As a new exhibition of his work opens in New York, we look back on the legacy of Paul Cadmus, an artist who utilised Renaissance techniques in his delicate nudes decades before homosexuality was legalised

As a young artist, Paul Cadmus would walk home from his job at an advertising agency and into the locker rooms of a New York YMCA. “I painted [it] in 1933,” he told Lincoln Kirstein. “I was thinking of Mantegna and Signorelli,” two artists of the Italian Renaissance known for their masterful frescoes. But instead of angels or the condemned in hell, Cadmus painted everyday men in stages of unselfconscious undress. “Often the subject matter of my pictures was chosen because I try to do people with as few clothes on as possible,” he added. “I would rather they were all nude, but … ”

Now, at New York’s DC Moore Gallery, YMCA Locker Room is on display alongside nearly 90 of Cadmus’s works. “They’re beautiful and they’re gorgeous” says Bridget Moore, the gallery’s director, who worked with Cadmus for 15 years until his death in 1999, aged 94. His first exhibition in 20 years, Paul Cadmus: The Male Nudes is the first show to highlight this body of work. “We’re lucky to be able to combine them with eight of his major paintings,” says Moore. “We wanted to show his mastery of drawing and his obsession with it. They’re unbelievably exquisite.”

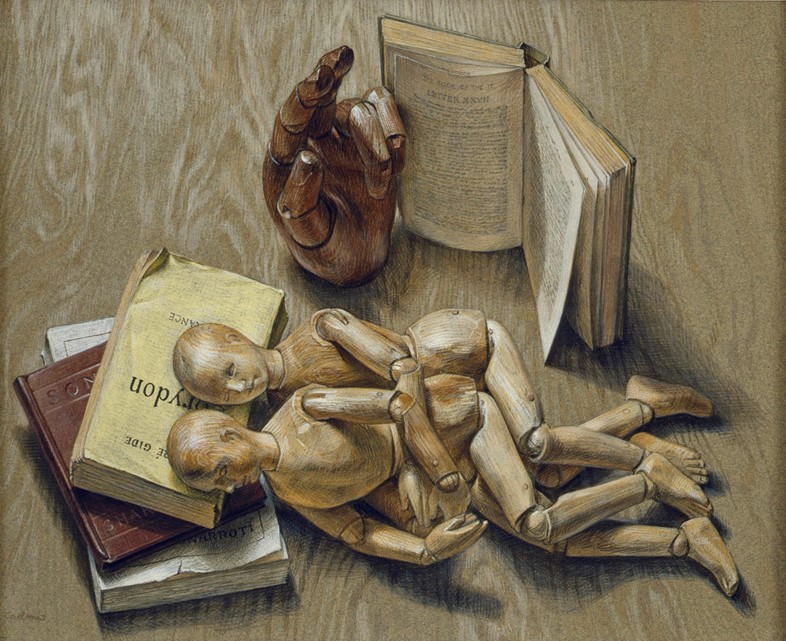

Cadmus once likened his brushstrokes to heartbeats, each one necessary but mostly unnoticeable. Using an old Renaissance technique called egg tempera – very slow, very delicate, very permanent – his life’s output was small. “He was doing so few paintings, he was averaging one or two a year,” says Moore. “So they’re very hard to come by. And when it comes to the drawings, these are works that we as a gallery assiduously collected. They were scarce even in the 80s and 90s, and even more so now. It’s just so hard to see them. That’s one of the reasons why we wanted to do this show.”

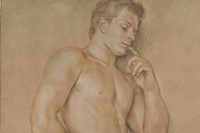

Born in New York in 1904, Cadmus studied at the city’s National Academy of Design where he learned to draw from ancient sculptures and nude life models. His drawings, often depicting his muse and life partner Jon Anderson, are part of this classical tradition, executed with an easy grace that is only achieved by superb technical skill. In ancient Greece, the male nude embodied a metaphysical ideal: the beautiful body reflecting the beautiful spirit within. This tradition was literally unearthed in the 15th century and rediscovered by Renaissance artists like Donatello, da Vinci and Michelangelo, the latter writing, in a sonnet to his male lover: “Nor hath God deigned to show Himself elsewhere / More clearly than in human forms sublime.” God, for these artists, was found in the flesh.

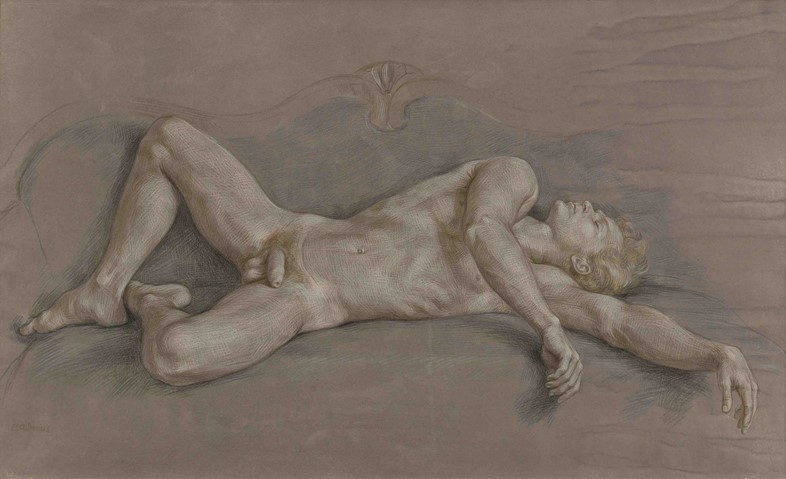

It was Old Masters like these that Cadmus admired on his first trip to Europe in the early 1930s. His nudes have a powerful sculptural quality. Drawn mainly from coloured chalk and crayon, the cross-hatched strokes resemble the marks of a chisel: the figures carved out like marble. Discussing his drawings, he gave a particular anecdote. When a student asked the painter George Luks how best to draw a model, the teacher replied: “You should draw the model towards you.” Cadmus brings figures out of the paper, drawing them to us, like statues, to the extent we may feel we can reach out and touch them.

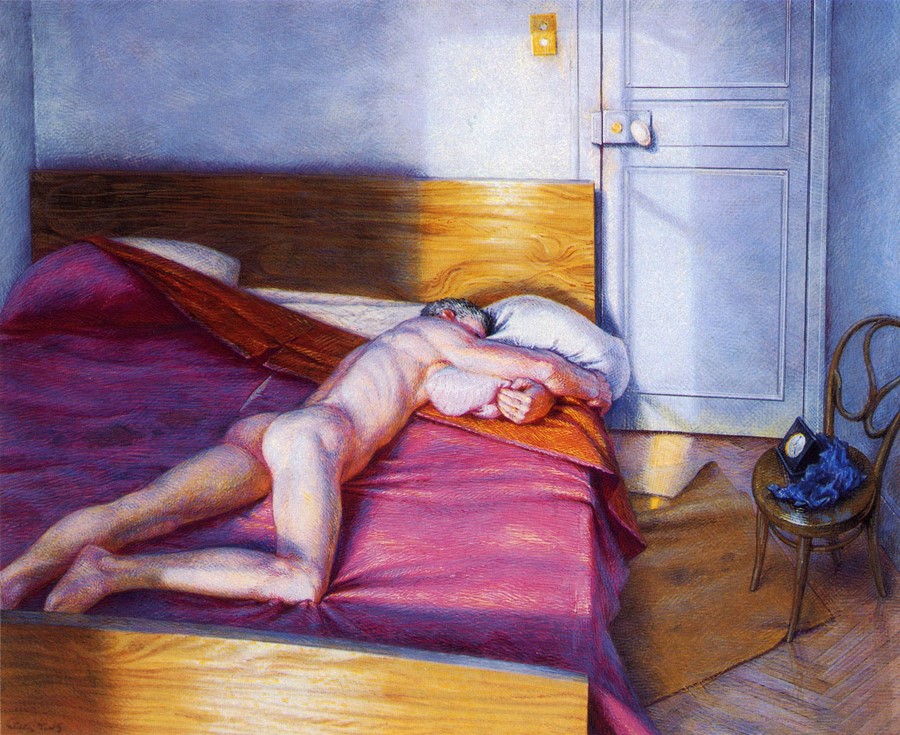

As opposed to preparatory sketches, usually made by artists for paintings, these drawings are finished works in their own right, controlled and carefully composed. “I don’t know whether it’s my own idea,” he explained, “that men are vainer than women in that they work harder at their posing. I mark everything so that the models can get back in the exact position, because, ideally, they should pose like apples or pears.” Like the fruit-laden tables painted and repainted by Paul Cézanne, Cadmus’s drawings delight in the perfect placement of form. His nudes, reclining on sofas and slept-in beds, could well be reclining on plates.

“He knew it wasn’t acceptable to do homoerotic subject matter,” says Bridget Moore. “But he inserted it wherever he could and whenever he wanted to. He had integrity – how he was true to himself and what he was doing. You have to have respect for people who loved this very intimate relationship they had with their medium and did very few works with intense subject matter, knowing that they couldn’t be plastered all over the world. So any time that there are opportunities to see his work, it should be a celebration and should be seen as an opportunity. Because you’re just not able to. Here is a chance to see something that’s really worth coming to see.”

Paul Cadmus: The Male Nudes is on show at DC Moore Gallery in New York until 16 March 2024.