As a new show dedicated to Robert Mapplethorpe opens in London, gallerist Alison Jacques talks about showcasing the photographer’s less famous portraits and still lifes

Over the course of his brief but wondrous life, Robert Mapplethorpe was a seminal force in elevating photography to the realms of fine art. Guided by a clear vision, steely determination, and impeccable grace, he crafted images that confronted the proscribed confines of both politics and art by challenging authority on the very ground it stood.

But Mapplethorpe would not live to see the fruits of his success, and died from Aids-related illnesses at age 42 in 1989. Knowing he had not yet fulfilled his destiny, he established the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation a year earlier to ensure the mission continued without him. He died amidst a flurry of controversy around The Perfect Moment, a touring solo exhibition featuring provocative scenes of gay BDSM that ignited the wrath of neoconservatives hell-bent on persecuting that which they deemed “obscene”. Invariably, they lost but the damage was done. In the decade following Mapplethorpe’s death, his books were banned, his work censored, his name synonymous with scandal. But Michael Ward Stout, president of the Foundation handpicked by the artist himself, soldiered forth, knowing there was far more to Mapplethorpe’s legacy than what the public had seen.

In 1999, Stout invited gallerist and curator Alison Jacques to an exhibition at Hamiltons in London – an encounter that would change both their lives forevermore. “I went to the show and the first thing I saw was a Polaroid that Robert had made in the early 1970s before he started making larger format photographs,” Jacques tells AnOther. “If you look at this body of work, which was completely unknown in 1999, you see all the ingredients [of his vision]. I was very intrigued by it so I inquired with the Foundation and the director told me it was the first time they had ever shown a Polaroid.”

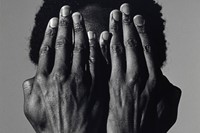

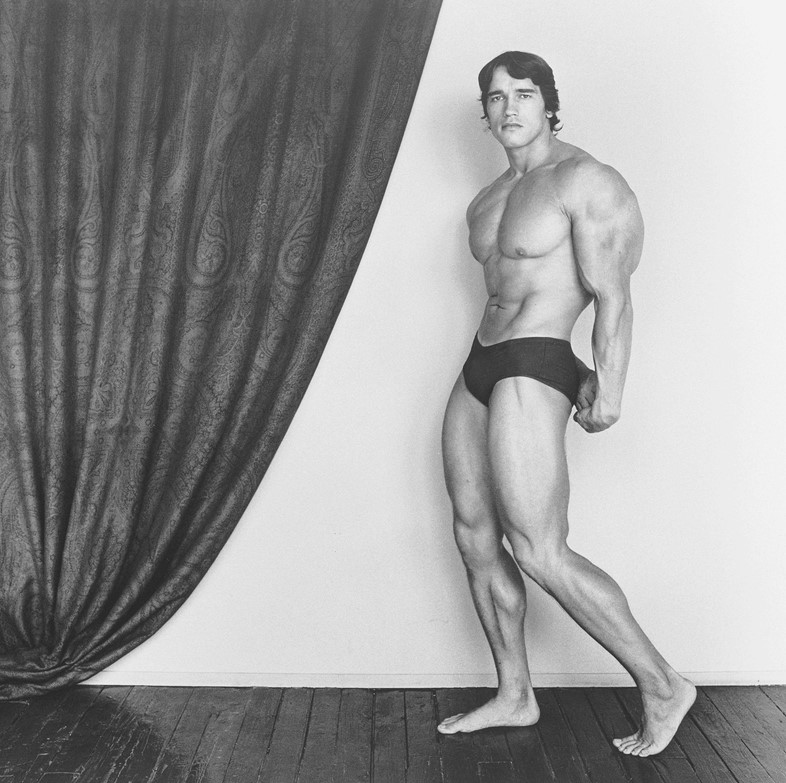

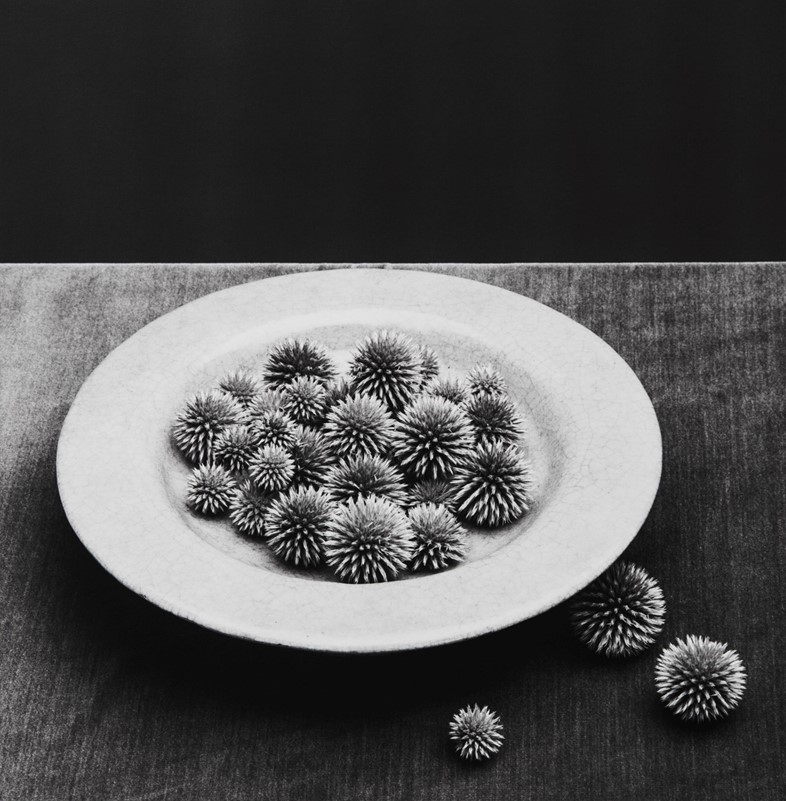

From that encounter a partnership was forged: one that began with Jacques’s first exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids and has continued for nearly a quarter of a century. To celebrate, Jacques has curated Robert Mapplethorpe: Subject Object Image, a selection of rarely exhibited works made between 1976 and 1989 across portraiture, still life, and flowers that explore the artist’s singular ability to distil the sculptural essence of the two-dimensional realm.

With meticulous attention to lighting, composition, and detail, Mapplethorpe understood the perfect photograph required the same level of care and construction a painter might render. Whether shooting luminaries like Yoko Ono, Paloma Picasso, Andy Warhol, Willem de Kooning, and Patti Smith, or crafting delicate images of orchids, roses, antique silverware, and Venetian glass, he recognised that both figure and form share the same sculptural qualities. “It’s a different subject, same treatment, same vision, which is what it’s all about – my eyes as opposed to someone else’s,” Mapplethorpe said in 1983.

But by and large, he preferred to let the images speak for themselves. “If you say too much, you lose some of the mystery that ends up being there,” he said in the 1988 BBC documentary, Arena: Robert Mapplethorpe. “Somehow I am able to pick up the magic of the moment and work with it. That’s my rush in doing photography; you can get to a place where you can do it with a flower, with a cock, with a portrait ... You’ve tapped into a space that is magic.”

After collaborating with the Foundation for 24 years, Jacques is exquisitely attuned to the exquisite blend of sacred and profane energies that masterfully co-exist in the artist’s work. “He lived a life of contradiction in the hedonistic underground culture of Studio 54 and the BDSM subculture, while mixing with uptown people in music and art,” she says. “Robert was creating images that were about the times in which he lived and making work that was pushing boundaries in New York’s conservative environment. He wanted to show the underground life, which he and a lot of people were living, because it was hidden.”

Beyond the pleasures of the flesh, Mapplethorpe was fascinated by the implicit relationship between sculpture and photography. The exhibition includes one of his first sculptures, a grilled mirror in a simple wooden frame that opens the show. “When you come in, you see yourself so that you become a subject, an object, and an image in his sculptural mirror,” says Jacques, alluding to the exhibition title, Subject Object Image, which she personally curated.

While guest curators including Juergen Teller and David Hockney have previously organised shows, Jacques decided to bring the depth of knowledge she has acquired over the years to the new show. “From the very beginning in 1999, I’m trying to show [lesser or unknown] aspects of Robert’s work,” she says. “He’s now an iconic artist and people think they know his work, but he worked in so many different areas and themes. It’s my role as a gallerist to lend him a voice.”

Robert Mapplethorpe: Subject Object Image is on show at Alison Jacques in London until 20 January 2024.