A new exhibition in London showcases the photographer’s disarmingly intimate portraits that served to counter the LGBTQ+ community’s demonisation in society

In 1965, Lisetta Carmi was invited to a New Year’s Eve party in her native city Genoa, where she was born in 1924 to a Jewish family. By then in her early 40s, and already an accomplished pianist and experienced political activist, Carmi had recently turned her attention towards photography, focusing initially on the harsh labour conditions of the city’s dockworkers. But at the party, she found a subject matter that would trump her interest: Genoa’s trans community.

Over the next few years, Carmi immersed herself in the clandestine world of the city’s trans community, a project which in recent years has sparked renewed (yet belated) interest in her work. Lisetta Carmi: Identities, the first UK exhibition dedicated to her humanistic lens and unconventional start as a photographer will open at London’s Estorick Collection this month. A year since her death, the show situates her importance in the history of Italian photography.

Structured in two parts: the first highlighting her series about the dockworkers (‘Genova Porto, 1964’) and the second, focusing on her portrayals of the city’s trans community (‘I Travestiti, Genova, 1965–67’), the show reveals the socio-political impetus behind her work. “Carmi’s work sought to represent those struggling to assert their identity, whether it be gender or class,” curator Gianni Martini tells AnOther.

Although same-sex sexual activity had technically been legalised in Italy in 1890, under fascism during the Mussolini years, those who deviated from the heterosexual norm, were treated as ‘degenerates’ and even expelled from their homes and sent into confinement, sometimes to prisons on islands off the coast of Italy. In general, expressions of queerness were not tolerated in a Catholic conservative society and cross-dressing remained a punishable offence under Italian law until 1981.

But in the port town of Genoa, queer communities found a degree of refuge, especially among the dark alleyways of the historic Jewish ghetto of the city, between Piazza Fossatello and Via del Campo. According to Martini, this area of the city was “where the transgender community could live without coming into conflict with the local population”. Obscured in the dark network of the dimly lit, narrow backstreets, they could hide from the police, but also express themselves in a contained, public space. “Transvestism was illegal in the 1960s, so it was crucial for trans people not to be identified, to avoid arrest and the 'foglio di via' (travel warrant) – the obligatory return to their places of origin and families, who often ignored their choice of life,” Martini explains.

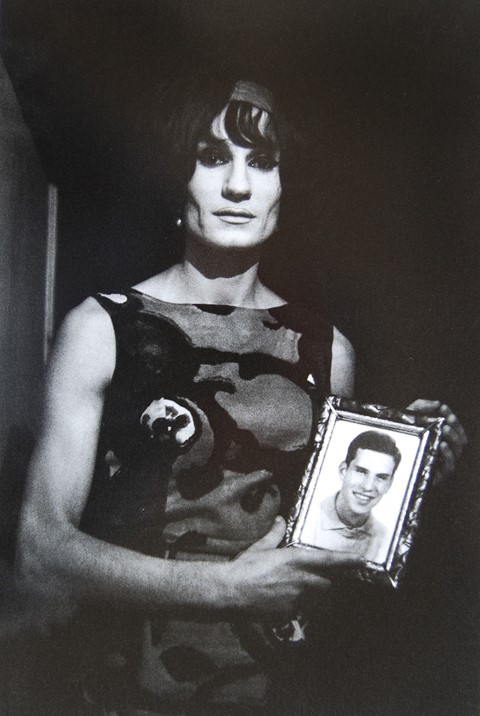

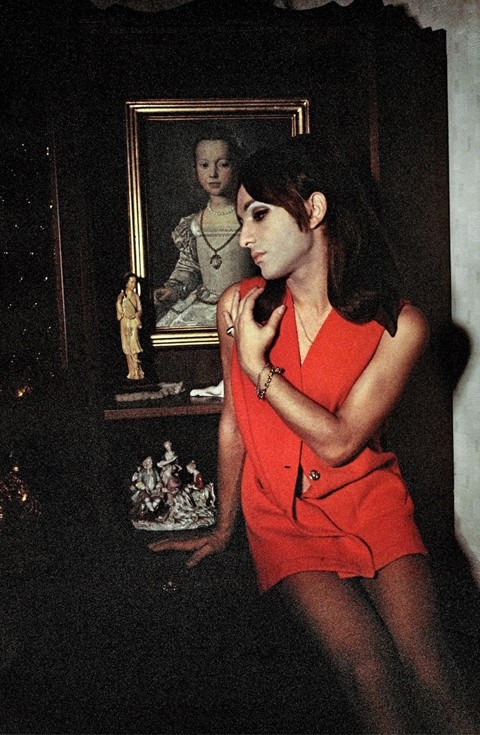

As a Jewish Italian woman – who was expelled from high school following the racial laws issued against Jews by Mussolini in the late 1930s – Carmi undeniably felt like an outsider in her own country. Her acceptance into the trans community was founded upon her deep compassion and curiosity, but desire to rouse empathy for those who experienced discrimination. She typically captured her subjects in moments of private repose, in quiet domestic interiors where they posed candidly for the camera; applying their makeup or posing in sexually provocative or playful manners. Such disarmingly intimate portrayals served to humanise and counter their demonisation in society.

As the series of photographs reveals, visual symbols reflecting Italian history, art and the iconography of the church play a prominent role. “Their homes are middle-class houses with reproductions of paintings by Bronzino, bedrooms with furniture painted in the Venetian style and old-fashioned telephones,” Martini adds. The enmeshing of symbols relating to Italy’s rich church-affiliated history and culture (treated with reverence) alongside the castigated trans community (treated with contempt) conflated two worlds, which in 1960s Italy were considered to be quite separate, or even antithetical to one another.

“I immediately understood that these were human beings who experienced, and suffered deeply from, the contradictions of our society, a minority that was both sought out and rejected,” Carmi reflected in 1972. According to Martini, “Trans people were rejected by bourgeois society, which denied them any rights and the right to work, but at the same time, men from all walks of life (including the clergy) hunted transgender people for sexual purposes.”

“Carmi herself experienced problems with the male/female identification,” adds Martini. “Or more precisely, she rejected prescribed gender roles.” In one text Carmi aligned herself emphatically with transvestism, not only as a sexuality but as a state of being, writing: “they helped me to accept myself for what I am: a person who lives without a role. Observing transvestites made me realise that everything that is masculine can also be feminine, and vice versa. There is no obligatory behaviour, except in an authoritarian tradition that is imposed on us from childhood.”

Carmi’s exploration of an oppressed community – who defied the moral social codes of the time – was not merely to shock her contemporaries. She sought to give visibility to Genoa’s trans community to further her own personal and political vindications: the need for a radical re-examination of gender roles under patriarchy. Unsurprisingly, publishers were hesitant to take up the project. In 1972, after several years of tenacious searching for representation, she received the support of Sergio Donnabella, who financially backed the publication of the volume titled I travestiti.

The body of work revealed her tender and compassionate observation of the trans individuals she met, many of whom became her close friends. “Her deep respect meant that she was accepted from day one, with sincere trust and friendship,” Martini explains. The series of photographs powerfully conveyed the trust between photographer and subject. “I never sold a photograph of them, despite the fact that I could have made money by doing so; for me, it was more important not to ruin our friendship” she later wrote.

Whether in the privacy of their own homes, or in the piazzas and mediaeval alleyways of Genoa, Carmi created an unorthodox visual language that expressed the paradox of the trans community’s position: their fight for empowerment alongside their undeniable vulnerability in a traditional Catholic society.

Lisetta Carmi: Identities is on show at the Estorick Collection in London until 17 December 2023.