Three decades on, Sophy Rickett looks back at her rebellious portraits of women publicly urinating in London’s zones of power

A young woman, captured in black and white, dressed in corporate attire with slick bobbed hair, is standing on Vauxhall Bridge at night. She’s lifting up the front of her skirt and she’s urinating against the pillar – not squatting, but standing and pissing like a man, gazing with rapt intent at the arc of urine soaking the pavement at her sober Mary Jane heels. This kind of pissing is a profoundly machismo gesture, at odds with the demurely dressed figure. It signals the marking of territory. It’s carnal, feral, aggressive, distinctly unfeminine. It’s an image from Sophy Rickett’s seminal, arresting photo series Pissing Women, currently on display in the exhibition Stream at London’s Cob Gallery. Once you’ve seen it, you’ll never forget it.

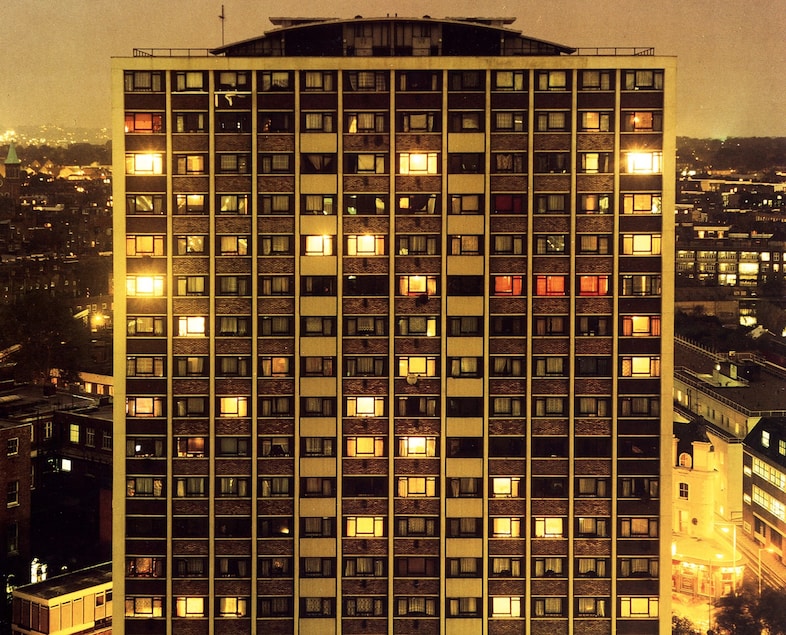

The series was born in 1995, when the art school graduate found herself taking on temp work at the Financial Times, whose offices had floor-to-ceiling windows and views of St Paul’s Cathedral and the City across the river. Initially, she was uninterested in her new workplace, but she gradually became aware of having crossed one of London’s many invisible thresholds into a world she hadn’t ventured into before. It captured her imagination.

London contains worlds within worlds, an accumulation of overlapping territories demarcated by invisible borders and boundaries. Different communities move through the same shared space with varying levels of access and privilege; certain groups and activities are permissible in one part of town while they’re less tolerated in another. It’s a complicated, nuanced and ever-shifting socioeconomic cartography. As the capital’s financial epicentre, the City is its own small but powerful planet with a distinct ecosystem of rules and hierarchies. “I began to recognise it as a culture in its own right, with its codes, systems, conventions, communities and aesthetics,” Rickett tells AnOther. “Rather than rejecting it, I started to engage with it on my own terms, considering it as a context in which I could make work. Reimagining the building as a location, with its cultural and spatial resonances, led me to understand my own position – even as a temporary worker – as being somewhere between compliance and subversion.”

Against this landscape of corporate, surveilled London, Rickett began conceiving of art projects that would acknowledge her own “own complicity within the system” while also being an act of defiance against the mores and power imbalances of the financial industry. More immediately, she also wanted to transform her day job into something meaningful and creative.

“At art school, I probably would have said [the guiding principle of Pissing Women was] something about exposing and destabilising codes of behaviour that have such a conditioning and disciplining effect on women in public space, especially in corporate environments,” she reflects. “But at the time, it was more about articulating my own experience as a recent graduate, encountering the world of corporate finance and news media at such close proximity. It was like a reckoning with the reality of my day job – trying to make it creatively productive, not just financially so. To be ‘feminine’ is to be disciplined, restrained. I wanted to see what happened when those boundaries were tested.”

Stream brings together the work of Sophy Rickett and her collaborator Rut Blees Luxemburg. Thirty years have passed since Rickett enacted these urinary interventions, shot after nightfall in the proximity of MI6 and across the City of London’s grand porticos, but the sight of women – especially women dressed in conventional corporate attire – performing these acts of public urination still retains its power to shock.

“Public urination is so strongly coded as a male behaviour that when women do it, even in relatively permissive contexts like Glastonbury Festival, which is where the idea first came to me, it feels unsettling and provocative. Something [feels] deeply ‘wrong’,” says Rickett. “It would have been one thing to signal rebellion through style, gestures, or references to Riot Grrrl or ladette culture – both of which were part of the cultural landscape at the time. But, in wearing business suits and staging the performances in public sites across London, the meaning shifted. It became a critique of power, and of the ways those spaces were – and still are – gendered. The work has sometimes been described as an appropriation of masculinity, but I think of it more as a pastiche.”

Three decades later, does the artist feel there are any parallels between the cultural and socioeconomic landscapes of 1995 and 2025? “Both moments are marked by a sense of precarity, but what’s changed is the framing,” she reflects. “On the surface, things are more open and equitable [now], with improved transparency and institutional accountability. And then other things show how little has shifted: workplace inequality is still an issue, mental health is often dismissed or coded differently for women, and the pressures around ageing and appearance are as normalised as ever. Gendered assumptions don’t disappear; they just keep coming back in different forms.”

Stream by Sophy Rickett is on show at Cob Gallery in London until 27 September 2025.