Photographer Andrew Maclear shares unseen imagery from the decadent London shoot of Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s cult 1970 film Performance

Swinging London arrived in the mid-1960s, taking the world by storm with its inimitable blend of sex, frocks, and rock and roll. “It was the post-war period in England when everything came back to life and suddenly had a different energy primarily expressed through music. Music was the great driver,” says documentary filmmaker and screenwriter Andrew Maclear.

Maclear left school at 15 and landed in London, getting his start as a bicycle messenger for a film company in 1966. He worked his way up to cutting room trainee, only to be let go. Set adrift, his father gave him a camera, which led the young lad down an unlikely path filled with counterculture icons like John Lennon, Allen Ginsberg, Francoise Hardy, Jimi Hendrix and Jean-Luc Godard. “They were all perfectly accessible,” Maclear says. “If there was an event going on, you could knock on a dressing room door and the artist would open it themselves. I remember going to photograph The Who, and when Keith Moon opened the door, I said, ‘I want to do some pictures,’ and he said, ‘Come on in.’”

Looking back, Maclear remembers a simpler time filled with possibility and hope. “It didn’t last long, but from ’65 to ’70, the mood in London was marvelous – open, free, optimistic,” he says. “I remember when the Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album came out [in 1967], there was nobody in the street, because everybody was in their houses listening to this album. That’s how powerful the music was.”

But there was another, equal if not opposite power, coming up from the London underground. Gangsters like the Kray Twins were a fixture on the nightlife scene, modelling their outfit, The Firm, after Al Capone. “They were the best years of our lives,” Ronnie Kray wrote in his 1993 memoir, My Story. “The Beatles and the Rolling Stones were rulers of pop music, Carnaby Street ruled the fashion world ... and me and my brother ruled London. We were fucking untouchable.” That is until 1968, when Scotland Yard shut down their outfit.

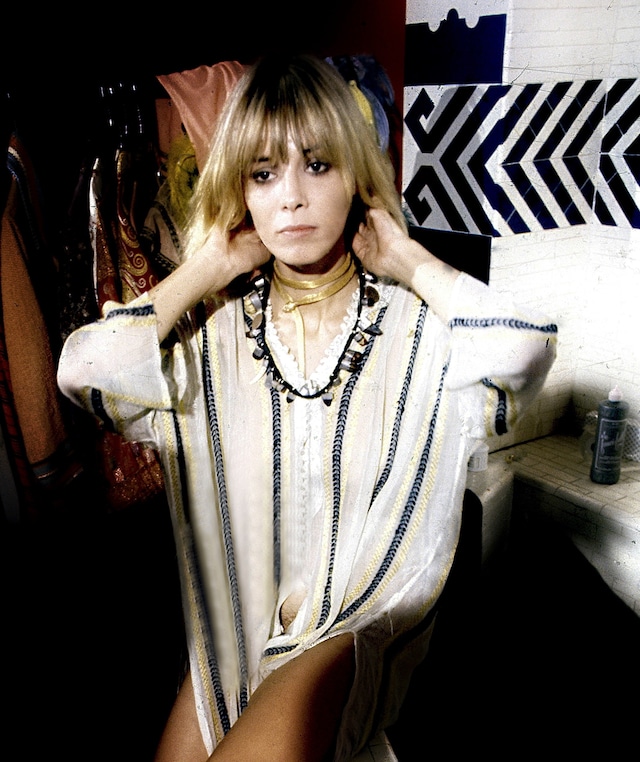

That very year, directors Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg were filming Performance, a British crime drama about Chas (James Fox), an East London enforcer hiding out in the home of a reclusive rock star, Turner (Mick Jagger). The experimental film unfolds like a fever dream, with hallucinatory sequences of drugs, sex and violence that set executives at Warner Brothers studio on edge. They financed the film thinking it would be a madcap musical along the lines of the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night, betting the house on a Rolling Stones soundtrack that never came to pass as Anita Pallenberg, Keith Richards’ then-girlfriend, took the role of Turner’s bisexual girlfriend Pherber. Jagger and Pallenberg cavorted and canoodled throughout the film, often naked in bed and in the tub, joined by Lucy (Michèle Breton), with rumours of real sex during filming later confirmed by Rolling Stones co-founder Ian Stewart.

As fate would have it, Maclear’s brother Robin was a crowd artist on Hollywood films, and was working as a lighting stand-in for James Fox on Performance. “After he’d been there for two or three days, he said, ‘You should come down here, because this is a really weird film,’” Maclear remembers. “They rented a splendid and very conservative London townhouse down in Knightsbridge and sent the owners away, to the Bahamas, I think, for three months. They promised to leave it the way it was, which they didn’t. The door, which was on the street, was always open and people were coming and going all day long.”

Robin asked if his younger brother, Andrew, then 17, might visit the set. “They said, of course, so I walked in and I just stayed there,” he says. “I kept going every day, and I would stay there all day. At the end of each shot, they called, ‘Where’s Andrew?’, brought me into the room and said, ‘You can have four or five minutes’ – and Mick and Anita would be in bed with Michèle Breton.” Maclear said little as he photographed the scene, never disrupting the glittering web of bohemian beauty, desire and fantasy.

“I was not a professional photographer, and I never regarded myself as one,” he says. “I didn't ask them to do anything. They would be in the bed talking to each other, and now and again, they’d look in the camera. I would say, just give me your eyes for a minute. And then I would leave. I was there for about a week and finally somebody said, ‘Well, who is this guy?’” The question came the day after Maclear accidentally stepped on Jagger’s ankle while standing on the bed, angling for a different view of the scene. And with that, the serendipitous encounter came to a close. But the photographs, like the film, live on in Performance: The Making of a Classic (Coattail Publications).

Studio executives never really got a handle on the film, shelving it for two years, trying different edits but never getting a fix, before releasing them varied and sundry in 1970. Critics were wildly underwhelmed if not outright appalled, but their disparaging remarks did nothing to stop Performance from rising to become what is now recognised as a classic of British cinema. The open and experimental landscape of the film drew luminaries like Cecil Beaton, who also photographed the film set. “There are many eminent photographers who came up from that period and are still working today,” Maclear says. “I wasn’t one of them. I was an accidental photographer.”