One of the joys of a retrospective is finding artworks that were never destined for the spotlight, instead remaining buried in the archive. On view at Tate Britain’s new Lee Miller exhibition is a pair of near-identical photographs, each no bigger than an iPod Nano, depicting a severed breast laid out on a plate, flanked by a knife and fork. They were dated from around 1930, when a young Miller had been working as Man Ray’s apprentice in Paris. In need of some extra money, she began photographing surgeries at the Sorbonne Medical School and, after witnessing one radical mastectomy, asked the surgeon if she could take the removed breast back to her studio at French Vogue. She had apparently seasoned it with salt and pepper for the photograph, before Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Michel de Brunhoff, in a fit of disgust, threw both Lee and the breast out. Absurd, if a little gross, these tiny two photographs have been pulled from the archives for the first time in a retrospective of 230 odd works that chart the restless, shape-shifting life of the photographer Lee Miller.

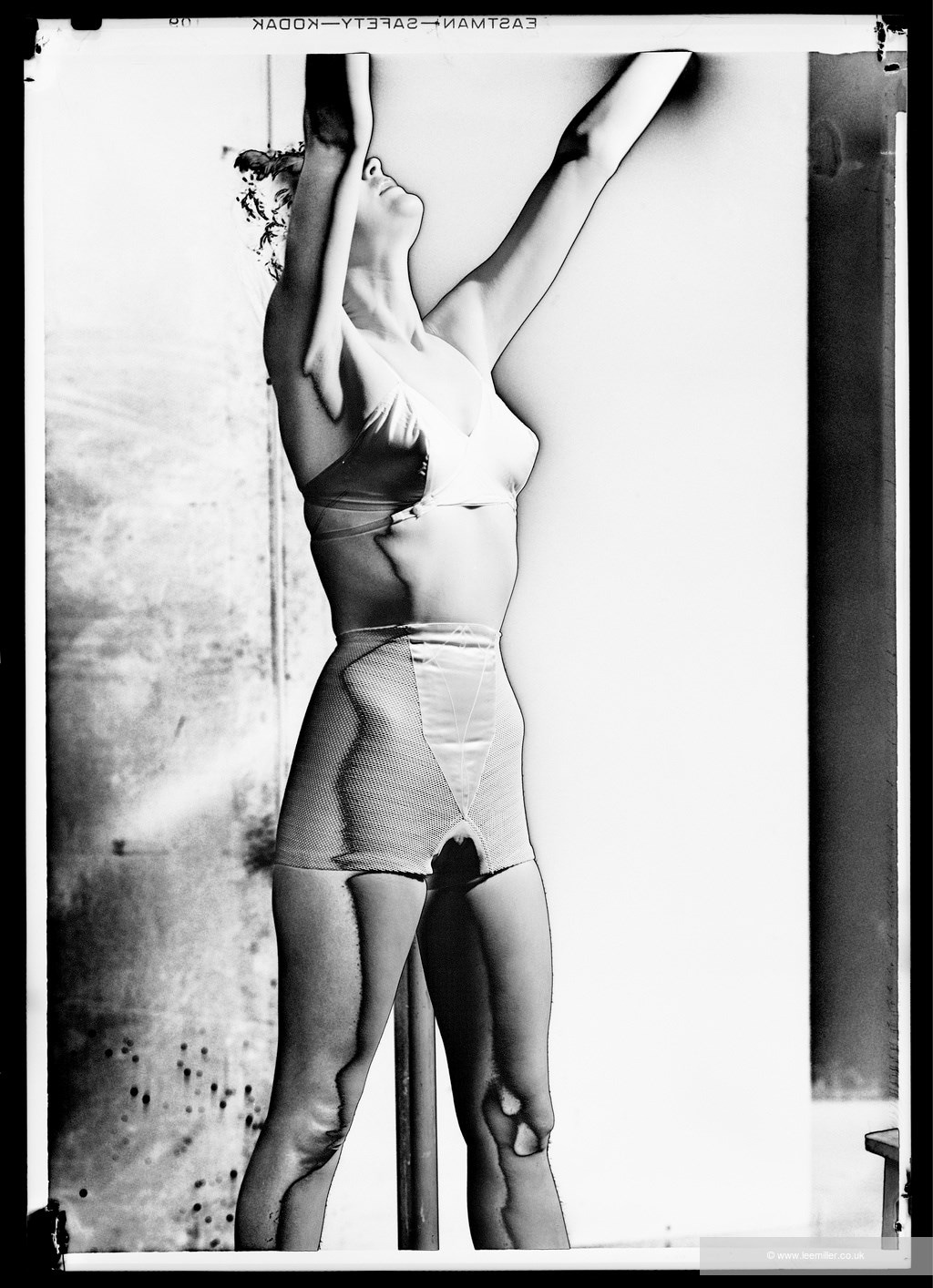

By the time those photographs were taken, Miller was already moving through the male-dominated circles of surrealism in Paris, working at Man Ray’s studio, first as a model, then as his apprentice and collaborator. Born in 1907 in Poughkeepsie, New York, she’d started in front of the lens as a Vogue cover model after being rescued from an oncoming car on a Manhattan street by the publisher Condé Nast himself. But it was in Paris, and in Man Ray’s dark room, that she learned to bend photography to her own imagination. She went on to open her own studio, first in Paris and then in New York, before marrying Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey in 1934 and moving to Cairo.

Restlessness (and a love affair with the artist Roland Penrose) eventually drew her to London on the eve of the second world war, where she worked for British Vogue (her dispatches from Saint-Malo, Luxembourg, Dachau and Buchenwald turned the magazine’s glossy pages into eyewitness testimony of war as it was lived out). That trajectory, from the studios of Paris and New York to wartime London and a final landing in East Sussex, anchors the retrospective, which gathers work from every iteration of a life sustained by adventure and, perhaps above all, an aversion to routine. As her son Antony Penrose put it, “For Lee, travelling was always more important than arriving.”

As with the Paris breast studies, a room of photographs she took while living in Egypt reminds you how much of Miller’s work, until now, has slipped from view. To fend off the boredom creeping into her life there (“I sit around and read rotten detective stories instead of writing to you,” she wrote to her brother Erik in one letter dated 1935), she began organising excursions into the desert; travelling to the monasteries of Saint Antonius and Saint Paul on the Red Sea hinterland. Those trips pulled her back to the camera – something she had a habit of abandoning, only then to fall back in love with.

One of the best known works from this period is Portrait of Space Al Bulyaweb, near Siwa, Egypt (1937), taken inside a remote traveller’s rest stop en route to Siwa in Egypt’s Western Desert. The torn mesh in the foreground opens onto a barren, rocky plateau beyond; the image reads as both an expression of isolation and, perhaps, a longing to break out of it. Elsewhere, her surrealist eye roams the landscape, coaxing the strange out of the ordinary. The domes of the Deir El-Soriani Monastery in Wadi Natrun swell into the curving female forms of her Man Ray days; sand ripples shot at a skewed angle resemble the abstract wobbles of a Gerhard Richter painting; and in Cock Rock, taken near Siwa in 1939, a boulder reveals, on second glance, a positively phallic shape.

And then there’s Miller’s writing, a side to the job she supposedly loathed. There are tales of Lee hunched over her Hermès Baby portable typewriter, wailing in despair, to be found the next morning asleep on the kitchen floor surrounded by empty bottles of cognac and a sea of balled-up copy. “I lose my friends and my complexion in my devotion to the rites of flagellating a typewriter,” she confessed to Audrey Withers, her editor at British Vogue, who, while a safe distance from any front line, found herself in Lee’s firing line on more than a few occasions. And yet, when she did wrestle the words out, they came with the same ferocity and clarity as her photographs.

These first-person dispatches – many laid out in glass vitrines throughout the exhibition – show not only the rawness and urgency of someone witnessing history at its most grotesque, but flashes of the dry, descriptive wit that one imagines lit up the dinner parties at Le Cyrano in Montmartre, the Parisian restaurant turned surrealist lair of her earlier years. In one piece from the Alsace Campaign, published in Vogue in April 1945, she writes: “The silence was our deafness from the clanking, grinding roar of a French armoured division, anachronistic and as shocking as a moustache on the Mona Lisa.” Nearby, a photograph by Lee of a soldier leaning against a tower of logs is captioned: “Pleased as punch with the lace curtains that camouflage his tank destroyer against the snow.” And given the stories of Lee securing scoops by dropping a few liquor bottles at the feet of the opposition – most famously to get that photograph of her bathing in Hitler’s tub – it wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine she sourced the drapery for him herself.

And of course, that extraordinary photograph is here too: Miller bathing in Hitler’s tub in his abandoned Munich apartment; an image that would come to stand as a darkly fitting metaphor for the war’s end, taken on the same day Hitler and Eva Braun killed themselves in a Berlin bunker. It appears alongside a harrowing roomful of her photographs from Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps, taken just weeks after their liberation in 1945. There’s the caved-in face of an SS guard, a train packed with corpses, two Allied soldiers peering in, and a cropped image of a pair of legs – a survivor – clad in the striped uniforms forced on prisoners. Standing in front of these photographs, you feel a world away from the Man Ray studio experiments and glossy Vogue couture of her early rolls of film. And yet, the same fearlessness is there; the instinct to cross whatever frontier she had to in order to reveal what others simply couldn’t see. Miller’s surrealist eye from those early days never left; she simply carried it to the darkest edge of reality, so others were made to see it too.

Lee Miller is on show at Tate Britain in London until 15 February 2026.