The rising British artist unravels the many layers underpinning his latest show – a mind-expanding musing on shifting states and photographic processes

When the rising British artist Nat Faulkner was a young child, he used to order moths by mail. “You could send off for these caterpillars – cocoons and eggs. You’d hatch them, watch them go through these transformations, and then set them free.” Speaking the morning after the opening of Strong Water, his new solo exhibition at Camden Art Centre, which awarded him the Emerging Artist Award at Frieze in 2024, Faulkner is musing on his enduring fascination with states of transformation. This is a central focus of his fascinating practice, which encompasses photography and photographic processes, as well as sculpture, the medium in which he first trained.

“I’m interested in things that happen on a scale that you can’t measure or see,” says the London-based artist, who is represented by Brunette Coleman. “Oliver Sacks makes a great comment in his text Speed about wanting to be able to see plants move. Take a fern unfurling – no matter how long you look at it, you’ll never see it change. But if you come back two days later, it will have changed drastically. I like that timescale, because it shows you there are things happening that you aren’t able to watch, and that you can’t measure somehow.” The seen and unseen, and the things you can and can’t control, are key themes for Faulkner. They lie at the heart of his new exhibition, where, according to Camden Art Centre, “The constant vitality of metallic substances prevails across distances and state changes, from fixed quantities to new apparitions.”

The exhibition’s first space contains just one artwork, situated in the small Victorian room’s pre-existing skylight, the glass panels of which have been overlaid with bespoke vessels containing iodine solution (the light-sensitive chemical used in early daguerreotype photography). As light filters through the panels, the space is rendered in an oneiric orange hue, the intensity of which changes throughout the day. The state of the liquid changes too, as the shifts in temperature create and dispel condensation, Faulkner tells me, while the iodine will grow incrementally paler as the sun bleaches it. Changeability; the use of materials with a storied photographic history; carefully implemented conditions and a juxtaposing embrace of external forces: this first work is the ideal introduction to what we’re about to encounter, I proffer. “I think it’s a good primer for the rest of the show,” Faulkner concedes.

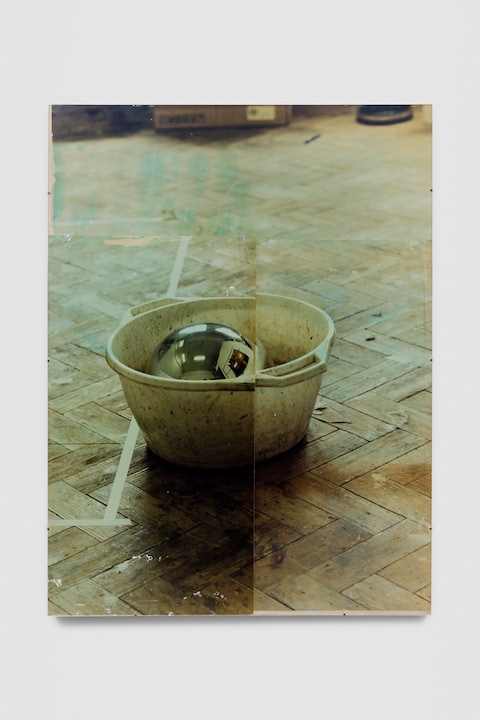

The work inside the main exhibition space – three sculptures and three photographic works – provides enlightening insight into the different facets of Faulkner’s practice, and the multilayered ways he both works and thinks. It is important to know that Faulkner views his studio-cum-darkroom as its own autonomous force – a sort of collaborator in his investigations into the structures and mechanics of photography. He describes his works as “discoveries” more than “creations”: the byproducts of carefully established parameters set within his darkroom (or “machine”) to affect the scale, tone and intensity of his images. “I like the idea of affecting things indirectly, so if I want to do something in my work, I don’t do it to the work itself, I do it to that machine – it’s a very indirect gesture.”

The exhibition’s biggest work, Untitled (Mercury Way, London), is perhaps the best example of this collaboration. It is a vast photograph of a pile of scrap metal, taken in a waste-metal recycling facility in Cremona, Italy, and printed onto strips of photographic paper (in the largest size available), which have then been collaged together. The sellotape with which the artist has attached the negative to the enlarger is included in the print, marked with a visible fingerprint writ large, while the different panels vary slightly in tone according to the times of day the prints were made and the corresponding surges or lulls in the electrical grid powering the enlarger – both examples of Faulkner’s interest in embracing chance and imperfection.

The sculptures on display see Faulkner’s studio in the role of both collaborator and subject, each one a life-size, copper frottage relief that maps a section of its interior – a window, floorboards and part of a wall – via “rubbings”. These have then been electroplated by Faulkner using silver recycled from X-ray film sourced from NHS labs, which will tarnish and change colour over time. “An X-ray is the most invasive type of image you can have taken of yourself – it’s your interior somehow made exterior,” Faulkner explains. “That felt appropriate given that the rubbings render the interior of the studio, a very intimate and internal space for an artist, external.”

The final two works, aptly enough, are a huge monochrome photograph of a dark moth on a white backdrop, and a much smaller colour photograph of the light that Faulkner used to lure it to him. “During and after the Industrial Revolution, the pollution from industrial towns stained the landscape and made it darker, and this predominantly white moth with dark markings effectively changed its colour to a darker pigmentation to better camouflage itself and live longer as a species,” the artist says of his interest in this winged subject. “That felt like a photographic narrative to me – a kind of positive to negative, somehow, from white to black.” Somehow, for Nat Faulkner, it all comes back to shifting states and the alchemy of photography.

Nat Faulkner: Strong Water is on show at Camden Art Centre until 22 March 2026.