A new exhibition in Berlin spotlights the late artist and auteur’s esoteric, ever-present artistic vision and its inextricable link to his cinematic oeuvre

An ant-infested ear lying nestled in the grass; a pair of tweezers slipping beneath the fingernail of a lifeless hand; a red-eyed, scorched-faced figure lurking behind a diner dumpster. Before he was a filmmaker, David Lynch was a painter and, if you’re familiar with his esoteric filmmaking practice – peppered as it is with some of cinema’s most indelible imagery – it all makes a lot of sense. A year after the auteur’s passing, a newly opened show at Pace Gallery’s Berlin space, Die Tankestelle, foregrounds Lynch’s career-spanning fine art practice and its inextricable link to his cinematic oeuvre.

As a child, Lynch drew and painted endlessly, declaring his intention to become a professional artist at the age of 14. He would go on to enrol in – and drop out of – two art schools before transferring to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 1966, where he thrived as a painting student. As well as taking influence from his instructors and peers, Lynch fell in love with the city – at that time a beacon of urban decay, filled with industrial ruins and weird visual juxtapositions.

During his studies, Lynch famously had a vision of the wind ruffling the grass of a static painting he’d made, and was moved to create his first moving image: a one-minute film called Six Men Getting Sick, featuring six Baconesque heads spewing out liquid. “I started out being a painter and the film came out of wanting to make a picture move,” he said in a 2014 interview. “So I always say the same rules of painting apply to a lot of cinema, and you could say that films are moving paintings that tell a story with sound.”

For Oliver Schultz, chief curator at Pace and one of the main instigators of the Berlin exhibition, a key aim of the show was to highlight the overlap not only between Lynch’s paintings and films, but also the recurring ideas that spring up across his creative output at large, from his interest in form and colour to his endless quest into the subconscious. “It’s thinking about how his vision is present in a way that is almost Spinozan,” Shultz says.

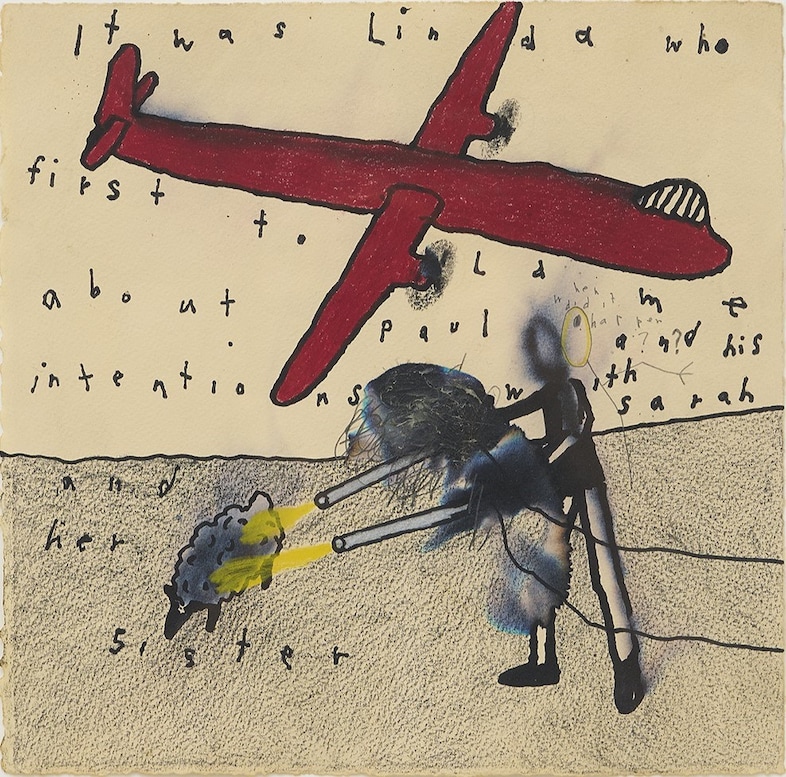

The works on display span paintings, sculptures, watercolours, film and photographs. “In the first room there are just two works: Lynch’s first proper film, The Alphabet – which is a four-minute-long work made in 1968 that’s essentially an alphabet lesson, but also a horror film – and a painting,” says Shultz. In The Alphabet, Lynch establishes an “idea of language as as a space of threat and menace”, something he often did in his paintings too. “It was Linda who first told me about Paul and his intentions with Sarah and her sister,” reads Lynch’s handwritten scrawl, overlaying a painting of a man shooting mercilessly at a sheep as an aeroplane looms overhead. Here, as in so many Lynchian conjurings, individual parts become all the more strange and sinister when combined, giving way to “a pervasive unease that speaks to the subconscious realities of contemporary life” (to quote the exhibition text).

“In a formal sense, there’s this surrealist way of using images – and words – that’s ultimately rooted in Lynch’s work as a painter,” Shultz expands. “And I don’t think you’d know that if you just watch the films, but when you see the paintings, you understand that connection. So, in the first room, we wanted to set up this conversation between the moving image and the painterly aesthetic and methodology.”

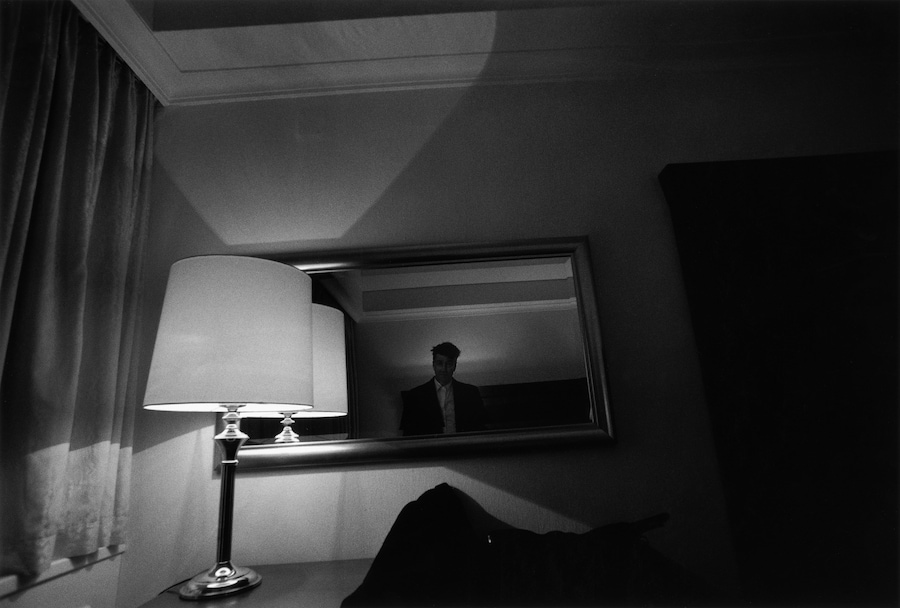

Thereafter, works in the main gallery space explore the range of Lynch’s practice and his sustained engagement with materiality. “Our Berlin gallery was once a gas station that was then converted into a house, and it has a kind of domestic feeling,” explains the curator. The artworks on the ground floor are lit by Lynch’s lamp sculptures, which appear to increase the darkness rather than decrease it, Shultz says, to typically atmospheric effect. “I also carpeted the space with this carpet that feels like it comes from Rabbits [Lynch’s 2022 short, set in a living room],” he adds.

In a wonderfully Lynchian instance of life and time folding in on themselves, hanging alongside paintings and drawings is a series of rarely seen photographs of abandoned industrial sites in Berlin, taken by Lynch in 1999, which hark back to his fascination with the grit, grime and patina of 60s Philadelphia. “The 90s was a period in which Berlin was defined by voids, created by the wall and not yet filled. So there’s this city of voids and this aesthetic of voids – think how many holes and gaps and fissures and anxieties of porousness there are in Lynch’s work,” says Shultz.

So what does Shultz hope that audiences will take away from the Berlin show, which he describes as a kind of “amuse bouche” to a larger show of Lynch’s art opening at Pace’s LA gallery later in the year? “Just how major Lynch was as a painter and visual artist,” the curator answers emphatically. “That his work in painting, drawing and sculpture is every bit as radical, innovative and important to the history of art as his films are to the history of cinema. Even before David Lynch existed, there was a kind of Lynchianness that he discovered, sort of in the way that Einstein discovered the theory of relativity – it’s like he was inseparably connected to it even as he created it.”

David Lynch is on show at Pace Gallery in Berlin until 22 March 2026.