The artist’s new show transforms the Serpentine into a ‘listening space’, with around 300 records from his personal collection serving as a backdrop to paintings shaped by his life in Trinidad

“It’s always puzzling to visit the homes of extremely sophisticated contemporary artists (or collectors), and discover that their taste in music consists of uninformed wank,” wrote Neel Brown in Frieze in 1998. He was reviewing Blizzard Seventy-Seven, Peter Doig’s first institutional survey at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, for which curator Matthew Higgs had appended a catalogue of the artist’s record collection for the show’s publication.

At the time, Doig was breaking through as a painter: shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1994, and exhibiting with Victoria Miro in London and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York. His slow, atmospheric paintings of remembered places – from the snowscapes of his Canadian upbringing to his ‘Concrete Cabin’ paintings of Le Corbusier’s modernist housing complex in Briey – stood apart from the theatrics of the YBAs, placing him outside the prevailing currents of the decade.

“But Doig’s taste is not wank,” Brown concluded. “It’s a medium-cool collection – no MOR, Marks-and-Spencer rock like U2 or Sting, but an eclectic mix of classic and left-field rock with a high percentage of indie.” The catalogue listed Doig’s cassettes, compact discs, 12-inch vinyl and 7-inch singles in full, exposing an aesthetic sensibility that, as Brown put it, “makes vulnerable and securely bonds the compiler within the safe codes of a sub-group.” That sensibility mixed funk (James Brown), rock (Neil Young), reggae (Toots and the Maytals), with hip-hop (Wu-Tang Clan), soul (Aretha Franklin), and Kraftwerk – the German electronic band Doig came to know during his years in Düsseldorf, where he held a professorship at the Kunstakademie between 2004 and 2017. In fact, their track Computer Love (1981) would later make it onto his Desert Island Discs selection, alongside Aretha Franklin’s Jump to It (1982), chosen in tribute to his club-going youth (although he admits he could have picked any number of her tracks).

On the back cover of Kraftwerk’s 1973 studio album Ralf & Florian, the founding duo, Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, sit surrounded by hulking old cinema speakers. “The cinema sound systems, like those made by Western Electric in America and Klangfilm in Germany, were designed to fill huge halls, so they use low amplification but have a big, warm sound,” Doig told Michael Bracewell in a 2025 interview. He first heard about these speakers through friends, and later began tracking down similar ones for StudioFilmClub, the weekly cinema he ran with artist Che Lovelace in a former rum factory in Port of Spain, Trinidad. “I started off with a basic little projector on a table with two borrowed speakers hooked up to it,” Doig said. “But as the club became more popular, I decided I wanted to make it a bit more unique – to have better sound and visuals.” Soon he was scouring disused cinemas in the capital, salvaging a massive Altec speaker that became the foundation of the cinema’s new sound system. Later, in Düsseldorf, his connection to Schneider allowed him to expand the collection. And when the project demanded a technical whizz, in came Laurence Passera, a London-based restorer and cinematic sound system enthusiast with whom Doig has collaborated on House of Music, his new exhibition at the Serpentine South Gallery in London.

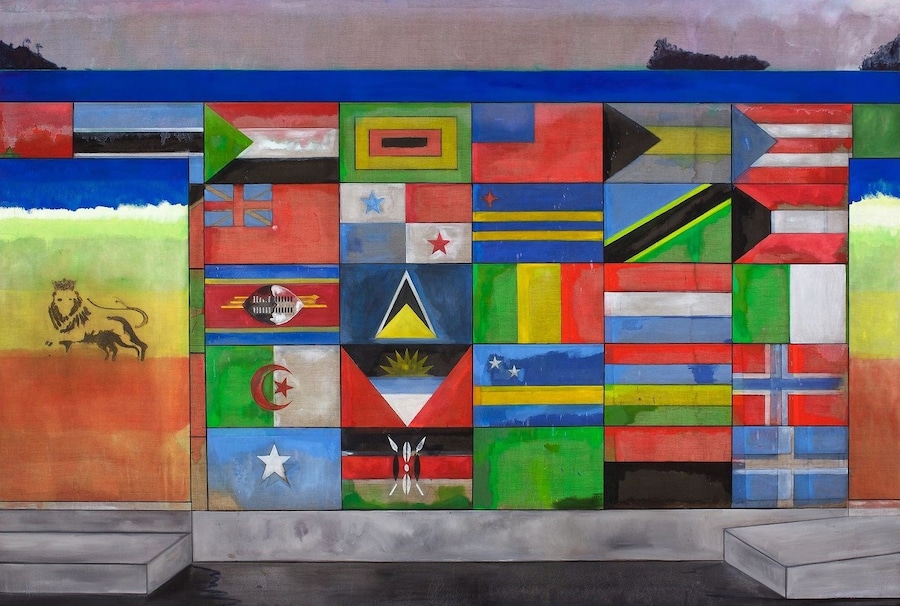

The new show sees Doig transform the Serpentine into a ‘listening space’; the first time the artist has integrated sound into his work. The walls carry paintings long shaped by his life in Trinidad, the Caribbean island Doig moved to as a child from Scotland, and has spent much of his life in since. Among them is Lion in the Road (2015), part of a recurring motif from the lion’s ubiquity in Trinidad and its Rastafarian link to the Biblical Lion of Judah. Figures from the island appear too, notably Shadow, seen in Music Shop (2018) and in Shadow (2019), a portrait of the calypsonian musician in his skeleton suit. The lyrics from Shadow’s 1978 song Dat Soca Boca is where the exhibition takes its title. Music comes in elsewhere as well; in Maracas (2002–2008) with its tower of audio speakers, part of a body of work that Doig began after his first trip back to Trinidad in 2000, inspired by the architectural stacks of loudspeakers you see set up throughout the island’s landscape.

Two Western Electric / Bell Labs sound systems (otherwise known as the “great grandfathers” of modern ‘high end’ audio), sit in the middle of the gallery. Doig has selected about 300 records from his collection for the gallery’s staff to play on rotation, so the space is never without music. On Sundays, Sound Service invites musicians, artists, and collectors including Nihal El Aasar, Ed Ruscha, and Samuel Strang to share tracks from their own collections, while evening sessions see guests like Lizzi Bougatsos, Dennis Bovell, and Brian Eno respond to one another’s tracks and samples in front of a live audience. To stand in the exhibition is to step into Doig’s world, where music and painting are inseparable, one amplifying the other. “I can’t work without it,” Doig says. “Impossible.”

House of Music by Peter Doig is on show at Serpentine South Gallery in London until 8 February 2026.