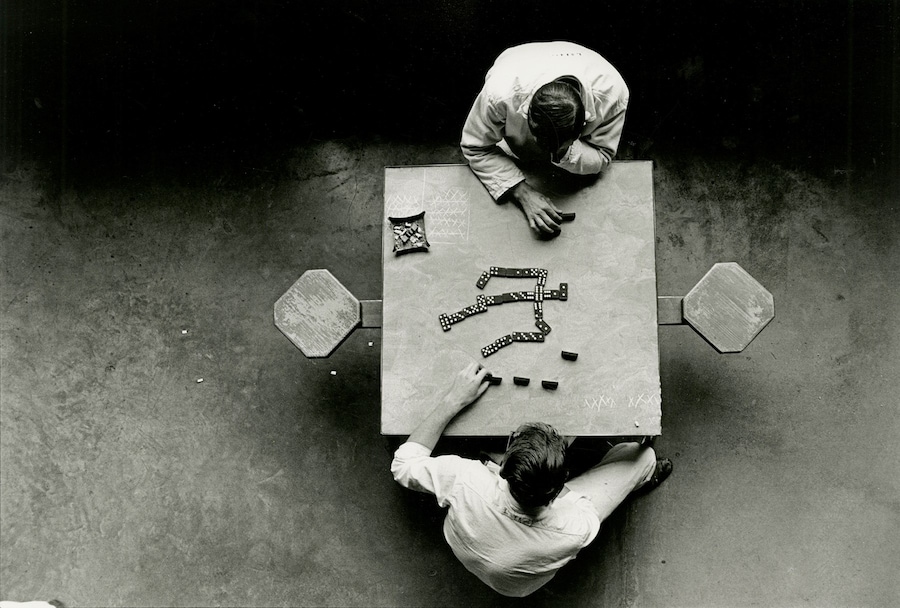

After gaining unprecedented access to seven Texan penitentiaries during the late 1960s, Danny Lyon crafted an unflinching look at America’s notorious prison industrial complex

In a penal system that legalises slavery, who is the real criminal? That question lies at the heart of Danny Lyon’s landmark 1971 monograph, Conversations with the Dead, a masterwork of New Journalism chronicling crime and punishment in the United States. After his work in the Civil Rights Movement and with the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club, Lyon gained unprecedented access to seven penitentiaries inside the Texas Department of Corrections over 14 months in 1967-68 to create a Dostoyevskian journey into the belly of the beast.

A new exhibition, Danny Lyon: The Texas Prison Photographs at Howard Greenberg in New York, revisits this seminal collection of photographs, film, drawings, and ephemera, making for an unflinching look at America’s notorious prison industrial complex. Nearly 60 years later, the work is only more resonant, tracing the long arc of America’s original sin through the lives of the condemned.

The story begins in Galveston, Texas, in late September 1967, when Lyon met and photographed an armed burglar who suggested he hit up the Huntsville prison rodeo held every Sunday in October. Lyon remembers, “I had a press card, so they let me walk right into the rodeo and onto the dirt where the rodeo clowns, bucking horses and prisoners dressed in stripes were performing. As I was shooting, one of the clowns said to me, ‘I can get you inside the prison to take photographs.’”

Lyon returned the next morning refreshed and renewed. “This is all totally opportunism, but that’s how I function,” says Lyon, who used his unimpeachable Queens, New York, charisma to charm the director of the Texas prison system, Dr George Beto, a towering man whose ambitions ran as tall as his Stetson hat. “He wanted to be governor,” Lyon says, “and I was just spinning bullshit as fast as I could. I said it was a wonderful place, that the prisoners were safer there. I told him I didn’t want to just do a story, I wanted to do a book, and he thought it would be great publicity.”

But Lyon had other plans. Looking to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the groundbreaking 1941 book by photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee, Lyon rejected the myth of objectivity in favour of taking a stand and fighting for the cause. But where Agee, who appears in the book as a self-identified “spy”, struggled with the ethics of the gaze, Lyon stared into the abyss. “You have to pick a side,” he says.

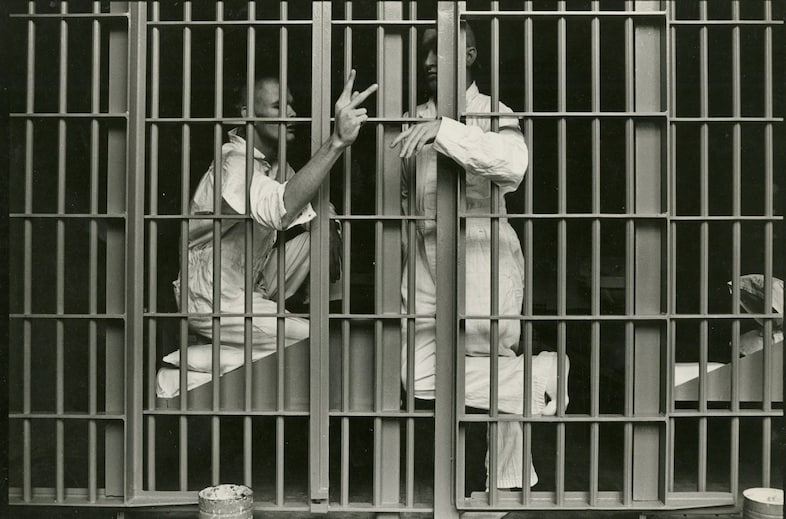

Lyon deftly leveraged his privilege by running game on the “good ol’ boys” who were charmed into giving him unfettered access to the prison system. He remembers the evening of 19 October 1967 as though it were yesterday: “I actually got inside a maximum security unit with two loaded Nikons, nobody following me or telling me what to do. And the moment that happened, I was so happy. As I walked around the yard with these high walls, barbed wire and guns, nobody was around and I could not believe what I had pulled off.”

Just 25-years-old when he entered the Walls Unit in Huntsville, Lyon was the same age as many of the inmates he met, their lives over before they began, now forced into the fields to pick cotton every day under the blazing Texas sun. Free to come and go as he pleased, he spent time with inmates, inviting them to share their stories, and building friendships, some of which would last a lifetime.

Lyon was also given access to their records, some of which he would borrow and copy in the prison print shop, where he would later produce the very first edition of Conversations with the Dead. “I’d say, bring me Jones’s record, because Jones was my buddy. Jones was doing life for habitual and they bought mug shots from when he was 17, 25 and 30 – his whole life story in documents,” Lyon says. “I made the text out of documents. I didn’t think of myself as a writer, so they called it ‘documentarian’, but I don’t identify with that. I was a realist. I wanted to make everything out of real things.”

From the outset, his vision was clear: Lyon would make a book that would bring down the system. And though his ambitions did not come to pass, the prison abolition movement is alive and well today, while Conversations With the Dead stands as a masterpiece of New Journalism alongside Truman Capote’s non-fiction novel, In Cold Blood.

“When I finished the book, I was afraid to show it to Dr Beto because I had two pictures of inmates who had collapsed while picking cotton and I knew he wouldn’t like that,” says Lyon. “I didn’t want it censored. I didn’t want any trouble, so I went into the print shop one night and they printed it as an eight-page fold-up, and we called it ‘Born to Lose.’ They wrapped it in beautiful paper and said, ‘Take it with you, we don’t want any signs of this.’ I walked out that night with 20 copies, which I gave away. I knew I had gotten away with something incredible.”

Danny Lyon: The Texas Prison Photographs is on show at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York until 31 January 2025. Conversations with the Dead: Photographs of Prison Life with the Letters and Drawings of Billy McCune #122054 is published by Phaidon.