Curator Vince Aletti and photographer Matthew Leifheit have produced the first posthumous monograph surveying Armstrong’s groundbreaking fashion work

At the tender age of 14, David Armstrong met Nan Goldin at Satya Community School, an alternative high school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Theirs was a friendship that would usher in the arrival of the Boston School, a groundbreaking collective of artists including Jack Pierson, Mark Morrisroe, Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Gail Thacker, who elevated photography to the realm of fine art.

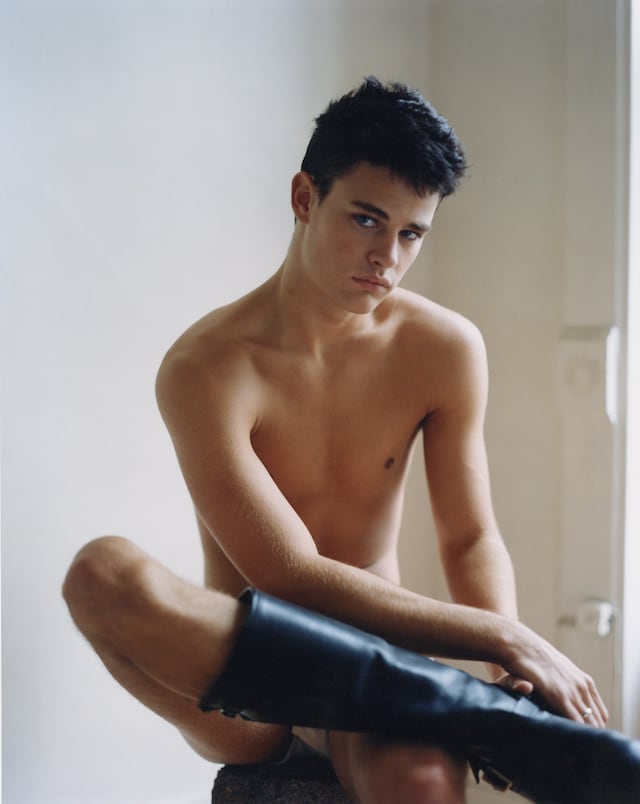

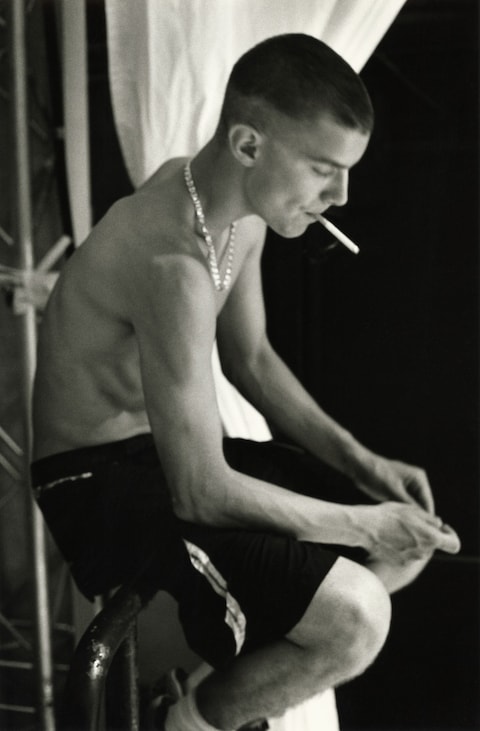

Armstrong rose to prominence in 1981, after receiving critical acclaim for his intimate black and white portraits of friends and lovers on view at the landmark PS1 exhibition, New York/New Wave, later collected in the 1997 monograph, The Silver Cord. “David has always used photography as a seductive device, a sublimation of his desire,” Goldin wrote in the book. “His pictures of people feel tactile because one senses his desire to touch, but never in an aggressive or insistent way. This book is a love sonnet to American style and the Boy as icon.”

Quiet, intense, and imbued with an elegance that evokes the wisdom of Leonardo da Vinci, who observed, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication,” Armstrong’s hypnotic photographs are spellbinding meditations on seeing and being seen. As the most elusive member of the Boston School, he flew under the radar, even when setting the pace.

Crafting captivating images of beauty, smouldering with longing that readily lent itself to fashion at that time, Armstrong stood as the perfect counterpoint to the enchanting fantasias of artists like David LaChapelle, Patrick Demarchelier, and Nick Knight. “What I loathe is modern fashion photography – the bells and whistles and light and foolishness,” he told the New York Times in 2003. “A lot of people just use models as mannequins, so it doesn’t matter who they are. But I don’t. I approach it from the point of view of trying to make a fashion photograph into a portrait.”

Now, more than a decade after his death, critic and curator Vince Aletti and photographer and publisher Matthew Leifheit have teamed up to create David Armstrong: Fashion (Matte Editions), the artist’s first posthumous monograph. The book brings together 107 works made between 2002 and 2010, many never before seen works made for fashion magazines and brands, along with conversations with Lisa Love, Jae Choi, Marie-Amélie Sauvé and Ethan James Green.

Leiftheit and Aletti selected the images from 18 boxes simply labelled “Fashion”, contained within Armstrong’s Brooklyn archive. At the end of the book, the photographs are carefully indexed, the names of most models perfectly catalogued, details on the shoots noted where available, affixing them to a time and place that pulls us back to a reality that lies outside the frame. Where Henri Cartier-Bresson taught generations to seek the decisive moment, Armstrong eschewed anticipatory tensions for the decorous pleasure of the gaze itself.

”I think when you work on something, you think, ‘OK, what just happened, and what’s going to happen?’” Armstrong told Ryan McGinley in a text that appeared in his last living monograph, 615 Jefferson Avenue. “But with my work, I think, ‘Nothing. This is it. This is what happened. There’s nothing before and there’s not something after. This is a portrait, it’s not about a narrative.’”

Before moving upstate to the Berkshires in the final years of his life, Armstrong lived at 615 Jefferson Avenue, a historic four-story row house in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, which he restored to its sumptuous 1899 glory. Choosing reclusion over the world outside his doors, he devoted himself wholly to his art. “David Armstrong was naturally fabulous his whole life, and at that point [early 2000s] he finally had money so he could live out some of his dreams in a realer way,” says Leifheit. “His whole house was a museum of curated antique pieces and he was making assemblage sculptures that he showed later in his life.”

Armstrong, who studied painting before he took up photography, never strayed far from his roots as a painter, his sensibilities finely attuned to a sense of timelessness. ”David was born in the wrong century,” Goldin also told the Times in 2003, a nod to his penchant for 19th-century sensibilities that add a delicate layer of romance and reverie. Armstrong’s photographs, made for magazines such as AnOther Man, Dazed & Confused, French Vogue, and Purple, brought the languorous vulnerability of the Boston School into the world of fashion.

Simply put, Armstrong knew how to get what he wanted. “He used the production of the fashion set, the stylist, hair and make-up, everything to his own ends,” says Leifheit. “When everything had been done, he would ask everyone to leave the room except the model so that he could have the intimate experience of portraiture. Despite the production of a fashion set, he’s able to get something very intimate. If you were hiring David Armstrong, you were hiring an artist and wanted to work within his world.”

David Armstrong: Fashion by Vince Aletti and Matthew Leifheit is published by Matte Editions and is out now.