“Seeing all my pictures assembled in one very large room threw me off a little,” Jeff Wall says. The Canadian artist is speaking from Lisbon, days before the opening of his landmark retrospective at MAAT. “Each picture seemed so unrelated to the next. I had this odd feeling that I was this wayward person who has bumped along from one thing to another, wandering around the world with my head in the clouds.”

Wall’s self-effacing review is refreshing, if not a little surprising. While this might be his largest display in Portugal to date, the groundbreaking artist is no stranger to taking up space on white walls. He’s been the subject of several monumental displays at some of the world’s foremost artistic institutions – including Tate Modern, MoMa, Fondation Beyeler and White Cube Bermondsey, just earlier this year. But unlike other shows – where Wall might use rooms to suggest affinities between his works, each its own distinct “vase of flowers” – in Lisbon, he was presented with a new challenge: occupying a vast, elliptical museum space and the curved tunnelled gallery beneath it with his life’s work. He has described it as akin to installing in a spaceship.

Sucking the viewer into 60 different large-scale tableau scenes, Time Stands Still presents an affecting journey into Wall’s influential four-decade career. While his images may initially appear as documentary, they are in fact subtly staggering works of artifice. Wall reconstructs memories – interactions witnessed in the street, flashes from the news, or scenes entirely of his imagination – that have lodged in his mind and refused to let go. Over the decades, these have spanned moments of public contemplation and private psychological torment; exorbitant wealth and urban poverty; violence and reprieve.

Blending the orchestrated approach of a cinematographer and the careful compositions of a painter, Wall’s work initially confounded some critics, many of whom questioned whether it was ‘real photography’ since it didn’t capture life as it happens. “My work is near-documentary,” he says. “I think of it as more of poem writing rather than prose writing. It has a different kind of accuracy, I think.”

Wall established his practice in his late twenties, already an artist, scholar, and father of two. After earning an MA from the Courtauld in London in the 1970s, he returned to his hometown of Vancouver and started making his revolutionary staged scenes. Taking cues from Robert Frank’s confronting depictions of American life, the gorgeous formality of Goya, and the garish light of advertising billboards seen on a trip to Madrid, he blew up his images and mounted them on hefty light-boxes, causing them to take on an otherworldly glow. The first that caught the world’s attention depicted a violently smashed up bedroom inspired by Delacroix’s painting The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), cementing him as a pioneer of conceptual photography alongside names like Cindy Sherman and Andreas Gursky.

“I like to work at near life-scale because it’s so emphatic and has an enveloping quality. When you see events or occurrences in that size, it seems you are very close to them” – Jeff Wall

“It was the result of ten years of struggling to understand what it is I wanted to do, who I was, what my relationship to these other modes [of art] was,” Wall says. “Since then, I’ve not had to innovate very much in terms of what I do.” While the fundamentals of Wall’s practice have changed little, the incidents that he has chosen to stage have varied vastly. He’s recreated moments of racial tension in the street, imagined the sleep-deprived desperation of an insomniac balled up under his kitchen table, and staged a kidnapping in the desert. He often sits on a memory or idea for several years, waiting for the perfect seasonal conditions, actors or right technical planning to bring something to being. That might mean finding a way for a milk carton to explode perfectly from the hand of a homeless man, or simply allowing the emotional resonance of something to take hold.

The all-consuming scale of Wall’s work is another thing that sets him apart from his contemporaries. When he started, most images were shot to appear in 8x5-inch magazines. “I never set out to make big photos just because I thought big photos were cool,” he says. “It came from looking carefully at painting. Paintings have been around for thousands of years and there are a lot of good ones. There’s a lot to be learned by looking at why they’re good. I like to work at near life-scale because it’s so emphatic and has an enveloping quality. When you see events or occurrences in that size, it seems you are very close to them, and it has a kind of intimacy that I like.”

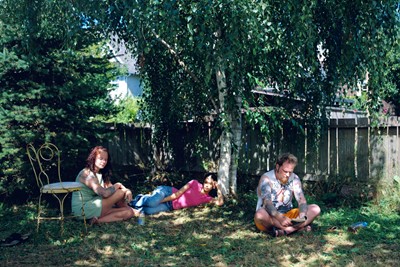

Walking through the space in Lisbon, experiencing these huge scenes – especially those that depict human tension or flashes of hallucinatory imagination – is at times overwhelming. But beyond the extraordinary, some of the more gently affecting images in the show are those that capture the everyday, like a group of tattooed friends sitting beneath a tree in summer, fleeting patches of sunshine falling onto the permanent markings on their skin. Or an ink-jet triptych shot in the gardens of an estate outside of Turin, where the peaceful undulating green of three separate scenes is interrupted by an unknown drama between the ground’s staff. “It’s the biggest work I’ve ever made,” says Wall. “I think of it as a three-act play, all of the scenes take place at the same moment. I won’t say more about what’s happening in it.”

What unites Wall’s work, if a thread can be traced between them, is perhaps that they are fragments of life where the edges of our humanity – in all its dark, uplifting, and most surprising forms – are most vividly on show. “It’s hard to explain why something stands out,” he says, when asked what makes a memory or idea stick with him. “Everybody who is alive sees things every day that attract their attention. These moments might seem odd, curious, funny. There are hundreds of them. And they’re pretty forgettable for any number of reasons. But once in a while, something isn’t so forgettable.”

Despite the challenge of arranging his works in the arena-like museum, the stirring magic of Wall’s own work was irrefutable at MAAT, as hundreds filled the space on the sun-drenched opening evening. Peering down from the marble balcony of the upper floor, a dozen little scenes played out below – people greeting one another, chatting in clusters, then falling silent before the glow of each of Wall’s large-scale images. His final thought of our call came to mind: “With my works, I like to think that I’ve done them well, because if I’ve done them well, at least I’m satisfied – and that suggests that others might be too.”

Time Stands Still by Jeff Wall is on show at the Museum of Art, Architecture & Technology in Lisbon until 1 September 2025.