Produced between 1978-79, the artist’s enigmatic Arthur Rimbaud in New York series sees Wojnarowicz cast the poet as an outsider like himself

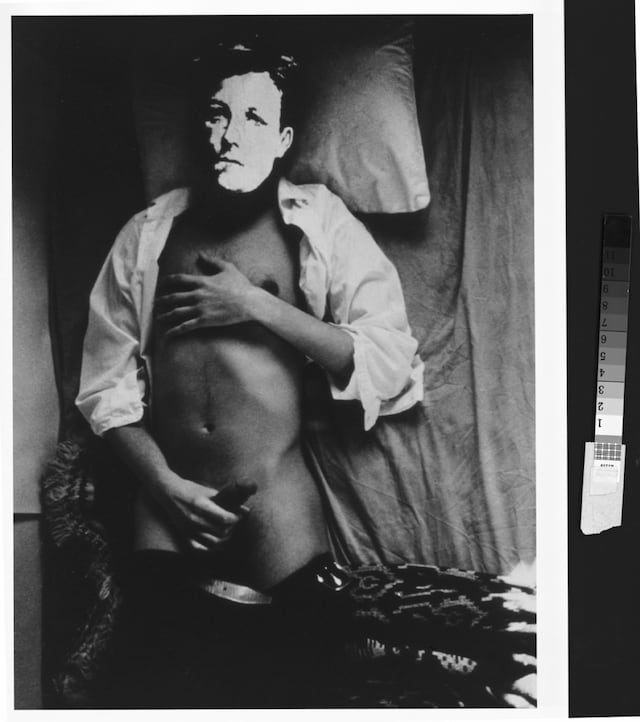

The face of Arthur Rimbaud worn in David Wojnarowicz’s photographs comes from an image taken by Étienne Carjat. In the image, Rimbaud is 17 years old, still a child. Captured like this – and used as material by Wojnarowicz – his youth becomes eternal and symbolic, a lens through which the outsider artist was also able to see himself. The Arthur Rimbaud in New York series, produced between 1978-79, after Wojnarowicz returned from a trip to Paris, sees a small circle of friends, collaborators and lovers wearing Rimbaud’s face, with pictures taken throughout New York City. On the surface, there might not be much in common between Rimbaud’s poetry and Wojnarowicz’s intense, politically furious collages and graffiti, but Wojnarowicz casts the poet as an outsider like himself, unable to find a concrete place in a world that seems more than willing to turn its back on him. This imbues the series with a haunted feeling; the unmoving face of Rimbaud becomes uncanny, ripped out of time.

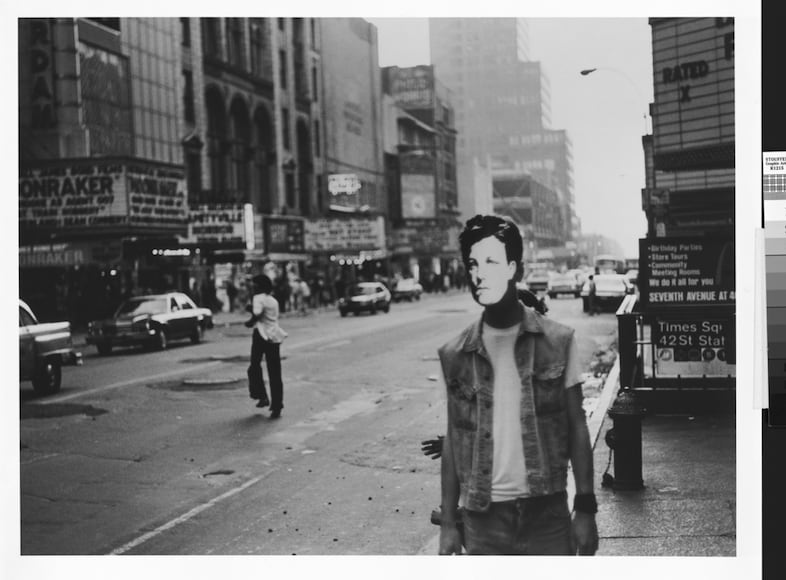

Rimbaud loomed over the artistic counterculture that Wojnarowicz was part of, and here he becomes a ghostly collaborator. Wojnarowicz places the afterimage of Rimbaud in diners, hotels, and amid the rubble of the city, evoking him like a graffiti artist’s signature; graffiti, and political intervention through public work defined much of Wojnarowicz’s practice as a visual artist, and by bringing Rimbaud into his visual language, he creates not only an artistic kinship between himself and the poet, but asks if it’s possible for the world – whether it’s the landscape of Rimbaud’s Paris compared to a New York City on the verge of a seismic change; the possibilities of the art world; or the silence of political institutions – to change. There’s a tension in this work, as Wojnarowicz considers the differences between what was and what’s yet to come.

In a new publication exploring the history and legacy of the photos, and an ongoing exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, Marguerite Van Cook emphasises the tensions that exist within the photos, the vanishing distance between the French poet and the American artist. She writes, “Wojnarowicz, the symbolist, creates allusive connections in which pleasure, sexuality and beauty overcome the grey realism of the world of the image.” Rimbaud’s eternally youthful, rebellious face seems to offer at once an escape from the derelict buildings and crowded subway trains that Wojnarowicz captures, and a sign of just what the world can do to a figure like Rimbaud, and those who have come in his wake.

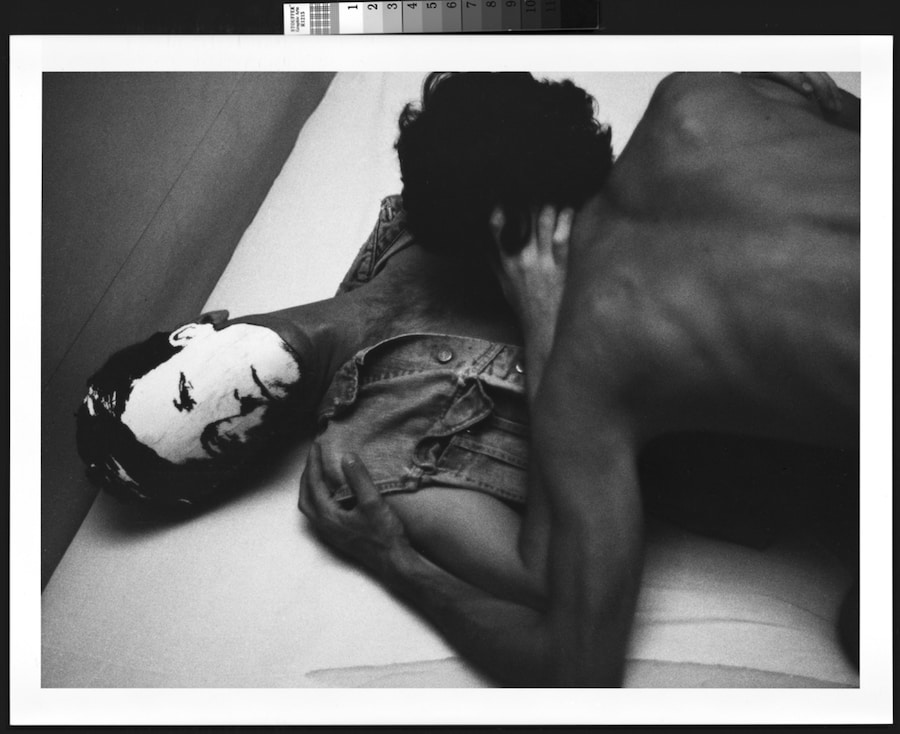

In diners and on subway platforms, there’s something uncanny about the mask that Wojnarowicz’s collaborators wear; it seems too well-defined and clean compared to the surrounding world, like something ripped from another time, what we might think of now as a glitch. It seems brighter than the city, a guiding light, or promise of something to come. Some of the most famous images in this series are the most dejected: Rimbaud with a needle in his arm; Rimbaud lying on a floor mattress in an empty apartment building, the city standing by in an eternal, uncaring vigil outside the window. The curator of the Leslie-Lohmann exhibition, Antonio Sergio Bessa, wonders if Rimbaud’s “image of modernity was dystopic”, in the poet’s A Season in Hell, where Rimbaud seems to be raging against the world, desperate to transcend it. In The Alchemy of the Word from A Season in Hell, Rimbaud yearns for something beyond the changing nature of the world: “You must set yourself free / From the striving of Man / And the applause of the World! / You must fly as you can …”

It’s no surprise, then, that Wojnarowicz would find a kindred spirit in Rimbaud. Both were teenage vagabonds, with Wojnarowicz separating from his dysfunctional family and living on the streets by the time he was 17 (coincidentally, the same age as Rimbaud in the Carjat portrait). By placing the mask of Rimbaud across the city that he spent years roaming, Wojnarowicz gestures towards a lineage between the two men. In the essay Our Rimbaud Mask, Anna Vitale stresses that “this Rimbaud is not our Rimbaud”, and could only ever belong to Wojnarowicz. The same could be said of the city that looms over these photos in the background; that this is Wojnarowicz’s portrait of New York as much as it is a portrait of Rimbaud.

Over a decade after creating the Rimbaud in New York series, Wojnarowicz would write in Post Cards from America: X-Rays From Hell that the discovery of his HIV diagnosis would underline something he already understood: “not just the disease, but the sense of death in the American landscape.” A sense of death that Rimbaud seems to capture in his paintings, and that Wojnarowicz also sees reflected back at him in the Rimbaud in New York series. There are times when these photographs seem haunted; not just by the image of Rimbaud, brought forward by almost a century, but by the march of time, and the shadow of death that it might also represent.

There’s one image in Rimbaud in New York where the mask isn’t being worn. Instead, Wojnarowicz photographs it on the street, isolated and discarded. Rimbaud had always been an outsider, the mask a shorthand for that very notion within the art scene where Wojnarowicz developed his craft. This group of artists, given sideways glances by art world institutions and, with the arrival of the Aids crisis, the wider government, were always in danger of being cast aside. So too, Wojnarowicz seems to tell us, is Rimbaud. And still his face lingers, a ghostly palimpsest over the top of the artist and his collaborators. Van Cook argues that Wojnarowicz’s use of Rimbaud’s image shows a simultaneous “scorn for the art establishment, and the call for a new creative imagination”. And still, he seems to show us just how difficult that can be; how stark and severe the surrounding world can be, and the ease with which someone could be discarded.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York is on show at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York until 18 January 2026.