At DoBeDo’s new gallery in south London, an exhibition dedicated to British artist Dick Jewell explores the evolving impact of the image

Dick Jewell’s collages and films are psychologically overwhelming. The British artist plays tricks on the mind, delving into the role of images in the contemporary world. In his new solo show at DoBeDo's new gallery, Grace’s Mews, in southeast London, one wall is covered in images of TV screens at different moments in May 1980. They’re still photographs, but the visual cacophony immediately conjures the frenzied sound and movement of live televisions. There is also a multitude of collages that group images thematically. One shows a series of grinning subjects throwing peace signs. Another combines images of Michael Jackson with his human lookalikes and wax models. The individual photographs are small, drawing the viewer in close and surprising them with visual tricks as they careen between truth and fiction.

“I’d started carrying a camera around my neck as a youth,” Jewell tells me, when we meet for a conversation outside the gallery soon after its opening. Opposite us, a large public collage invites passersby to stop and pose for images to share online; a wry Instagram background from an artist who has long probed our interaction with the camera. He studied graphic design as a way of accessing the college darkroom, which didn’t have its own photography course.

“My work was always about how photography was used in advertising,” he says. “I was also interested in the semiotics attached to the image that people weren’t necessarily aware of. I wanted to make the subliminal messaging plain.” In the second part of his art education, Jewell scoured the phone book and contacted around 70 people who share his last name. He mailed a photo of himself and asked for one of them in return. “I got this really mixed response,” he says. “Some photos were precious family heirlooms going back to the war, which I felt they had entrusted me with.”

The images formed one of his earliest collages. He sent copies of this to all the Jewells, even those who hadn’t replied. More responses came back, continuing a photographic sharing network that mirrors the web of communication we might now find on social media. “Someone sent me about 18 pages of the Jewell lineage going back to the 16th-century Bishop Jewells of Salisbury,” he laughs.

In his early career, he began working with found images, some cut from unsold magazines, others plucked from behind photo booths. At Grace’s Mews, numerous works feature discarded passport shots that have been stuck back together with features missing. “Sitting in the photo booth was obviously the pre-runner of the selfie,” he says. “I found a lot of them thrown behind the booths, where people would also piss. I’d collect them up and wash them in the bath.” He later found out that one discarded image was a test shot of the East Croydon booth mechanic, but many touch on self-image. “It’s about people not being able to accept an image of themselves.”

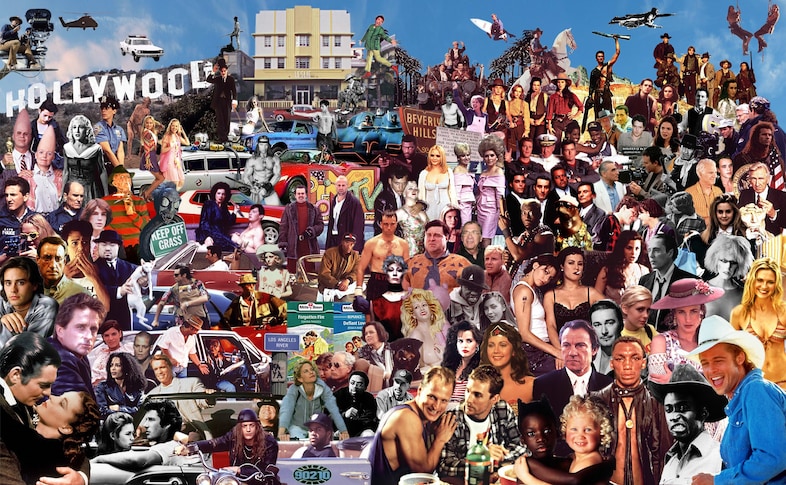

In some of his collages, the line between analogue and digital is blurred. Mona Lisa Private View at the Royal Academy (2024) features a frenetic collection of people dressed as the famous sitter. Some figures near the bottom take on the distinctly smooth form of AI. There is also an image of the living relative of the original painting’s model, La Gioconda. In other works, statues and real people blend together in a crowd, leading to a moment of realisation when the viewer’s perception of a homogenous mass begins to break down.

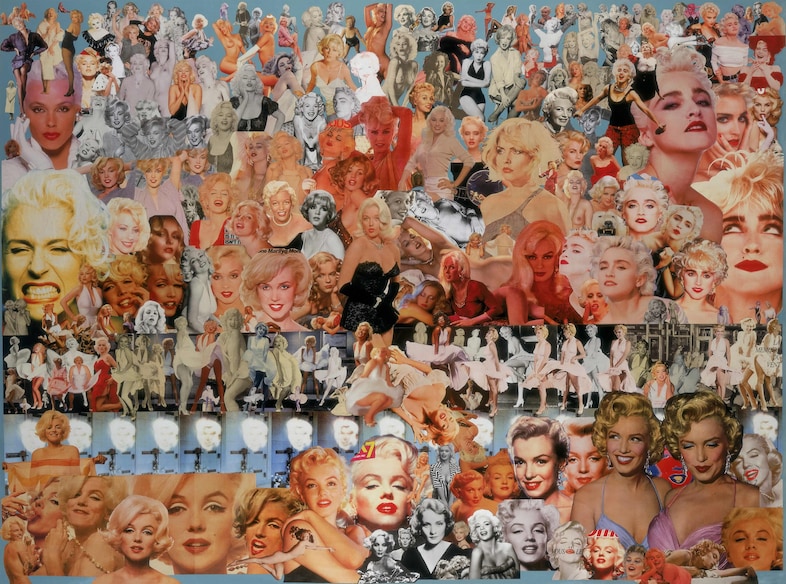

Such works question how we read an image, and the quick assumptions our minds make. Waxo Jacko (2013) makes for a surreal viewing experience, as images of the singer in stages of his physical transformation sit side by side with waxworks and human lookalikes. It is impossible to accurately define each of them. “There were waxworks of him all over the world that he would visit,” says Jewell. “But there was also the aspect of some not being that good, and others being updated over the years with hair and make-up or getting lighter skinned. It was that juxtaposition that I was interested in.” Similarly, in The Marylin Myth (1987), images of the Hollywood icon blend into homages by Madonna and Diana Dors, some more convincing than others. These pieces reflect the tricksy nature of photography and lean into the mythical status these stars ascended to; public image run wild to detrimental effect on the individual.

Jewell’s work feels simultaneously retro and forward-looking, capturing an analogue, scrappy visual culture that has been smoothed out by the internet in some form, but also predicting some of the tenements of the online visual world. The obsession with self-image and lore surrounding famous figures that now runs riot online took root in some of his earliest pieces. The constant push-pull between reality and façade also feels relevant for today’s post-truth digital landscape.

“I always feel like there’s an understanding of my work ten years after I made it. And that’s from the 1970s on,” he tells me. His recent project 4000 Threads looks at how photography is changing culture. “It’s bringing about behaviour like planking and hadouken-ing and all the rest of it!” he jokes. We now live in a world where most people can capture live moments and share online “almost before something has happened”. From the 70s to today, the impact of the image has consistently taken centre stage for Jewell. “That’s always been the premise of my work,” he says. “To encourage people to look and think about what they’re looking at.”

Dick Jewell: Retrospective is on show at Grace’s Mews in London until 23 August 2025.