As the quilt is displayed in an art institution for the first time, Charlie Porter and Pam Hogg reflect on its cultural importance. “The vastness of the Turbine Hall is comparable to the devastating loss,” Hogg says

SILENCE=DEATH reads one of the starker statements to emerge from the Aids crisis. Accompanied by an inverted pink triangle on posters, T-shirts and badges, the statement was made into a powerful visual by a collective including Avram Finkelstein, Chris Lione, Jorge Socárras, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff and Brian Howard for activist organisation ACT UP (the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power). Confronting prejudice around the onset of the Aids crisis, which delayed investment in research and impacted governmental and society-wide sympathies, it remains today one of the most powerful visual statements on the importance of public protest.

The Aids crisis, emerging in 1981 as a disease disproportionately affecting the queer community, demanded louder statements in order to wake up an ambivalent public. Following a march in San Francisco in 1985, hundreds of protesters affixed cardboard placards naming individual loved ones lost to Aids on the Federal Building – showing the sheer scale the disease had ravaged upon the city. To activist Cleve Jones, the brickwork of names resembled a quilt, a comparison made only more powerful by the irony of the discomfort it conveyed.

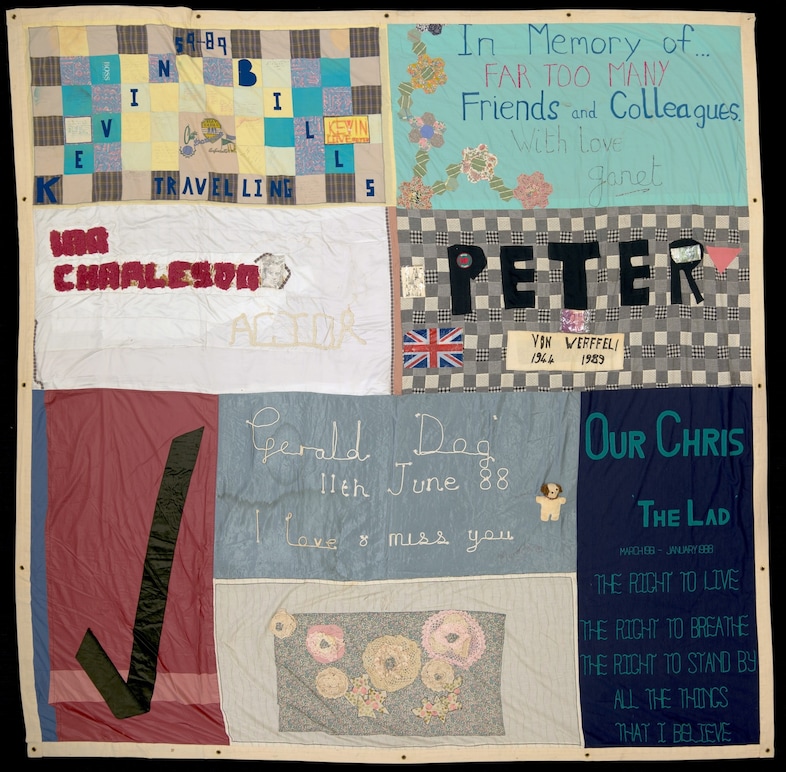

Inspired, Jones established the creation of a dedicated Aids Memorial Quilt (also referred to as the NAMES Project), formed of eight 6x3 foot panels, each dedicated to a person or group lost to Aids and roughly the size of a single burial plot. The project inspired similar tributes around the world, with Scottish activist Alistair Hulme bringing the concept to the UK. Unsupported by the significant charitable structure that backed the US quilt, the UK Aids memorial quilt has hitherto been managed more informally, and is today looked after by a partnership of HIV/Aids charities navigating the competing demands of careful storage and public display.

In researching his recent novel Nova Scotia House – whose protagonist lives with HIV whilst grappling with the effects of Aids in his community – writer Charlie Porter observes how the quilt became a powerful symbol of the crisis. “Being in the presence of it is just the most profound, devastating and humbling experience” he explains, recounting his first encounter with the quilt at the European Aids Conference in London in 2021.

Engaging with the partnership conserving the quilt to discuss incorporating it into his novel, the realisation came that it should be given a more public platform to amplify the multitude of stories it contains. “There are panels that immediately take you to the homophobia at the time, what it felt like in those times,” he continues, “There are panels that are joyful. There are panels that have barely anything on them. There are panels that are of such elaborate technique. There are panels that are super amateur. And the thing is, they are all as important as each other. There’s no hierarchy with the quilt, it’s all these people all together.”

For Porter, the most appropriate home for the quilt was Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall and conversations quickly led to its upcoming display this June. “The power of the Turbine Hall is immeasurable. To me, it is the equivalent of the National Mall in Washington [where the US quilt had been displayed in the early 1990s]. I can’t think of another site in the country with the same power.” Previous displays of the UK quilt have added layers to its meaning, whether in London’s Hyde Park in 1994, St Paul’s Cathedral in 2016 or in smaller sections at various venues around the country. The size of the full quilt (which has been continually added to since its creation) has meant it has rarely been shown in its entirety, and never previously so in an art institution.

The display provides a valuable site of commemoration and collective mourning for those affected by the vast losses caused by HIV/Aids, including those who contributed panels to the original quilt. These include designer and artist Pam Hogg, whose panel is dedicated to friends John Crancher, Vaughn Toulouse and Frank McKewan. “I can’t think of a better place for it to be seen,” says Hogg ahead of the display. “The vastness of the Turbine Hall is comparable to the devastating loss.”

Asked about the potential impact on younger generations with more distant ties to the initial crisis, she says: “If they are not already acquainted with many of the artists, it will be a learning curve, [an introduction to] the massive creative force of so many and their significance in shaping the world.” Purposefully unanchored to specific Aids-related anniversaries, the timing of the display, as Porter explains, is significant in itself, especially at a moment where freedoms and rights for various minorities are being threatened and HIV/Aids continues to impact communities around the world. “It’s more important than ever,” he says. “The time is always now.”

The UK Aids Memorial Quilt is on display at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall from Thursday 12 June - Monday 16 June 2025.

Screenings of There Is A Light That Never Goes Out, a film on the quilt’s display at Hyde Park in 1994 (featuring contributions from Judy Blame, Neneh Cherry, Sam McKnight and Boy George) will be taking place at Tate’s Starr Cinema.