Walking down the eastern end of the Strand in London, Louise Giovanelli’s new public artwork appears like a mirage. St Mary le Strand, a 300-year-old baroque church designed by James Gibbs, has been transformed by the artist, with a vast trompe l’oeil shimmering silver curtain attached to its side. Grand in scale and ambition, Decades is haunting in its strangeness, inviting questions around notions of worship, devotion and history. Like all good public artworks, it is unexpected, hypnotic and ambiguous, providing a moment for pause in the hustle and bustle of metropolitan life.

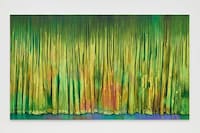

Curtains are a recurring motif for the British artist, who has depicted them on vast canvases in hyperreal, shimmering oil paint in greens, blues and golds. A versatile subject matter loaded with meaning, curtains fascinate Giovanelli for their rich symbolism, tactility, and presence in art history and religious spaces. The artist recalls that, at her first show with White Cube in London in 2022, people came to the gallery just to take selfies in front of her curtain paintings to post on social media. “I’m fascinated by how curtains change people’s behaviour,” she says. “They make people feel like celebrities.” Giovanelli tends to paint curtains from working men’s clubs in Manchester, where she lives (the silver sequined curtain of Decades is named after the Joy Division song of the same name, which happened to be playing at the club when the artist photographed it).

At the heart of Giovanelli’s dazzling paintings of closely cropped film stills, curtains, hair and clothing is an obsession with contemporary modes of devotion. Despite now identifying as an atheist, the artist’s religious upbringing translates into a reverence for the aesthetics of worship – although now, in her paintings, pop culture and celebrities have largely replaced the religious icons of the past. “I’m trying to show people that even though they might not think they believe in a God, they still need this type of worship,” she says. “We have this need to aspire and to look at something and point to something that we consider to be bigger than ourselves.” With its hallucinatory, glowing facade, Decades is just that – a bold melding of past and present that asks us to surrender to something bigger than ourselves, if only just for a moment.

Below, Louise Giovanelli talks about contemporary modes of devotion, her obsession with curtains, and the alchemy of painting.

Violet Conroy: Why did you decide to work with this church for this commission?

Louise Giovanelli: My paintings touch on a lot of religious themes and ideas around iconography, devotion and contemporary modes of worship, so I was selected as an artist who could potentially work in sympathy with the church. I’ve never made a sculpture or done any public art, but I just tried to think of it as an expanded painting. A curtain seemed fitting, since it’s a motif that I keep returning to in my work.

VC: Tell me more about the curtain, and this idea of an ‘expanded painting’?

LG: This curtain was based on a series of paintings that I recently made called Decades, for my show at the Hepworth Wakefield. The curtains in the series are based on a working men’s club in Manchester, where I live. I’m interested in all the contexts in which curtains arise, from the high-brow, theatrical, performative venues to the shady nightclubs and bars and working men’s clubs. There’s a democratic nature to curtains, how they can exist across this span of time. This work is a composite photograph of the curtain in situ, made with a very high-res camera. The lights are also very important, to make it glow. That’s something I consider in painting all the time – the light and the luminosity.

“I’m trying to show people that even though they might not think they believe in a God, they still need this type of worship” – Louise Giovanelli

VC: How do you approach light in your paintings?

LG: There’s something about the challenge of rendering light, and a kind of alchemy involved with oil paint. I learned from the old masters how to try and render these things. How does this artist manage to capture velvet, fur or shiny things like cutlery and jewellery? Part of why we’re drawn to these paintings is because there’s a kind of disbelief – paint is just mud. That is a type of magic.

Light has always been a fundamental part of my practice. I try to make things that are glowing, which also has to do with the religious aspect. So much of Catholicism and Christianity is based on iconography, looking at things that are glowing, shiny and dazzling. We need to look to something that sparkles, so I try to do that in my paintings in whatever way I can.

VC: You’ve been painting curtains for a long time now. What first attracted you to them as a subject?

LG: My initial fascination with curtains was derived from art history and the rendering of fabric. I’m fascinated by how curtains change people’s behaviour. At my first show with White Cube, I had some very large diptych curtain paintings and the amount of selfies that people would take in front of them … White Cube told me that people were coming in and getting changed into outfits in the toilets and coming back to take photos.

When I moved from Wales to Manchester, I became fascinated by the curtains in working men’s clubs and what they stood for in these communities. People do karaoke and bingo in front of them. It gives people their license to have five minutes in the limelight on a weekend, or to sing their hearts out and have a few pints. Curtains make people feel like celebrities. It will be interesting to see how people interact with the new commission. I hope it slows people down and that they look [at it]. It’s got this kind of gravitational feel.

VC: That performative element of the curtain is interesting. It also ties into your interest in celebrity culture and social media.

LG: I’m fascinated by contemporary methods of devotion and worship. I call myself an atheist but I have this reverence for religion because of my upbringing. I’m trying to show people that even though they might not think they believe in a God, they still need this type of worship. Going to a pop concert, for example, and looking at an iconic pop star in a dazzling, glittery dress … we have this need to aspire and to look at something and point to something that we consider to be bigger than ourselves. That’s the same human impulse that’s always been there, but it’s evolved from a religious context to these newer contexts. So I’m interested in visually bridging that gap and showing people that it still exists.

Decades by Louise Giovanelli was commissioned by Create London and is on show in London until 18 January 2026.