The acclaimed artist talks about My Mother and Eye, a new series of collaged photographs that reframe the often complex phenomenon of the mother-daughter relationship

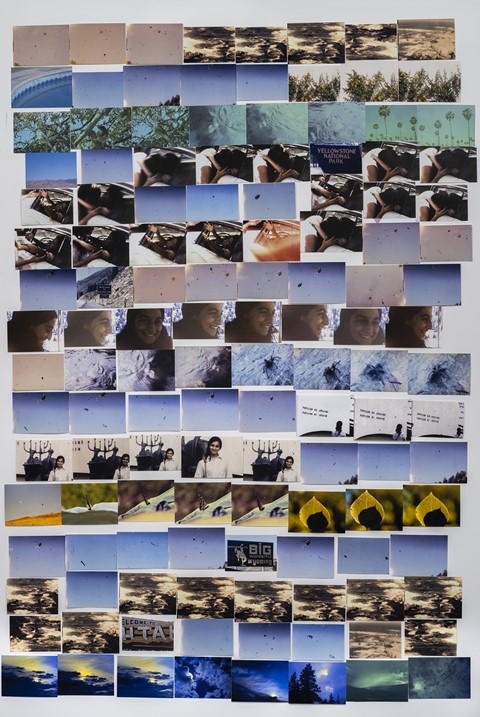

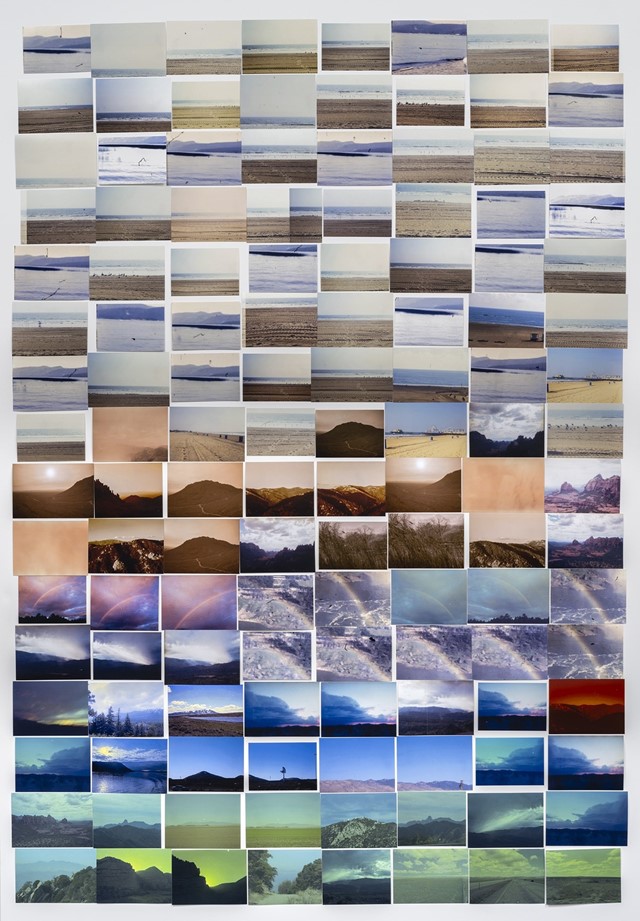

“At 18, I never saw my mother as anything but my mother. I didn’t think of her as a young woman with her own history, her own struggles,” artist Carmen Winant says. “I hadn’t even realised she took a road trip at my age. That awareness only comes later, when you start to see yourself in the past she lived.” I’m speaking with Winant from her home and studio in Ohio over Zoom. We are discussing her latest project, My Mother and Eye, a series of collaged photographs displayed across 300 JCDecaux bus shelters in New York, Chicago, and Boston. Drawing from archival images taken during her mother’s cross-country road trip across the States in 1969 and Winant’s own road-trip at 17, the project layers two histories into a single visual dialogue.

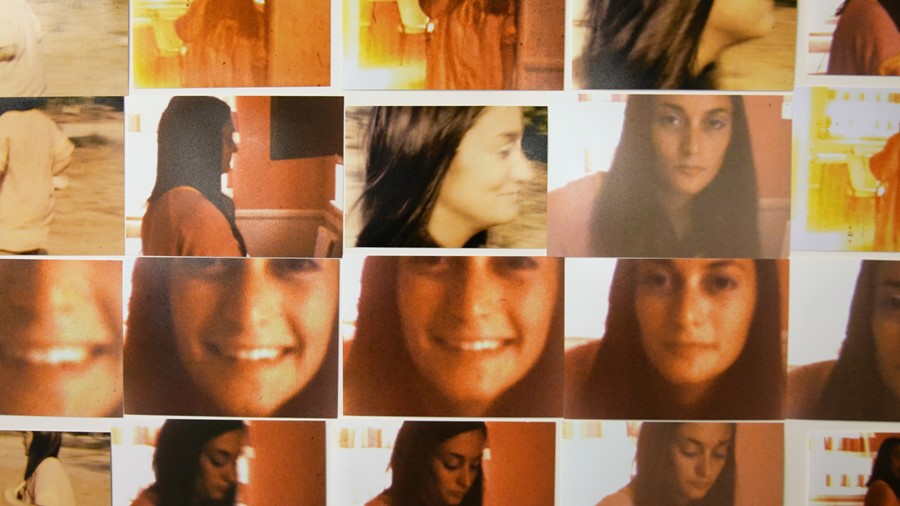

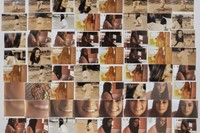

At times, the photographs’ locations are difficult to pinpoint: women stand on a bridge, climb a trail, or an outstretched hand – perhaps Winant’s or her mother’s – delicately sifts through seashells on a beach. Winant’s mother captured her journey on Super 8 film, and decades later, Winant documented her own travels on 35mm. Presented by the Public Art Fund, My Mother and Eye recontextualises private, familial imagery within the public sphere, capturing both a very intimate and personal experience alongside the broader pursuit of autonomy across generations.

Road trips have long represented a particular sense of freedom or possibility within American film and culture. “There’s a kind of nostalgia in all of it,” Winant explains. “Not just because we’re looking at old footage, but because the road trip itself is such an iconic American experience, one that is often romanticised. And yet, what makes their footage so powerful is that it’s not just about mythmaking, it’s about real people, in a real car, on a real journey, with all the complexity that entails.”

Typically framed as a male pastime, Winant’s My Mother and Eye reclaims the road trip as a distinctly feminist act. Her project challenges the notion of movement as a given freedom, instead presenting it as a negotiation: one shaped by gender, circumstance, and historical moment. For women, travel has always carried a different set of risks and limitations, and as much as it signifies liberation, is also a product of privilege. “It’s also about who gets to move freely, who gets to explore without fear,” she explains. By foregrounding women’s perspectives, My Mother and Eye is an assertion of agency, and one that carries both personal and political weight.

My Mother and Eye also reframe the often complex phenomenon of the mother-daughter relationship, challenging the traditional assertion of motherhood as an endpoint. Instead, the focus is shifted to the mother as a person before she assumed that role. “It’s a strange thing to see your mother before she became your mother,” Winant reflects. “To see her as a girl, with her own dreams and fears, completely separate from me.”

This recognition of maternal autonomy is a radical act in itself. Too often, mothers exist in memory, only in relation to their children, their identities flattened by the weight of caregiving. My Mother and Eye resists this erasure, insisting on the mother’s independent existence while simultaneously acknowledging the inescapable inheritance passed between generations. The echoes between Winant’s images and her mother’s, their similar poses and repeated gestures, suggest an inheritance that is not just genetic but experiential. It is an inheritance of looking, of moving through the world, and of documenting one’s own presence in it.

Winant’s work resonates with the theories of Marxist feminist activist Silvia Federici, she quotes the author’s view on caregiving, from her seminal 1974 essay, Wages against Housework. “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work”. “I have always been drawn to the idea that women document their own lives because they have had to,” Winant reflects. “There is a radical act in simply recording oneself moving through the world, not as an object but as a subject.”

This act of self-documentation and the passage of time within the images recall the films of Chantal Akerman, particularly Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and News from Home (1977). Akerman, much like Winant, was deeply invested in the rhythms of everyday life and the slow accumulation of meaning through repetition. “The mundane is never just mundane. It carries weight, history, and tension,” Winant says. “Akerman’s work has always stayed with me, especially her ability to stretch time and show how ordinary moments contain radical depth.”

Winant has long been invested in making women’s histories visible, and her practice is often informed by her mother, a dedicated feminist “in her mothering, in her life, in her work as a citizen, as a neighbour, but also in her vocation.” Her mother worked in international reproductive health. As a result, Winant’s collaged photographic work has often centered on birth, labour, and feminist archives, repurposing found imagery to create alternative historical narratives. My Mother and Eye extends this practice by placing intimate, personal photographs in public space: spaces that are typically dominated by commercial advertising. “The bus shelter is an interesting site because it’s democratic,” Winant says. “Anyone can see it. You don’t have to go into a gallery or museum. It meets you where you are.”

In its layering of images, My Mother and Eye mirrors the fragmented, non-linear nature of time and memory, as a fluid, recursive phenomena that is not fixed and is constantly shifting, resulting in an evolving conversation between past and present. “I was drawn to the idea of collapse,” Winant explains. “Collapsing time, collapsing our two perspectives into one body of work, collapsing the mother-daughter relationship so that it wasn’t hierarchical.” Through montage, their perspectives converge, blurring the distinction between past and present, mother and daughter, observer and subject.

Winant’s project is raw, unstaged, and captures deeply personal and human moments. In a world where women’s images are so often commodified, Winant prioritises presence over performance and reflection over consumption, inviting us to pause, reflect and recognise ourselves in the archive of another. “What I hope,” Winant reflects, “is that people see these images and think about their own mothers, their own pasts. That they see not just my story, but their own.”

My Mother and Eye by Carmen Winant is on show at JCDecaux bus shelters in New York, Chicago and Boston until 6 April 2025.