A new exhibition at David Zwirner in London features Diane Arbus’s richly psychological and often glamorous portraits of people in their homes

Diane Arbus’s spirited black and white photographs are richly psychological and at times uncanny. Her subjects often return intense gazes to her lens. Many of her images were taken out on the street, but a new show at David Zwirner in London transports viewers inside the sacred realm of personal, domestic space. It is the first show of its kind to focus entirely on Arbus’s approach to private interiors, with photographs from the 1960s until 1971 stretching across New York, California, New Jersey and London. In Spring next year, the show will move to Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, and a monograph has been released as a joint venture between both spaces and the artist’s estate.

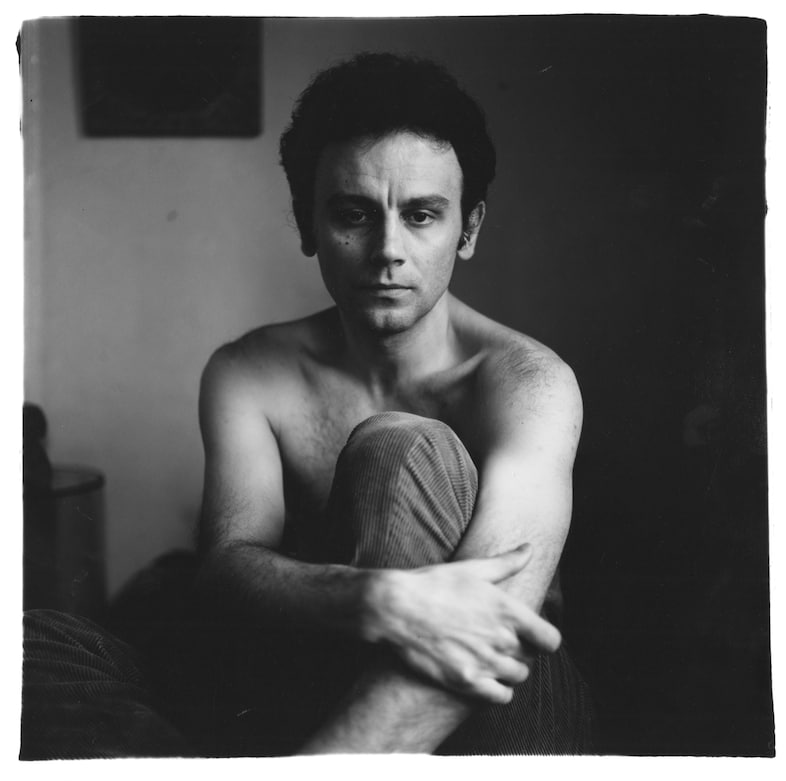

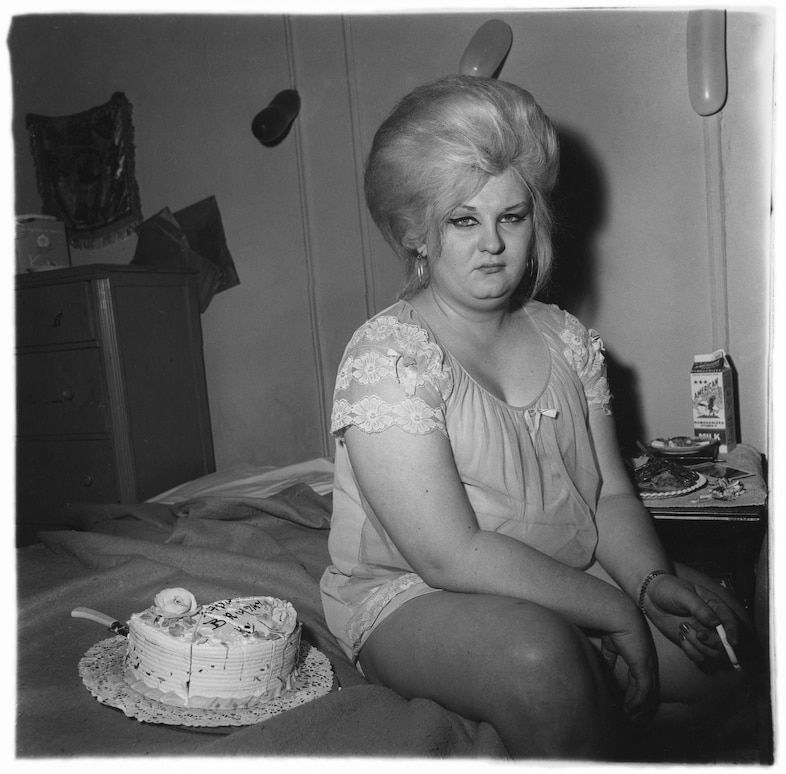

The wild expressiveness of her most famous photographs runs deeply through the pieces in Sanctum Sanctorum, named after the concept of a sacred room or inner chamber. Couples are shown nude and sexually entangled with one another; solo women sit glamorously in bed covered in fine jewellery; a female impersonator curls up on a striped mattress, almost naked except for a coiffed blonde wig and delicate heels. The images are mostly intimate in scale, following a 9 x 6 format until 1961 before moving into Arbus’s signature square 14 x 14 format from 1962. All the works are printed in rich, inky monochrome. As James Green, head of Zwirner’s London gallery tells me, the “eccentric nature of the printing adds to the imagery”.

The exhibition celebrates Arbus as an artist who was able to build a great level of trust with her subjects, allowing her to access their private spaces and ultimately present them with autonomy and empowerment. While many of her images feature individuals photographed in public, Green imagines that she sometimes instinctively felt a drive to move to someone’s home. “I think she immediately sensed there was more to get, should she be able to get inside with them.”

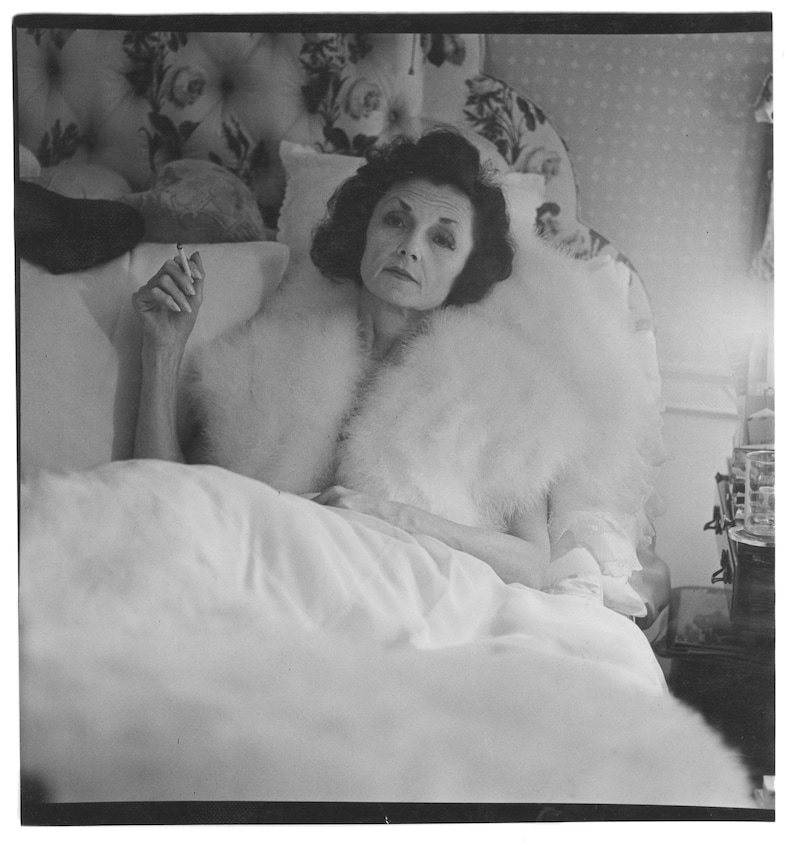

Many images feature her subjects lying on or around the bed. This universal piece of furniture is variously shown as cosy, luxurious, stark and sensual. “There was always an element of allowing the subject to find their own context and space,” says Green. “So I don’t think she was leading people to the bed. But I’m sure that was a happy outcome for her, as it is the most private part of the private space.” Mae West in her bedroom, Santa Monica, Cal. 1965 shows the iconic actress in a moment of pure glamour, dressed in marabou feathers and swathes of sheer fabric, next to her bed which is equally well attired in silky sheets. Conversely, Couple with their adolescent daughter in their bedroom at a nudist camp, N.J. 1963 is almost uncomfortably intimate, showing a nude family wearing nothing but socks and sneakers, next to two rickety metal beds.

Many of the subjects in these images look directly at Arbus – and us. They seem to command their space and image, rather than being perversely observed. They are conscious and welcoming of both viewer and artist, not often smiling but wholly present. The full selection of works reveals a liberal view of society, featuring comfortable, natural nudity, trans individuals, and performers in drag. It reflects Arbus’s own social life and her grounding within New York’s richly creative scene.

“New York in the 1960s was her canvas,” says Green. “Growing up in Manhattan impacted her view of the world, which was profound. These images offer a snapshot of that time, but the diversity also makes it quite timeless. There are threads in the work you could still pick up today. For me, one of Arbus’s great powers is that, while the works are rooted in their time and they are black and white prints, they do not feel like people from another world. We still have a contemporary connection.”

Arbus made little distinction or value judgement between her subjects, treating everyone the same, despite their celebrity or notoriety. Puerto Rican housewife, N.Y.C. 1963 shows a woman with thick black eyeliner, a low-cut black evening dress and sparkling jewellery sitting on the edge of her bed, gazing confidently just above the camera. “There is something very glamorous and star-like about her pose,” says Green. “The photograph we have was printed by Arbus herself and it has some noting and marks on it. That’s a very special print of a work I already love.”

This glamour runs through many of the images, with Arbus’s subjects seeming to revel in dressing up, rather than giving in to the casual comforts of home. Mrs T. Charlton Henry in a negligee, Philadelphia, Pa, 1965 shows an elderly woman bathed in sunlight through her window, draped in silk and pearls with unfathomably tall, curled hair. Brenda Diana Duff Frazier, 1938 Debutante of the Year, at home, Boston, Mass. 1966 features a former beauty queen lying elegantly in bed, soft feathers surrounding her shoulders as she clutches a cigarette.

Despite the at times excessive costume, there is something deeply authentic in the images that can’t always be captured in public space. For Green, this exhibition highlights Arbus’s awareness that, “if you are going to get somebody feeling as secure as they can be, in terms of themselves, their performance, glamour and eccentricities, they need to be in their own place.”

Diane Arbus: Sanctum Sanctorum is on at David Zwirner, London until 20 December 2025.