For three decades, across her intertwined fashion and fine art practices, Viviane Sassen has been constructing a surreal and photographic universe that draws on the expressive and emotional power of light. The Dutch photographer is the subject of an upcoming retrospective at Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, which is accompanied by a 500-plus page tome by Prestel. They both take the title of Phosphor, which derives from Greek, meaning “bringer of light”.

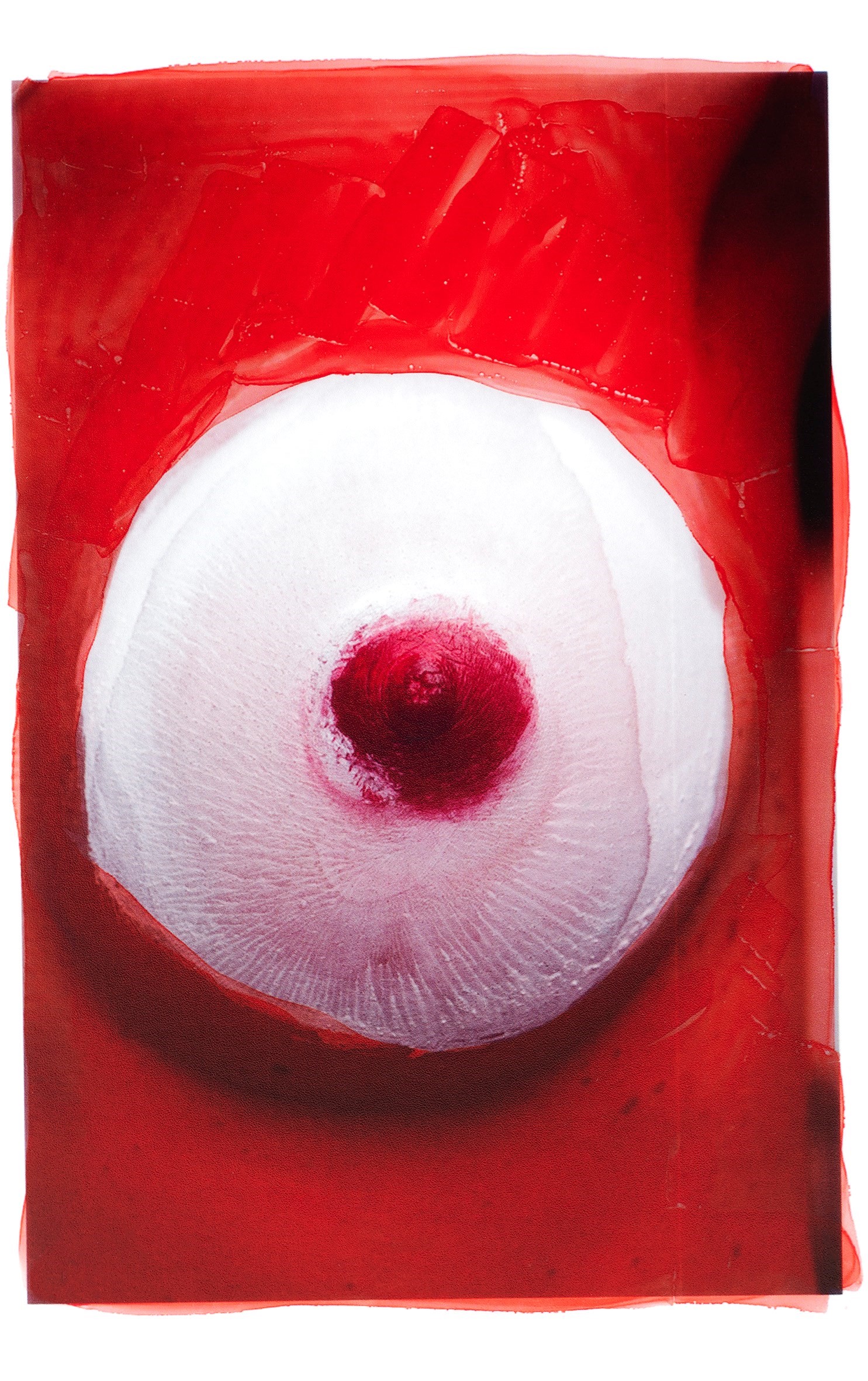

While Sassen has always been unseen – even if infinite – she has released a second, slighter publication in which she is the subject. Entitled Self Portraits 1989-1999, it stretches back to the beginning, featuring some of Sassen’s earliest experiments in photography, when she was imagining and imaging herself for the first time. Brimming with sexual ambiguities and psychic uncertainties, the book lends insights into the inner workings of the photographer as a young woman. In light of the Paris and Prestel retrospectives, audiences will be invited to trace a magical red line that links the old with the new.

AnOther sits down with Viviane Sassen, who speaks about youth, carving out her image, and feeling empathy towards her former self.

Alessandro Merola: When was the first time you turned the lens on yourself?

Viviane Sassen: As a teenager intrigued by fashion, I would sometimes borrow my father’s camera and make ‘fashion pictures’ with my friends. Looking back at them is pretty hilarious. I’d use all sorts of props, like aubergines, as you’ve seen.

AM: You started modelling not long after, right?

VS: Yes. When I was studying fashion at art school, every now and then. Working with those photographers made me realise I wanted to be behind the camera, not just before it. I also felt I wanted to regain some power over my own body, as I grew tired of the male gaze that was so prevalent then. This was in the early 90s, and most fashion photographers were men. Often, they would ask me to act ‘sexy’ in front of their lens, and, although they never crossed a line (with me), I often felt very uncomfortable. They would say things like: ‘pretend I’m your boyfriend’ or ‘make love to the camera, seduce me!’ Making self-portraits felt like taking back control.

AM: What else struck you about the possibilities of self-portraiture?

VS: Looking back now, on a personal level, I guess I was exploring my own sexuality. The self-portraits were a way of me carving out my image. I often referred to myself as a ‘shy exhibitionist’ at the time. That ambiguity suited me, and I think it still does. This was a time in my life, my early twenties, when I was still very much in search of myself, my identity. Having a creative outlet for your inner journey from teenager to adult is priceless. And on a photographic level, making self-portraits was also a very practical thing. I always had my own model at hand. I could make her (myself) whatever I wanted.

AM: What did the 90s look like for you?

VS: Well, I started art school in 1990, when I was 18, and finished around 1997. I studied fashion design for two years, then switched to photography, which I studied for four years. Then I did a Masters in fine art for one year. It was a very tumultuous decade, not only because of first love, first ‘real’ relationships, first time being alone, first time living alone, first time standing on my own two feet, but also because my father passed away. I was 22 in 1995, and he ended his own life. He was suffering from depression because he was in constant physical pain. Despite undergoing brain surgery, he continued having these horrible headaches, day and night. His death has had a huge impact on my life, and those first years were especially difficult. I started getting panic attacks which resulted in an anxiety disorder. At the time, life often felt like surviving. But otherwise, it was still an interesting time. [There were] great parties too.

AM: Were you introduced to art as a child?

VS: My parents weren’t very artistic, although my father started painting and sculpting a bit when he had to stop working after the surgery. His sister was a painter, and my grandfather wrote drama. On summer holidays, they’d bring us to churches in Italy, or museums in the south of France. Modern art as well, but not very contemporary. My father supported my creativity, and so did my mother. She’d help me make my own clothes and Christmas decorations.

“I felt I wanted to regain some power over my own body, as I grew tired of the male gaze that was so prevalent in the 90s” – Viviane Sassen

AM: What art caught your eye?

VS: Firstly, my parents’ art books. Gauguin, Modigliani, van Gogh, Matisse, all the classics. They also had these wonderful photo books by Peter Beard and Mirella Ricciardi about East Africa, which they bought in Nairobi when we lived in Kenya in the early 70s. There was also a lot of reggae in the house, but also classical music. Stevie Wonder, Barbra Streisand, Paolo Conte, The Rolling Stones, The Beatles – all favourites.

AM: The bodies in your work have always taken on sculptural qualities. Photography is the language of light, but also of forms! Where did your interest in the body come from?

VS: My father was a doctor, so I think there was always this special attention towards the body. And in Kenya, we lived next to the ‘crippled home’ where kids were treated for polio. They were my friends. I’d play with them in the playground. I was too young to understand the seriousness of their deformations, which were caused by a very severe illness. I’ve always been intrigued by the body and the shapes it can make. A body can transcend an emotion.

AM: Tell me about the collages and paintings in the book.

VS: I recently found all this early work and was pretty surprised to see that the collages and paintings were things I did from a very early point in my practice. Some were even made during my first year at art school. It’s funny. I’ve been making images for over 30 years now and, suddenly, I realised that I’ve been doing the same stuff over and over again! It makes you wonder, do we, artists, really evolve and grow, or do we simply repeat the same things again and again, unconsciously?

AM: How do you edit your books?

VS: Very intuitively. I make tiny prints of all the pictures I might want to use, start editing down and combining images on A4 paper, folding them like double-page spreads. I tape them on once I’m happy with the combinations, and then sequence them. I have to do it manually – or analogue – because I don’t have the same feeling and overview on a computer.

AM: You made little books in art school, right?

VS: Oh, that was pure horror! Imagine making an elaborate layout of a book, with some images having to align on different pages, some you want to run across a spread, others to be exactly in a corner, some small, some enlarged. But you have no computer. Your source materials are postcard-sized prints. And you have a colour copy machine from the 90s. Good luck!

AM: You’ve previously said that you don’t see a project finished until it’s in a book?

VS: Yes. I feel it’s like cleaning up my closet. Once the book is out in the world, I feel relieved. It will go its own way, as it’s out of my hands. Books are so democratic. I started collecting photo books as a student, because one of my teachers encouraged us to do so. As a student, you can’t afford an expensive print, but you can buy a book.

AM: How do you feel about looking back at early work? What I love about the book is that it’s so ‘Sassen’ … And that’s a compliment!

VS: Oh, thank you! I think some of it feels immature, but I can appreciate it for what it is. I look back on these images and have a kind of empathy for the person I see. But yes, I think it’s fun to see those early attempts, also because they do relate to the work I made afterwards. There’s a stream of ‘unconsciousness’ that connects the then and now. I like that.

AM: What would you tell the young you?

VS: ‘Don’t be afraid. You’ll be alright.’

Self Portraits 1989–1999 by Viviane Sassen is published by Kominek Books and is out now. Phosphor: Art & Fashion 1990-2023 is on show at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris from 18 October 2023 – 11 February 2024.