A new book of Polaroids pays homage to the now-closed Chinese eatery, Davé. “It was the place to be,” says Sofia Coppola

“Nothing was more exciting and glamorous than going to Davé in Paris in the 1980s,” writes Sofia Coppola in the foreword for A Night at Davé, a new photo book published by Idea which pays homage to Paris’ infamous rive droite restaurant and all who frequented during its zenith. “Davé was the place to be.”

Discreetly tucked away behind a red lacquer door on Rue Saint-Roch was a small, dimly lit Chinese eatery, Davé. Its air thick with perfume, cigarette smoke and gossip, Davé was the most fashionable and exclusive restaurant in Paris for three decades, populated by stars from the fashion, film, art and music worlds. Among them: Iggy Pop, Rei Kawakubo, Yoko Ono, Madonna, Jeanne Moreau, Janet Jackson, Jean-Paul Gaultier and Keith Haring. All who went quickly came to know the restaurant’s charismatic owner, Tai Cheung, otherwise known as Davé.

“The place was filled with the fashion and show business of that era, people table hopping and hanging out, platters of Davé’s mum’s Chinese food and Davé taking Polaroids,” writes Coppola, who went with her father when she was a teenager. Francis Ford Coppola was also a regular at the restaurant.

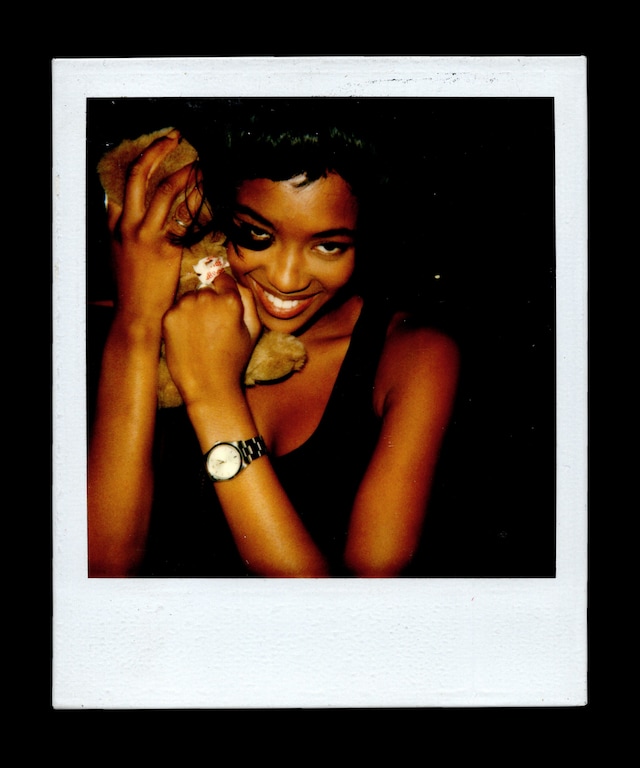

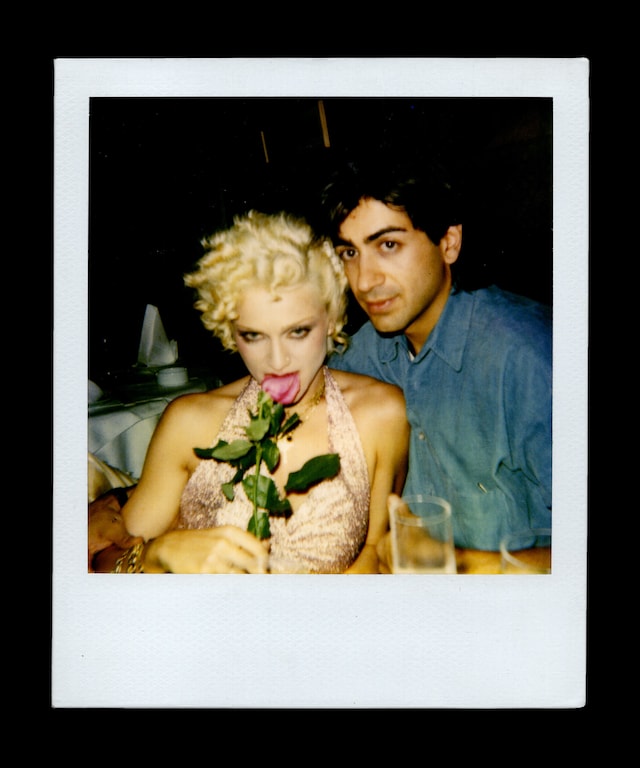

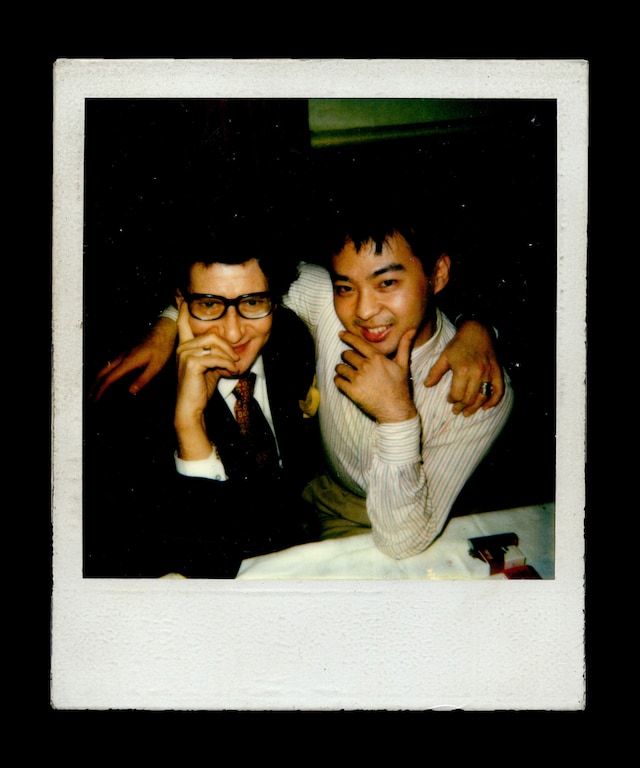

Inspired by Andy Warhol’s Polaroid portraits (and taught by Jean-Baptiste Mondino), Davé photographed his guests with a Polaroid camera, pinning copies of the images up on the restaurant’s walls. It quickly became his very own hall of fame.

Documenting stolen moments with anyone and everyone from Kate Moss to Lou Reed, Davé’s photos are a glimpse into a bygone era, a debaucherous life before social media. “The photos were always meant to capture a memory, to fix a precise moment of happiness,” Davé tells AnOther. “Now everyone does that (and more) with their phones. Back then, it was the Polaroid.”

Now sharing these famed Polaroid pictures (some for the very first time), A Night at Davé is part memorandum, part elegy. Edited by Charles Morin, Boris Bergmann and Davé himself, the book also features other previously unseen ephemera from his personal archive including Keith Haring’s sketches, a note from Henri Cartier-Bresson, postcards from Helmut Newton, an interview with Davé and an epilogue extracted from Jean-Jaques Schuhl’s 2010 novel, Entrée des Fathomes, in which the writer describes the restaurant‘s location.

“We were in a place out of the world, from another time,” Schuhl writes in Entrée des Fathomes. “Rue Saint-Roch feels straight out of the 19th century, with its few scarcely inhabited buildings – ‘It belongs to the clergy,’ Davé once told me – its soot-blackened low houses and the tall windowless walls of the church’s corner façade, from which, even in the evening, the crystalline voices of a children’s choir rise.” In its exclusivity and privacy, Davé was a sacred space of its own, a guarded citadel where people could confess, sans judgement. When the thick velvet curtains were drawn and the bottles were half empty, people felt at home: “One night, Mick Jagger started singing a Dolly Parton song which was playing from the hi-fi, The Coat of Many Colours,” Davé tells us, fondly. “He was relaxed, he sang in a manner that wasn’t serious. He didn’t take himself too seriously. Then there was Nick Rhodes’ birthday. A magical night. Everyone came. Sting. Elvis Costello.”

Before opening Davé in 1982, the Hong Kong-born restaurateur worked at his father’s restaurant in Oberkampf, Pergola du Bonheur, where Vogue’s Barney Wan and Grace Coddington would often dine. Helmut Newton was a regular too, wooed by the quality of its cuisine. After Pergola du Bonheur closed down in 1980, Davé decided to continue his father’s legacy, opening his own iteration in the first arrondissement two years later. His father’s loyal clientele – and their friends and colleagues – were close in tow. “The first [celebrity to come to Davé] was the painter Eduardo Arroyo,” Davé remembers, continuing: “Then there was the actress Aurore Clément with the producer Jean-Pierre Rassam, and Francis Ford Coppola.”

No menus, no set prices, just recommendations – eating at Davé was a famously personal affair. “Food is a support,” he says. “It was part of the whole operation: of welcoming people, offering them this moment; of freedom, joy. It wasn’t ordering food like in a regular restaurant, it was rare and tailored.” And people could stay long after the kitchen closed, when it was no longer about the food, but the feeling. “For me, the feeling is what mattered most. The most important thing was that people felt happy, good and free. At my place.”

“I followed my instincts,“ Davé says of the atmosphere of the restaurant. “And a friend’s advice about the lighting … red, but a little less red than at Maxims’ … just enough to give a pink reflection on the skin and erase any flaws.” Instincts aside, Davé never thought it would be what it became. “I didn’t feel it. But deep down, I wished for it. And my wish came true. I was lucky.” Arranging people, feeding them, then photographing them – Davé was both host and observer, his restaurant like the set of his own film.

Seating was, of course, political. Rumour has it that it was even hierarchical, but Davé won’t concede. “I knew what people liked, what they didn’t, who they got along with. This allowed me not to force things, to make sure everything stayed as natural as possible.” A-listers were tucked away behind the tropical fish tank. “Some people preferred the back so they wouldn’t be seen.” Editors, models and fashion people by the door. Surely drama was inevitable? “Most things calmed down on their own,” he tells me. “Or they left. Saint Laurent stormed out once during a dinner with Paloma Picasso.”

In 2001, Davé moved a few blocks east to Rue de Richelieu near Palais Royal. Davé 2.0 was twice as large and half as exclusive. Service continued, but when the financial crash hit in 2008 and belts were tightened, Davé felt the effect of budget cuts. Over the next decade, outside of fashion show seasons, the stars came less and less, and Davé’s popularity slowly petered out. In 2018, Davé retired and the restaurant closed.

Gone, perhaps, but never forgotten. The restaurant’s memory lives on through photos, stories, even literary prose – and now through A Night at Davé. Making this book was not without nostalgia or pain. “My sadness is seeing the people I loved who are no longer here,” he says, as he reflects on all the nights in all the years that Davé was operating. “Being at Davé was like being in a film sequence – outside of time.”

A Night at Davé is published by Idea and is out now.