Alejandro González Iñárritu’s new installation at Fondazione Prada uses unseen footage from his cult film, Amores Perros

“How many films can exist within a film?” This is the question lying at the heart of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s celluloid installation at Fondazione Prada. In the making of his cult cinematic masterpiece Amores Perros (2000), Iñárritu shot over a million feet of film, yet used only 15,000 feet in the composition of his tense, enthralling tale of three individuals in Mexico City whose lives collide when a car crash randomly and violently brings them into each other’s paths.

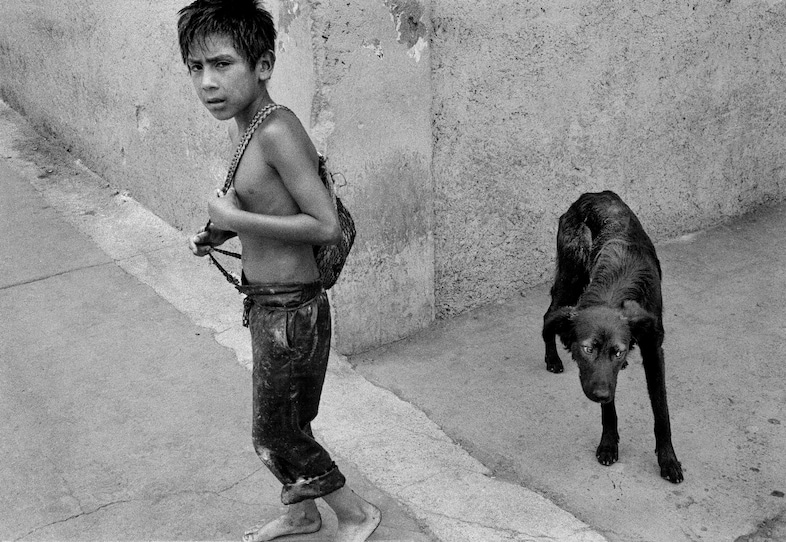

The triptych of stories in Amores Perros follows a young man (Gael García Bernal) from the slums who’s become embroiled in the brutal business of illegal dog fights, a model who’s just signed a lucrative contract, and an enigmatic hitman. Over the past seven years, Iñárritu has been combing through the leftover 35mm film, which has been in storage at the National Autonomous University of Mexico for 25 years, to salvage the many other precious narratives and “ghosts of celluloid” embedded in the remaining 16 million still frames.

What emerges in his new installation, Sueño Perro, is a series of vignettes fraught with grit, suspense, lust and brutality. Unburdened by the task of piecing together a storyline, Iñárritu was free to appraise the excess footage with a fresh perspective. Speaking at the show’s opening, the director explained, “I was able to observe the material flowing freely with no narrative attached, and I was very attracted by things that I had not seen at that time, appreciating sequences that never made it and seeing that they were very rich in a different way, serving a completely different exercise of image, sound and memory.”

Moving through the vast, dark gallery spaces in Fondazione Prada, each hosts one or more colossal projectors casting out Iñárritu’s new configurations of footage. You may recognise the characters and settings from Amores Perros, but you’ve never seen these unseen sequences before, enriching the film’s universe while existing in their own right as self-contained micro-narratives.

For anyone already familiar with Amores Perros, there’s something uncanny about the exhibition. Iñárritu says, “Looking at these images was like a dream, like when you dream about people that you know, but they are not in the right place, or they are not as you remember. It’s like seeing something very familiar, but you haven’t seen it before. I would like to invite you into this dream of light; a labyrinth of light permeated by the sound of Mexico City.”

Sueño Perro is a visceral constellation of traffic collisions, dogfights, loaded exchanges, street life, sirens, shouting, barking and phone calls. “I wanted to make a very sensorial physical experience. There’s no order, there’s no right or wrong. I want people to explore the spaces and make their own narrative by visiting the rooms in a different order,” the director explains. “We cannot underestimate the power of 35mm. In the age we’re living in, everything is digital, and pixels have dehumanised the way we see things. 35mm is much closer to the way we see and experience life. To see these machines projecting beams of light, as cinema was invented, is incredibly beautiful. I would like people to feel the physicality of it.”

Amores Perros is a story about the febrile streets of Mexico City at the turn of the millennium. On the first floor of the foundation, Mexico 2000: The Moment that Exploded is an exhibition and soundscape by Mexican writer Juan Villoro, which adds additional layers of meaning and context to Sueño Perro and this seminal time in the city’s history. In a statement about the show, Villoro explained, “Amores Perros can be located at a precise historical juncture. In the canonical year of 2000, Mexico was experiencing a rare moment of long-awaited hope: after 71 years in power, the Institutional Revolutionary Party had finally lost a presidential election, and the country was preparing to discover genuine democracy. At the same time, reality presented a panorama of inequality, corruption and violence.”

Despite being shot two and a half decades ago, the “ghost material’ in Sueño Perro feels vividly alive. Mexico 2000: The Moment that Exploded traces the political, social, economic and religious landscape from which the interwoven stories in Amores Perros were shaped. Considering the prescience of Iñárritu’s celebrated debut, Villoro says, “Filmed at a ‘moment of change’, Amores Perros did not reflect the end of an era but rather the beginning of a downfall. Twenty-five years later, its social relevance is alarming: what was happening then is still happening now. Its explosion is still ongoing.”

Sueño Perro: Instalación Celuloide de Alejandro G. Iñárritu is on show at the Fondazione Prada in Milan until 26 February 2025.