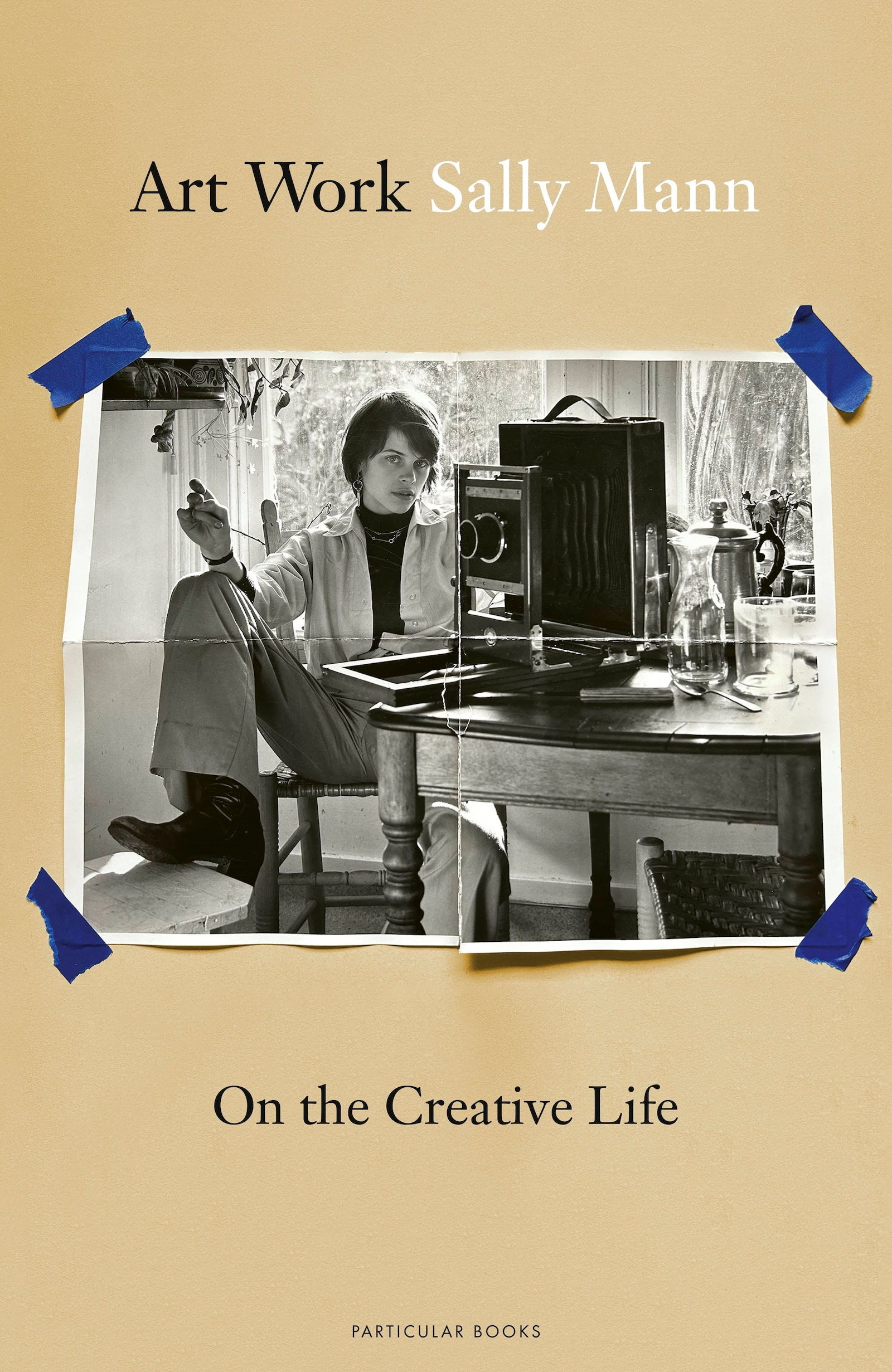

Sally Mann’s venerated photographic practice is deeply personal. Inspired by her surrounding family and community, she takes emotionally nuanced – at times highly controversial – images of life in the US South and its haunting landscape. Following her popular autobiography Hold Still (2015), she has written Art Work: On the Creative Life, which explores her artistic trajectory alongside diary entries and photographs. Loosely, it offers advice on developing a creative career, but this is no simple how-to book. Mann is just as interested in the contradictions and accidental fortunes that have shaped her practice, which no amount of planning could replicate.

“I swore I wouldn’t write another book because it’s really hard!” she laughs when we speak ahead of the book’s publication. Mann calls from her family farm in Lexington, Virginia, surrounded by heaving bookshelves. “But before Hold Still was even off the presses, I was thinking about things I had left out. I am so endlessly self-questioning. I started making notes and it was a slippery slope. Art Work was so casual, I was writing as if I was talking to somebody in person. Hold Still was heavier.”

Mann is candid about the chance meetings and luck that helped to catapult her to icon status – alongside her profound talents – while acknowledging the struggle of entering the art world pre-internet, coming from outside the major art capitals. “I think it’s hard for younger artists to understand what it was like before the internet. There were no galleries down here. It was really a difficult process. There are simpler ways to do it,” she smiles. “Find some rich parents …”

In her chapter on luck, she writes about meeting Ron Winston, son of lauded jeweller Harry Winston, on a plane. He would go on to support her work with a grant. While she can see the impact of such seemingly random connections now, Mann notes how messy it felt at the time. “Retrospective vision is so much clearer than when you’re in the thick of it,” she says. “That’s what’s interesting about going back and reading the letters [in the book]. My utter confusion, chaos and despair. I would say 80 per cent are about my uncertainty, not knowing where to go and how to manage things. It’s just one foot in front of the other eventually.”

“It’s not like I could take a transgressive picture and stick it up on the internet. I was taking pictures that were pushing the boundaries a little bit, but they just sat in my darkroom” – Sally Mann

She has explored the impact of rejections throughout her life, mentioning that they are “excruciating” even now. “They’re humiliating,” she says. “But I do get rejected less often. At a certain point, success breeds success. That’s insidious too. If your success breeds an automatic acceptance and accolades, it’s tempting to get away with the mediocre work we’re all capable of. I think success can undercut your creative efforts.”

Writing Art Work and infusing her prose with images highlights an ongoing connection between the written and visual languages that exists in her process. “Sometimes when I read books, I’ll pull up a picture of what’s being described and that will last a little bit longer than the words,” she says. “[The way words and images work together is] like two people walking on an MC Escher staircase. They’re both walking simultaneously on this little circle.”

Mann’s photography is rooted in the world around her, and as such, she keeps herself open to her surroundings. “If I have a camera around my neck, or in the car, I see things more creatively than when I don’t have access,” she says. “When you’re a painter, you have to set everything up and dredge all the imagery out of your soul. As a photographer, you can just put your Leica around your neck and go. I feel an obligation to fill it with pictures.”

Putting this book together has allowed her to find hidden treats in the archive. “I’m really focused, so when I’m after something, it’s almost like I’m on a wild animal hunt. I am so keen to get whatever I think I’m getting, so I don’t see anything to either side. It’s like hunting a stag but killing a dozen rabbits in the process. Then you go back and say hey, rabbits are actually pretty good! When I go back and look at all the side issues I inadvertently explored [in my photographs], I find they have value.”

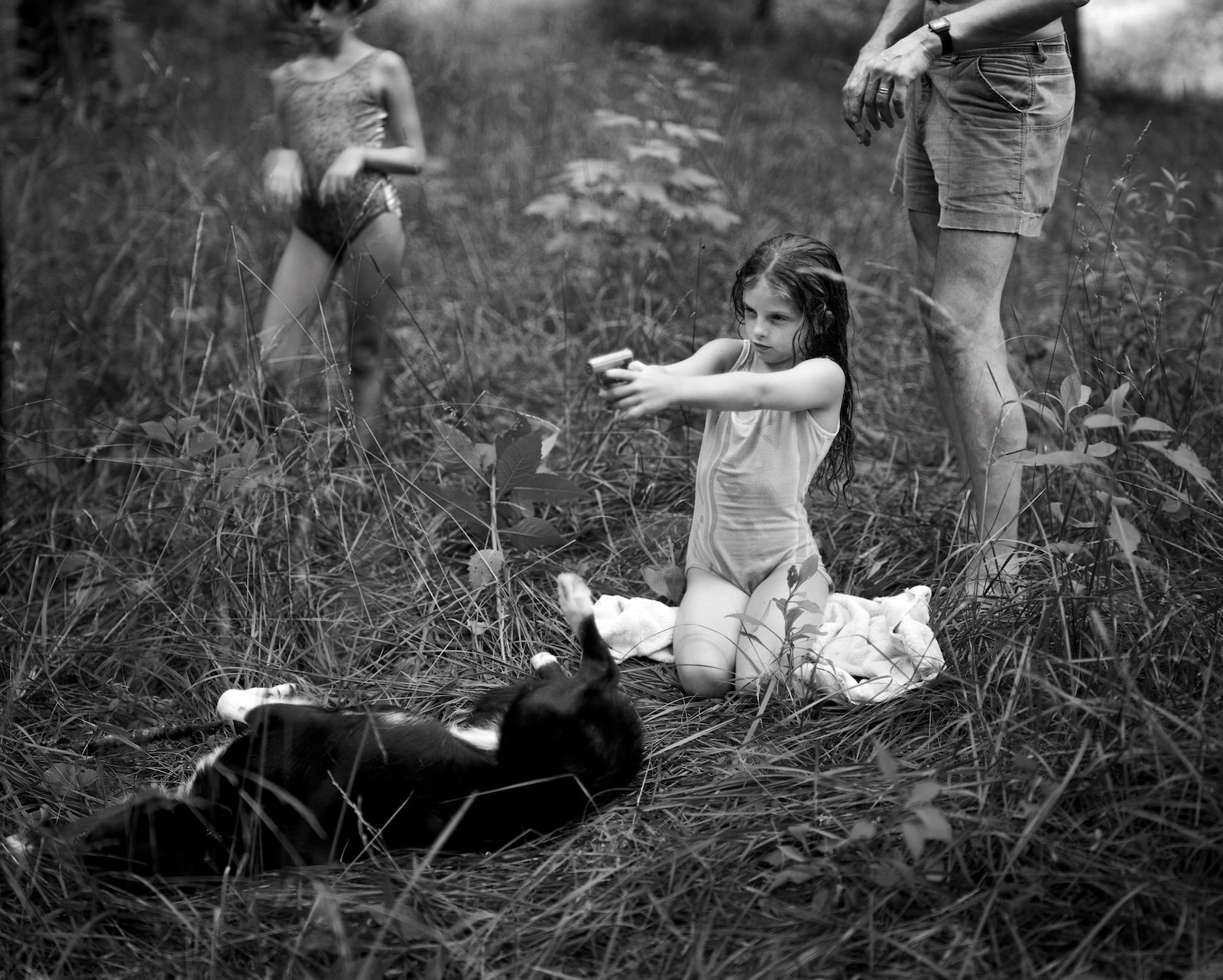

Within the book, Mann addresses her own drive towards “taking risks and violating societal expectations”. One of her most famous images, Candy Cigarette (1989), shows a young girl who appears to be smoking, wearing a white summer dress and staring powerfully at the camera. Photographs of her own nude children first caused debate in the 1990s, with accusations of child pornography. “I never thought they would be seen,” she says of her early images. “It’s not like I could take a transgressive picture and stick it up on the internet. I was taking pictures that were pushing the boundaries a little bit, but they just sat in my darkroom.”

When her book Immediate Family was published in 1992, the work took on a life of its own. She notes that even then, photographers controlled more of the narrative, choosing how to frame, write about and order their works in a way that clearly communicated their intent. “When they get cherry-picked out, they get taken out of context. That’s happened to me a lot.” The controversy still follows her. At the start of this year, a number of photographs were seized from an exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth after a county judge demanded a criminal investigation.

“I didn’t reach out for help to anyone,” she says. “But these anti-censorship groups asked if there was anything they could do. They just stepped in; lawyers offered help. It was great.” This is part of a wider trend she’s noticed of greater community support, especially between artists. “Young people really do want to lift up their friends. I’m a little jealous because I didn’t have that. I didn’t know many other photographers. I think part of it is the political climate in America right now. History is being erased every day, off the walls, out of the books, and it’s unfortunate that we have to be brought together in this way.”

Art Work: On the Creative Life by Sally Mann is published by Particular Books and is out now.