From 1979 to 1990, Zofia Rydet set out to photograph the inside of ‘every’ Polish household, capturing rich personal histories and lives in challenging flux

In a new show at The Photographers’ Gallery dedicated to a documentary project numbering over 20,000 photographs, one of the most indelible images impressed on the visitor isn’t a photograph at all. In a film which loops in the show’s last room, we see a stooped, elderly woman in a white blazer, trudging through the countryside, camera bag looped over one shoulder pad. That’s Zofia Rydet, sometime in the late 1980s, looking for houses to enter and people to photograph inside them.

In the retrospective of the Polish photographer and her Sociological Record project currently on view at the London institution, we gain a sense of Rydet’s tenaciousness not only through Andrzej Różycki’s documentary film, but through the sheer ambition of her series of Polish domestic life spanning 1979 until 1990. She was already 67 by the time she began her mission: to photograph the inside of ‘every’ Polish household.

“These are interiors of people that were not very photographed, and probably didn’t even own cameras,” says Clare Grafik, co-curator of the show alongside Karol Hordziej. “She became very interested in all these tiny details that really start to paint a picture about the inhabitants of these houses and what they came to symbolise about the person that lived there.” This is the first time the monumental series has been brought to the UK. One organising principle among the displays are the different categories and connectives that Rydet herself identified in her ongoing project – such as Women on Doorsteps, Windows, Door Signs, and, thanks to the country’s Catholic nature, a special series dedicated to the preponderance of framed iconography of Polish Pope John Paul II’s image around the house, which seem to haunt every nook and cranny.

When I mention to co-curator Hordziej that such images reminded me strongly of the rural Irish homes of my relatives, he notes that such projections are really part of the magic of encountering Rydet’s work. “For us, the intuitive idea is that this is very Polish,” he says. “But when you bring this work to a new context, even for myself, I start to look at them differently. But wherever we show it. People always see things familiar to them.”

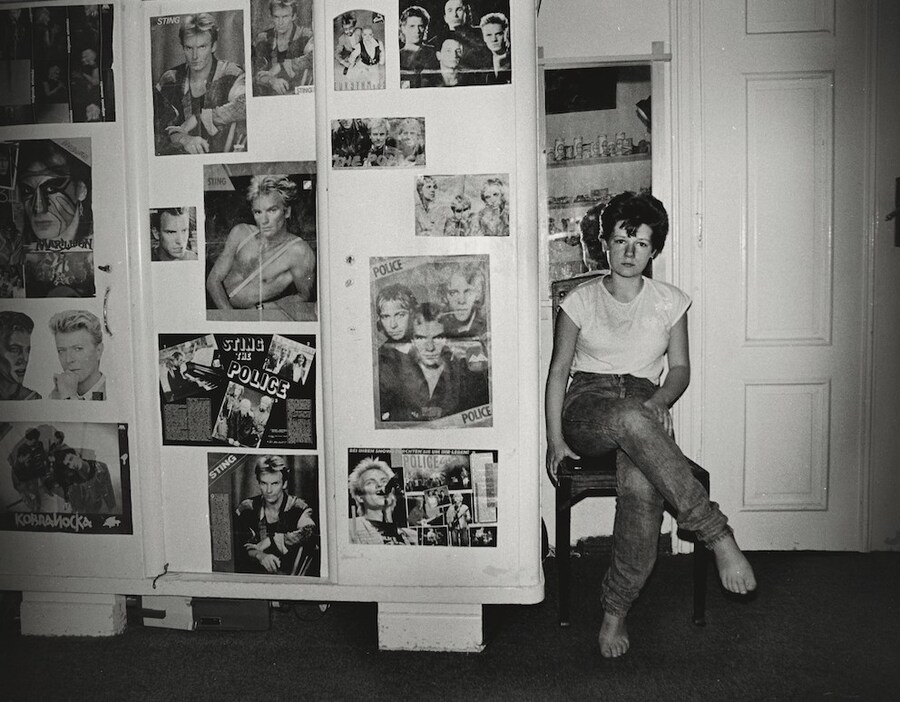

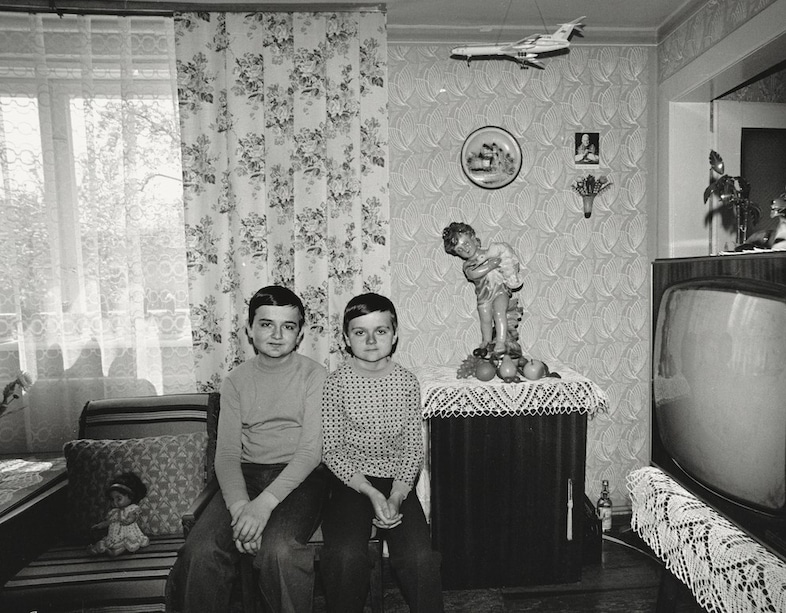

Still, the photographs are equally in tension with such categorisations, and it’s when the portraits of individuals in their homes are displayed without comment – a punk teenage girl with walls covered in posters of Police-era Sting and David Bowie; brothers, perhaps twins, who seem miniscule among the doilied surfaces and large cathode television that seems to overwhelm them – that the real power of Rydet’s project comes into play. As the crowded display of photographs triangulates with the crowded objects in the homes of the subjects – beds constantly jut up against kitchen tables, picture frames threaten to fall, and people appear too large for the seats they perch on – a sense of rich personal history, but also lives in challenging flux, emerges.

Rydet herself experienced the scarring upheaval of her era: she had undergone a brutal Nazi occupation in her home city of Stanisławów, and had essentially left when that part of Poland has ceased to exist. “It’s very common for this generation not to talk too much about the past,” says Karol, but, as Grafik adds, the photographs themselves may have been a way to get back some of the things she had lost. “She recognised in these rural settings a similar folk culture from earlier on in her life, and this was her way of trying to somehow get that back. That’s part of how it became so obsessive for her: she saw it disappearing, and she really felt she suddenly had this opportunity to keep hold of it.”

In the documentary in the show’s final room, we see Rydet characteristically enter a countryside cottage, unannounced, to take someone’s photograph. “Good morning sir!” she says to the old man inside, and proceeds to gently spar with him about taking his photo. “I don’t know if I give you my consent,” he jokes. To which his photographer says, “You are so beautiful, you have to agree.”

Zofia Rydet: Sociological Record is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London until 22 February 2025. Zofia Rydet: Sociological Record is part of the UK/Poland Season 2025. It is produced by The Photographers’ Gallery in partnership with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute (co-financed by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage), Poland, and the Zofia Rydet Foundation.