A new exhibition mixes Don McCullin’s scenes of violence and suffering with still-lifes, landscapes and photographs of Roman sculptures. It’s an exercise in escapism captured with the same heightened dramatic eye he once brought to the front line

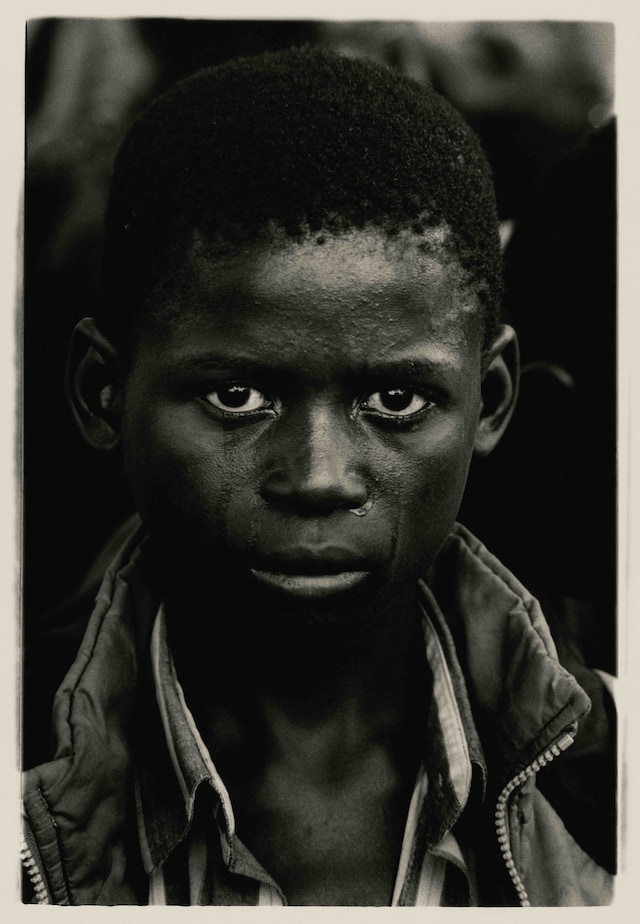

As he turns 90, Don McCullin has been drawn into reflection. People want to hear from the British photographer – he rejects both labels ‘war photographer’ and ‘artist’ – who survived a gun battle in El Salvador, was imprisoned by the Idi Amin dictatorship in Uganda, and used his camera as a shield under fire during the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. His six-decade career has passed through, and recorded, the Bogside gassing in Northern Ireland; mass starvation during the Biafra war in Nigeria; and the civil devastation of Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. We are drawn to what figures like McCullin have learned by living through events and histories many of us encountered at a distance – through his photographs, behind the safety of the newspaper pages they are printed on and the gallery walls on which they hang.

Looking back over that life, the word “guilt” keeps cropping up – a condition McCullin has fought hard to escape. Guilt for surviving, and guilt that years spent in war-torn regions appear to have done nothing to slow the forces still tearing the world apart, or to shock audiences enough to truly see the damage inflicted and refuse its repetition. But this reckoning is not new. The same frustration ultimately ended his 18-year tenure at The Sunday Times after Rupert Murdoch’s takeover in 1981. Writing later in his autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour, McCullin recalled his growing disillusionment with the paper’s changing priorities. “It’s not a newspaper, it’s a consumer magazine, really no different from a mail order catalogue.” As some of the decade’s defining crises unfolded – the Falklands War, the 1983-1985 famine in Ethiopia, and the intensifying anti-Apartheid struggle in South Africa – he was no longer sent. “They certainly don’t need me to show them nasty pictures,” he wrote in Granta (a piece later picked up by The Guardian). “I should wise up: what is the point of killing yourself for a newspaper proprietor who wouldn’t bat an eyelid on hearing you’d died.”

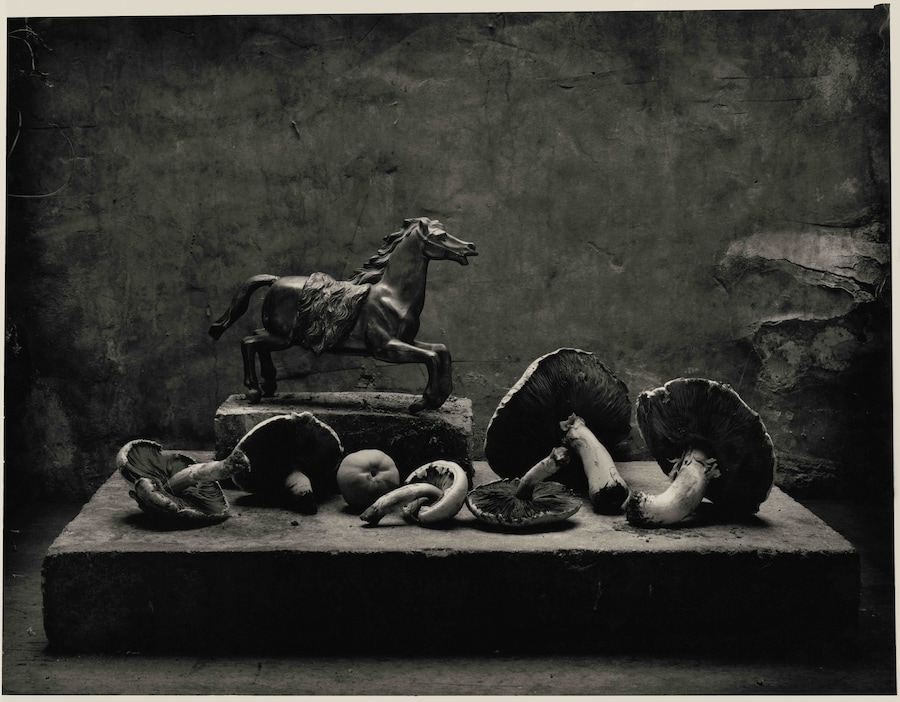

Over time, another reckoning followed: a growing unease about the act of taking itself, and about entering other people’s tragedies uninvited. This reckoning drew him, in later life, towards subjects that do not require intrusion. He gravitated toward the English landscape – the storm-bruised skies and skeletal trees that surround his home in Somerset – and towards still life, which he describes as an even deeper form of escapism than his landscapes; arrangements he makes in the stone shed behind his house. And then there are his photographs of Roman sculptures, taken in museums around the world, a fascination born out of travels in Algeria in the 1970s, and was reignited in the mid-00s through journeys across western Turkey with the British author and historian Barnaby Rogerson. “I could stand for the rest of my life in the shadow of Apollo’s shoulder or Diana’s bow to banish all insecurity and pain,” he wrote in The Oldie. “Here, now, I can practise patience, which for me is a kind of therapy.”

Now shown in the UK for the first time, McCullin’s photographs of Roman sculpture sit at the heart of Broken Beauty, a new exhibition at The Holburne Museum in Bath (with a forthcoming exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset). Organised loosely chronologically, the exhibition threads landscapes, still lifes and these museum studies through the sequence of his war photography. In stone and landscape, he’s found subjects that can be approached through admiration rather than imposition. They are an exercise in escapism captured with the same heightened dramatic eye he once brought to the front line. And, as the title attests, McCullin has a continued preoccupation with ideas of heroism and brokenness, embodied here in classical gods and victors who have outlived pillage, upheaval and disfigurement, preserved by museums and made visible by McCullin’s lens.

Zigzagging through the 50-odd black-and-white photographs – from his 1958 breakout image of a gang of young men in a bombed-out house in Finsbury Park, the neighbourhood he grew up in, to his more recent journeys into the basement vaults of European museums – those continuities become visible. A Turkish gunman emerging from a cinema, captured in his 1964 coverage of the Cyprus Civil War, is held mid-strike in a moment of drama, so perfectly timed, it could pass for a poster still from a Scorsese gangster film.

A few photographs on, the same precision governs The Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury (1994) and Hadrian’s Wall, Northumberland (2009) – captured as the sun climbs and presses against mist and cloud, hinging on moments that would dissolve if taken a minute before, or a minute after. Imperial busts photographed head-on at the New Carlsberg Glyptotek – broken noses and pockmarked surfaces – find a human counterpart in the vacant stare of the shell-shocked US Marine in Vietnam, one of McCullin’s most recognisable images. In his photograph of Artemis’s surviving feet, taken at Istanbul’s Archaeological Museum, the fragment carries the weight of who she once was: a warrior and protector. Much the same is true of his 1961 image of an officer’s boots near Checkpoint Charlie which stands in for the man himself, and for the moment he inhabits.

“I have spent the better part of my life covering conflict, war and tragedy,” says McCullin. “I often ask myself whether I am really breaking new ground, or am simply repeating the same subject matter – broken bodies and minds, in marble, instead of flesh and blood.”

These statues, McCullin has written, come alive only when under the public’s gaze; when the lights go out and the doors close, they return to silence and obscurity, buried once again. It’s a remark that reaches beyond the museum. Next month, he will travel to the Vatican. There is talk of Antarctica too – both are, in different ways, sites of preservation that educate us about where we have come from and our place in the world. Whether in the weathered surfaces of ancient sculpture or in the retreating edges of melting glaciers, what is not looked at – or not recorded – risks staying buried, abstract, and slipping out of view. Broken Beauty distils what has shaped McCullin’s career: a determination to stop forgetting from happening.

Don McCullin: Broken Beauty is on show at the Holburne Museum in Bath until 4 May 2026.