular focus on drawing and etching. Alongside paintings and works on paper, it includes 48 sketchbooks, letters, and unfinished works that Freud created throughout his life, with drawings made from as early as age six.

The display offers an unusually close view of his methods and thought processes. In later life, Freud returned to drawing through etching – often making studies directly from finished paintings, using the plate to isolate a section or motif and push it into sharper focus. Works connected to Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau) (1981–83) show this reverse movement in depth. Throughout, the exhibition reads as biography as much as technique: sitters include close and creative companions – David Hockney, John Craxton, Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach – as well as family members, including his first wife Kitty Garman, his second wife Caroline Blackwood, and his children. Fashion designer Bella Freud, who sat for her father on various occasions over more than three decades from age 17, appears across ten works, several of which are on display.

Describing her father as a life force and anchor, Bella and Lucian became inseparable during these years of late-night dinners, trips to Zanzibar, and gruelling yet rewarding studio sessions. Below, she reflects on the exhibition and talks about coming to know her father through the act of sitting for him: growing up, in a sense, inside the work.

SR: When did you first start sitting for your father, and how did that shape your relationship?

BF: We didn’t grow up together. Our relationship grew out of my sitting for him from about 17, shortly after I moved to London. Sitting for him meant growing with him and being part of his world. The first oil painting [Bella, 1980-81] I sat for as a young woman is in the exhibition – apart from me as a baby [Baby on a Green Sofa, 1961] – and it’s when I really got to know him. It means a lot to me.

SR: What would a typical day or night in the studio look like?

BF: It was exciting. He made it enjoyable for the sitter. I did mostly night pictures during that period, arriving before dawn. We’d have tea, chat, get dressed, and when the light was right, he’d say, ‘Let’s start.’ We agreed on a pose and worked in 45-minute intervals followed by 20-minute breaks.

SR: Did he share stories with you while you sat? What would you talk about?

BF: While I sat, I’d ask about the Paris scene and he’d tell me stories. He had an extraordinary memory – he could recite whole poems by Rudyard Kipling and passages of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. We talked about books too; the whole family once read Honoré de Balzac together. I didn’t do formal academia, but I read constantly. That became a shared world between us.

SR: Did you have any recurring rituals outside of sitting?

BF: Sometimes we’d work until 11pm, then dash out to eat – by cab, or he’d drive, incredibly fast. If we went to Zanzibar, it was never to meet people. He was shy, very private. We were a funny couple of hawks observing – he had piercing eyes that scanned the room; a lot of tension in his demeanour. Being his sidekick was exciting.

SR: What role did Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach play in your experience of him?

BF: They were part of his circle in the 50s and 60s – Francis, Frank, and Michael Andrews – long lunches at Wheeler’s, there’s even a great photograph. For a time, Lucian and Francis were very close; he admired his practice, radicalism and wit. I’d listen to them talk about painting in this non-academic, physical and coded way – a world that only reveals itself to its makers.

SR: Was the studio a social space, too?

BF: The studio was quiet – he hated distractions. It was us two, and occasionally he’d put a record on and we’d dance. He liked Fats Waller and Eddie Cantor, and he would sing I Lost My Sugar in Salt Lake City in a tuneless voice; it was so funny. Once we went to a Johnny Cash concert at Shepherd’s Bush Empire – he was restless and we left early to work. His life was painting, but he liked the occasional adventure.

“When the painting wouldn’t go the way he wanted, he’d get agitated, but he never gave up” – Bella Freud

SR: Did you witness a transition in the way he approached his artistic practice?

BF: His paintings grew in scale. He’d start with a sketch and then expand the canvas, sometimes adding to it when the image outgrew the frame. That shift coincided with the large-scale paintings of Leigh Bowery. We both adored Leigh: he was thrilling, fiercely intelligent, visually extraordinary. Leigh taught him about gay codes, which amused Lucian; they were hilarious together.

SR: Bowery’s passing must have been especially difficult for Freud.

BF: The last painting was exhibited at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 1994. Leigh came from hospital – that was the last time I saw him. It was one of the few times I’ve seen my father crying. Devastating.

SR: What did you take with you from being so enveloped in his way of working?

BF: Perseverance. When the painting wouldn’t go the way he wanted, he’d get agitated, but he never gave up – returning, adjusting, rethinking, until the work held its own. I took that with me: if something isn’t working as you’re making it, you don’t let it go until it reveals itself.

SR: Do you have a particularly fond memory of him that stays with you?

BF: He came to my shows even though he despised being photographed. That loyalty meant everything; he felt like an ally. And then there was the day he pulled out a sketchbook and drew a tiny head of Pluto – my whippet, then his – and wrote my name above and below in a little square. It became my logo. We didn’t have a conventional parent-child dynamic, but he was a life force and anchor for me in an untraditional way.

Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting is on show at the National Portrait Gallery until 4 May 2026.