“I’m drawn to the depth and strangeness of things,” says artist and psychotherapist Shannon Cartier Lucy as she opens a new show in London

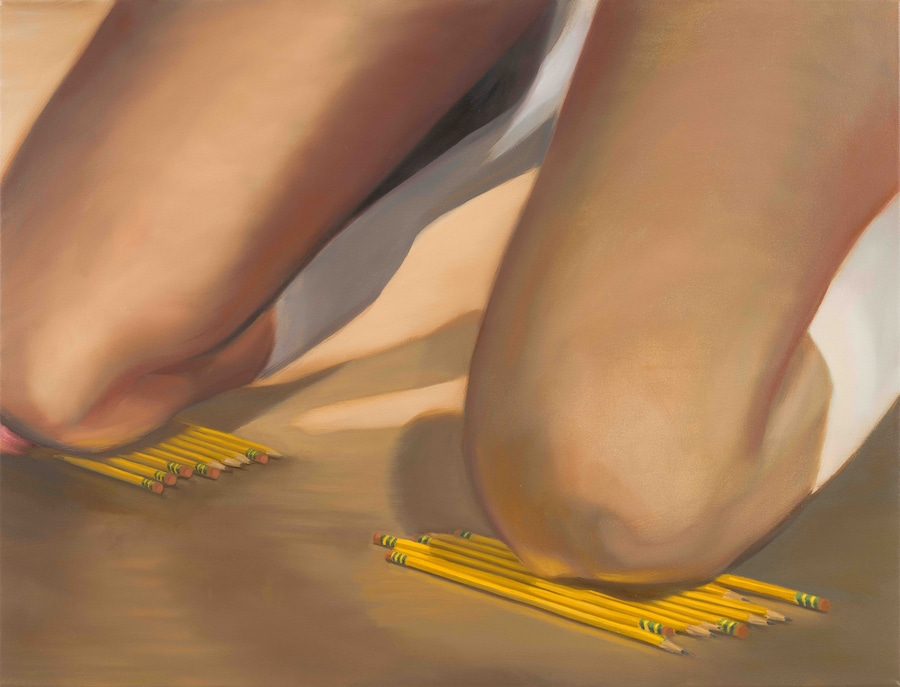

Shannon Cartier Lucy paints alluring and unnerving images. Her scenes are often tightly cropped, focusing on semi-obscured slices of activity around which viewers might fill in the gaps. For her new show, Woman With a Juice Box at Soft Opening in east London, the US artist is exploring uncanny domestic moments. In one work, a child’s pink bendy straw gleams in the foreground, clutched by the close-up fingers of a suited man who fades into the background. In another, a pair of bare legs in white socks kneel painfully on two neat rows of yellow pencils.

“I’m drawn to the depth and strangeness of things,” says Lucy, when we speak ahead of the show’s opening. “I want something that feels slightly uncomfortable. I can tell when I’m looking at a piece of art if the artist was able to let go enough for something strange to come through.” While she does not overly psychoanalyse her images and works intuitively when composing her unusual scenes, she is a trained psychotherapist. This rich understanding of the unconscious mind imbues her work with a surreal edge.

Lucy rarely paints recognisable people. When faces do appear in the work, they are partly covered. “I want to stay away from the viewer’s relationship to the person and keep it about the experience and iconography of the image,” she says. Another piece in the show features a woman clutching a juicebox, her face enveloped by a sheer grey veil and woven hat. “I tried to envision this middle-aged woman walking down the street where you might do a double-take and have all these questions about what is going on.” She enjoys bringing together recognisable, everyday objects with such moments of oddness. “A friend’s child said something which I love, ‘I know it, but I don’t know it.’ I like it when you feel you know what you’re looking at, but then it doesn’t make sense.”

Many of Lucy’s images have a photographic quality – cropped as a quick snapshot might be rather than a formally composed setup – and she is also inspired by cinema. She looks a lot at cinematic stills and recognises that her favourite movies shape some of her ideas. “I am a cinephile. I’ve been obsessed with films since high school, much more than fine art,” she tells me. “I work viscerally, and I think film has just seeped in. It’s how I see things; it is my visual language.”

She is particularly compelled by the films of Robert Bresson and Michael Haneke. In the latter’s movies Funny Games (2007) and The White Ribbon (2009), there is a potent combination of psychological horror and aesthetic refinement that resonates through Lucy’s work. “There is such a deep spiritual and psychological connection to the viewer. The films themselves are beautiful but also really dark,” she says. The softness and beauty of her paintings similarly allow her to delve into uncomfortable power dynamics without becoming too repellent. “If I’m looking at an image, it will turn me off if it’s overtly rude or horrific,” she considers. “Why would I want to create that relationship with the viewer? My mother is a fan even of my weird, edgy works, and I love that. I’m not going to repel for the sake of rebellion.”

Numerous quotidian objects recur through her work, taking on various roles. In the exhibition, yellow pencils are shown as a painful, punishing item, but she has also utilised them in works that suggest disobedience. A new painting showing at Art Basel in Miami next month features multiple pencils stabbed violently into a table full of brioche and cheese, disrupting the typical calm of the still life format.

Many of Lucy’s paintings contain objects and aesthetics that have been highly feminised or connected with innocence, from the bendy pink straw to white socks and satin ribbons. The imagined purity of these items heightens the unsettling nature of the work, though she stays in a place of uncertain discomfort rather than explicit kinkiness. “I’m not into kinkiness,” she says. “There is a lot of other art with this kind of symbolism, but I don’t mean for it to overtly communicate that. I use it more as a symbol of emotional or spiritual submission … You’ve been invited into this soft, colourful world. You can’t quite put your finger on it, but you find something uncomfortable. That’s a painting I want to make.”

Domestic space is an ongoing theme for Lucy. Her career took off at the start of the pandemic, as the feeling of home changed and its at times constricting nature took hold. She notes that the collective consciousness seemed to bubble over with a feeling she has had for a long time. “I felt a sense of disenchantment my whole life; what are we doing playing this charade of control as a society? When you see it crumble, everyone freaks out so much.” Her work does not comment on specific global events, but she does tap into a very current feeling that things are on the brink of collapse. “I’m trying to submit to this uncomfortable truth that encompasses the beautiful, the ugly, the violent.”

Woman With a Juice Box by Shannon Cartier Lucy is on show at Soft Opening in London until 10 January 2026.