As the artist’s new show opens in Brussels, her daughter-in-law Ginny Neel reflects on how these paintings reveal her evolving inner world

A dead fish lies still on a chopping board, its rear end sliced off, scales scattered across the wood. One animated eye and open mouth make it look as though it might slither off the table. This is Alice Neel’s Fish Still Life (1950), a small, ghostly painting that is currently on show in Still Lifes and Street Scenes, a new exhibition at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels. It is one of numerous works that demonstrate quite how adept the US artist was at capturing deep emotion and existential angst, mostly without the impact of human sitters. Together, these works offer a thoughtful view of Neel’s evolving inner world.

The exhibition opens with Harlem River (1928), a haunting view of a boat traversing the city water against a turbulent sky. It was painted the year after Neel’s daughter Santillana died of diphtheria. “There’s almost a weeping river, the boat is collapsing, the grey of the clouds, the buildings almost falling into the river ... She put her emotions in the imagery,” says Ginny Neel, the artist’s daughter-in-law, who runs the estate with Hartley, the artist’s son. While Neel didn’t offer in-depth reasoning for individual works, she did keep diaries in the form of written notes on paper. At the time the work was made, the artist expressed a panic around money, believing the lack of coal for warming the apartment led to Santillana’s early death. “All these feelings of guilt and sadness filled her. And I feel that all that sadness was transferred into the painting.”

As the show moves through the decades, Neel’s changing emotional landscape is palpable. Paintings from the 1940s and 50s contain a foreboding tension that might be read as the lingering undercurrents of grief or the ripples of the second world war. Her interiors are drenched in long shadows, thick paint depicting items on the cusp between life and death, from the troubled fish to a series of cut flowers. The 60s emerge as a ray of sunshine, featuring expansive street scenes and leafy suburban neighbourhoods, brought to life with expressively long streaks of rain, distant figures splashing in puddles, and thick snow.

By the 60s, Ginny notes, both Neel’s sons had grown up and were independent. “She didn’t have the worries of parenting, also her partnership with Sam Brody had ended. She did not have to worry about money, she was able to function as an artist. The women’s movement helped her work be seen. Everything in her life became less stressful.” Neel’s scenes became more experimental, with pared back, almost abstract backgrounds surrounding more naturalistically depicted subjects, as in Joe Stefanelli (1963). “She had always been confident, but now there’s confidence not just in the line, but in how far she goes in presenting what she needs to in the painting,” says Ginny of this time.

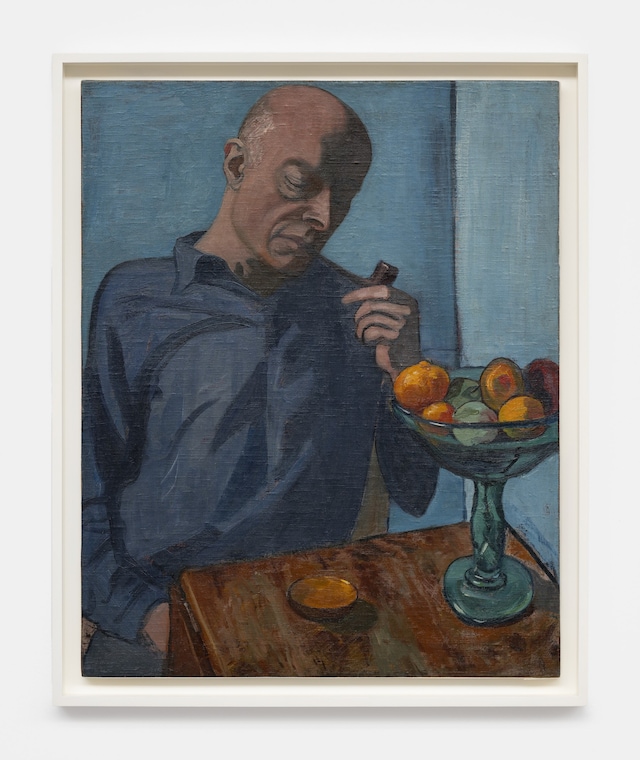

The show includes numerous lesser-known paintings, some of which are mainstays within the family collection. John with Bowl of Fruit (1949) retains the calm of a still life despite the presence of John Rothschild, a businessman who was friends with the artist and a recurring sitter. The painting has been in Ginny and Hartley’s home for some time. “It showed both the strength of her figure and the strength of a still life,” says Ginny. “They’re equal in intensity. She would not ever have placed him next to that bowl. He would have sat there and the bowl would have been there and she saw the intensity of the colours and the beauty of the pairing and then gone from there.”

Ginny is keen to express that the artist was not interested in directly symbolic or overly contrived works. Neel worked intuitively, knowing the minute she saw something that she wanted to paint it. “She wasn’t looking for it, but then once she painted it, part of what had excited her about the image was how it made her feel. And so that feeling would be in the image she painted … She could be full of joy and walk into a room and see a wilted flower, and suddenly want to paint it and feel the sadness of it.”

Mortality is confronted in the final room, which is dominated by The Living and the Dead (1981), a sparse painting that features a large skull in the foreground, with roughly sketched human figures in the background and a surrounding blank page with the faint outline of a window. “She was starting to have blackouts,” says Ginny. “The New York doctors thought that she had a neurological condition and she started taking a lot of pills for it and so on, and she thought, of course, she might die. Hartley took her to Boston and then found that she needed a pacemaker because her heart was stopping. It saved her, but she was aware that she might die at any time.” Hartley highlights the intrigue that Neel brought to even the heaviest of life’s moments. “She wasn’t scared of dying,” he considers. “She just didn’t want to miss anything.”

Alice Neel: Still Lifes and Street Scenes is on show at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels until 22 November 2025.