A new book traces the revered artists’ compelling two-decade-long relationship through their photographs and intimate correspondence

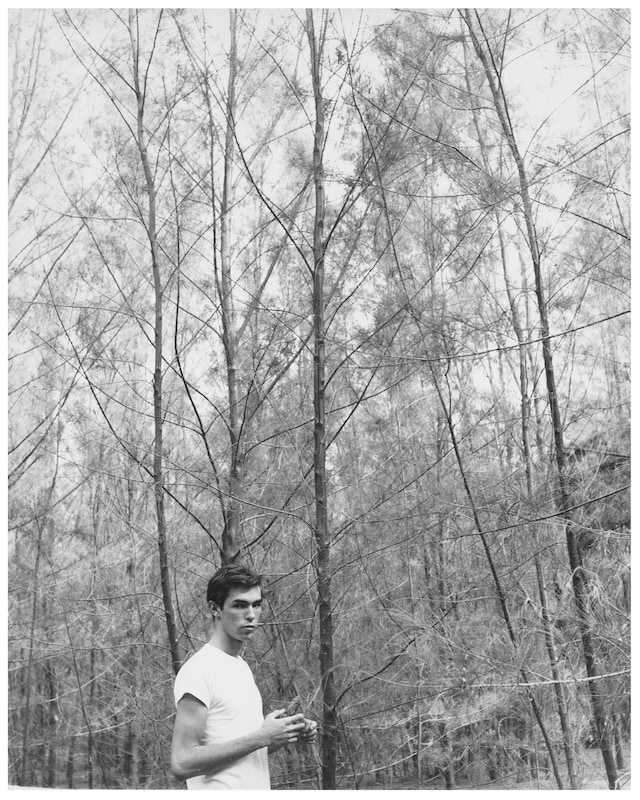

Peter Hujar and Paul Thek first met on a road trip to Key West, Florida, in 1956, with Hujar taking the first of what would become many portraits of Thek. At the moment those pictures were taken, they were two young artists (aged just 22 and 23 respectively) who hadn’t quite yet found their professional footing, still honing their crafts and both in relationships with other people. The following decade would see them become lovers and also take huge artistic strides – Thek becoming a critically acclaimed artist and Hujar establishing himself as a commercial photographer while taking many of the portraits that would cement his status in the canon of 20th-century photography, albeit posthumously. From today’s vantage point – knowing that the pair were on the cusp of becoming embroiled in a romantic and creative relationship which would last two decades – it’s impossible not to invest these early portraits with the kind of portentous meaning very few of us have the gift of intuiting as we move unwittingly through the momentous meetings of our own lives.

From that initial encounter, their fluctuating relationship – part love affair, part friendship, part creative alliance – would endure until 1975, spanning travels across Europe and the US. Their compelling story is partially preserved in their photographs of one another and in a fitful but fevered correspondence (sadly, only Thek’s letters have survived). Now, these precious relics have been gathered together in a new book, Stay Away From Nothing, published by Primary Information.

The book’s editor, Francis Schichtel, was immersed in the process of digitising The Peter Hujar Archive when he became fascinated by the pair. “I went through every roll of film, beginning to end, and saw their relationship unfold in the negatives. I felt like I’d seen all their travels and experiments – not just Peter photographing Paul and vice versa, but all the stories people told about them. Their artistic histories are so interesting, especially because Paul’s most important work is gone, and Peter didn’t become famous until after he died. And yet, people around them kept their story alive, even if nothing was ever totally clear,” says Schichtel. “It all had this mythical, unclear quality, which drew me in.”

While there’s a discontinuity in the conversation – Thek didn’t have a good track record for keeping hold of his belongings – reading one side of the exchange, it feels possible to imaginatively trace the contours of Hujar in the absence of his response. “When I first found the letters in the archive, they were all out of order,” recalls Schichtel. “As I organised them, I was worried it would be a problem that only Paul’s letters survived, but, actually, it makes things more interesting. You fill in the blanks for yourself; you get on Peter’s side – receiving the letters, wondering how he’d feel reading them.”

For Schichtel, one of his favourite examples from the correspondence is a 1961 postcard from Long Island beach. Thek’s circled one lone bather from among the crowds and scrawled on the back, “A photograph of happy persons, except me, I am seen looking for you.” Another particularly memorable section is Thek’s first trip to Europe in 1962, before he meets Hujar in Italy. “The letters from that journey have such a sense of excitement and adventure. There are these bursts, these segments where Paul writes prolifically. That part always feels especially beautiful to me.”

Reading the letters and postcards in Thek’s own handwriting with doodles and annotations feels far more intimate and alive than reading a transcription. “I understood Thek’s work better after these letters,” Schichtel continues. “Academic writing makes him seem so untouchable, but in the letters he’s funny, self-aware, and doesn’t take himself seriously.” This private correspondence shows the artist to be charming, spontaneous, irreverent, and not a little demanding. “Paul is always asking Peter for things!” Schichtel says, “Every letter, he’s got a request. I sometimes wondered if Peter was annoyed!”

What insights can we gain from Hujar’s photography over the course of his relationship with Thek? “You can see him get more serious and figure out what he wanted his work to mean, and it tracks with how he photographed Paul, too – it becomes more experimental, more intimate,” says Schichtel. Yet, while Hujar’s technique becomes more refined, more distinctive, his vision is remarkably lucid from the beginning. “There’s an early photo where Paul is sitting on a couch, his head resting against the wall. It’s beautifully composed, but when you compare it to the later works, that signature style becomes clear. Peter wasn’t reinventing the wheel, but the work feels so him – especially the final photos in the book from the 1970s.”

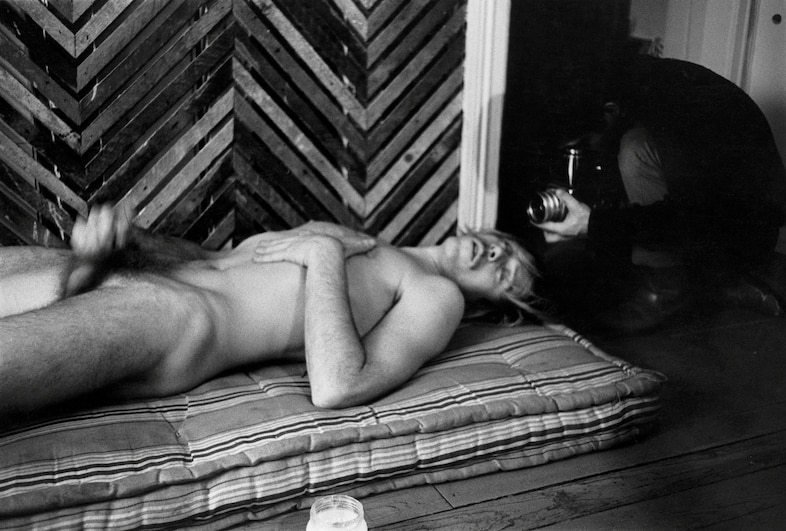

Ultimately, their bond soured around 1975, but the success of a relationship should never be defined purely by its ability to sustain itself forever. Stay Away From Nothing allows us a treasured insight into a significant two-decade-long alliance which enabled both men to push and inspire one another. Thek continually ran ideas past Hujar, and Hujar found a new kind of freedom in shooting Thek, who starred in some of his early nudes and masturbation shots. Their trip to the Palermo catacombs in 1963 would form the basis for Hujar’s deeply personal series, Portraits in Life and Death – the only book he published in his lifetime. And, for Thek, seeing the corpses “used to decorate a room, like flowers” prefigured his “meat” artworks, which would propel him to art world fame.

“One of the questions people keep asking me is, ‘What did they like about each other?’ Well, they were both stunningly beautiful, which shouldn‘t go without mentioning,” Schichtel points out. Aside from everything else, Stay Away From Nothing is an enthralling and glamorous romance. Thek’s letters at the peak of their passion are disarming, captivating, lustful. Like all good romances, it doesn’t end happily, but that’s not the point. “It becomes sad towards the end,” says Schichtel, “but they’re so romantic. That’s the underlying feeling of the book. There’s such a deep love there.”

Stay Away From Nothing is published by Primary Information and is out now.