As a new collection of Vietnamese modern art at Sotheby’s in Paris goes on sale, Sotheby’s head of department for Asian arts – Christian Bouvet – tells us the story behind the works

A new collection of Vietnamese modern art at Sotheby’s in Paris brings some of the biggest names – who were exiled in Paris in the middle of the 19th century – together with rare pieces by artists who lived and worked in Vietnam. Lê Phổ and Vũ Cao Đàm were modern masters who combined traditional elements of Vietnamese painting and iconography, such as the use of silk instead of canvas and symbolic animal relationships, with the emerging styles of the global modern art market.

The works shown in the collection of scholar and collector Prince Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Lộc evoke a sense of nostalgia. “There was a huge part of Lê Phổ’s career when he was represented by an American gallery who asked him to please Western taste,” says Christian Bouvet, Sotheby’s head of department for Asian arts. “The things he was selling to the prince … they shared as a common interest. They were still modern works – him and Vũ Cao Đàm were the Picassos of Vietnam and they were breaking through with new styles – but using classic mediums.”

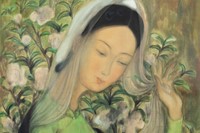

Many of the paintings are serene and delicate. One oil on silk work by Lê Phổ shows a woman sipping tea enveloped by an explosion of bright yellow flowers, with the semi-flattened perspective offering a hazy, illusive sense of space. Another of his works depicts a pair of Mandarin ducks circling each other in courtship, surrounded by rich foliage and fragile petals. “It is a traditional symbol of marital bliss as the ducks stay together for life; when one dies the other stays alone,” says Bouvet. “You have the lotus flowers also. It’s a rare work made with gauche and pigments on silk, which would never have been sold to westerners.”

Many of the pieces have a sense of escapism or longing, transporting viewers to peaceful scenes that seem to exist outside of the industrial modern world. “The Vietnamese community in Paris at that time had a sense of exile,” says Bouvet. Some works are personally nostalgic too. Lê Phổ’s Lady with the Veil depicts a young woman with rosy cheeks and her head covered in sheer white fabric which she holds up with her hand. “I think this is idealised,” says Liting Hung, department coordinator of Asian art in Paris. “The artist lost his mother when he was quite young, so he was always looking for maternality. We see a lot of works about mothers and sons, family ties.”

There are also rare works by Nguyễn Tường Lân, who is understood to be one of the founders of modern art in Vietnam. “He died young, in 1946,” says Bouvet. “He is considered a very indigenous artist in that he was never westernised. A lot of work was destroyed in the war. He’s seen as a real soul of Vietnam, while at the same time being very progressive.”

Prince Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Lộc was a cousin of Emperor Bảo Đại, the last monarch of Vietnam. He studied in Montpellier but returned after the Second World War and was involved in Franco-Vietnamese negotiations that led to the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Soon after he moved to France as the diplomatic representative of the State of Vietnam, where he built his collection and developed close ties with the artists within it. “He became friends with Lê Phổ and others in the 1930s and then eventually came to France and continued his career here,” says Bouvet. “Lê Phổ, to begin with, was not making money with his art. The prince asked him to design his apartment.” Items from the opulent Parisian interior are also part of the collection, including a sketch the artist made beforehand.

Bouvet says renewed interest from Vietnamese collectors is helping to redefine the way in which its artistic history is viewed on a global scale. “Many collectors in Vietnam are building museums; it’s about celebrating that tradition with a bit of a nationalist approach. If it hadn’t been for Vietnamese collectors buying these lacquer works back, some artists would never reach the prices that they do. It casts a new eye on the quality of that work.”

Michelle Yaw, Sotheby’s senior specialist in modern art, Asia, sees clear parallels between the work in the collection and the direction contemporary Vietnamese art is taking, from the popular use of lacquer to enduring traditional symbols. “Artists like Lê Phổ and Vũ Cao Đàm celebrated Vietnamese identity by portraying Vietnamese people, as well as drawing on traditional cultural motifs which carry a lot of symbolism,” she says. “Contemporary artists continue to explore notions of the self and Vietnamese identity in a wider international context. There is also a growing number of Vietnamese diaspora artists, or artists that train and practice abroad. These artists may have grown up outside of Vietnam, but their work reveals how they decipher their identities as Vietnamese artists engaging with and living in a wider global context and artistic community.”