A new Berlin exhibition and accompanying publication pay homage to Daido Moriyama, one of Japan’s most groundbreaking photographers

“I and photography are one,” were the words of the Japanese post-war photographer Daido Moriyama. Credited with reinventing street photography in Japan, the 86-year-old’s retrospective at C/O Berlin and accompanying Prestel publication shed light on his radical approach to the medium. “The idea was to follow the transformation of his work throughout 60 years of production,” explains curator and editor of the publication, Thyago Nogueira. “The show reveals the evolution of his photography but also his provocative conception of the medium.”

Significantly, this is the first major exhibition to dig deeper into the Moriyama archives, tracing the roots of his oeuvre since the 1960s and early collaborations with Japanese photography magazines. Rarely seen examples of his contributions to subculture photobooks are on display alongside 250 works and large-scale installations. Bringing his non-conformist approach to photography into sharp focus, the show and exhibition publication reveal the frenetic spirit of Tokyo between the 1960s and 1980s – a time of rapid economic growth and political turmoil following developments in the diplomatic relationship between the US and Japan.

Amid the cultural transformation, Tokyo became a dynamic breeding ground for creative expression, particularly among a new generation of photographers. In 1961, Moriyama arrived in the city, following the footsteps of Shomei Tomatsu, who had established the short-lived Vivo Agency (Japan’s equivalent to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Magnum in Europe). But Moriyama would ultimately diverge from his mentor, forging his own path. He shunned modernist aesthetic principles and the idea that photography should attempt to capture reality. While Tomatsu veered towards realism and even social documentary, Moriyama spearheaded a dissident photographic practice, one adopting an embodied and intuitive approach to the medium. “He didn’t want to observe and communicate the world from his own subject perspective … his work is really about removing any pretentiousness, clichés, or didacticism,” explains Nogueira, who originally conceived the exhibition at Instituto Moreira Salles, Brazil, where he works as the head of the contemporary photography department.

The C/O show crucially displays Moriyama’s photographic works alongside his writing, adding a layer of depth to the photographer’s career by revealing his philosophical musings. “His writings have not been very accessible before,” says Nogueira. “He writes about the medium in a very interesting and intellectual way – it’s not merely an explanation but an investigation into the very nature of photography. He is asking: what is the essence of photography?”

In 1969, Moriyama produced a 12-part series with the magazine Asahi Camera. An example of ‘rensai’, translating into ‘serialisation’ – the practice allowed him to develop a project as a serial, in monthly chapters. Over the course of that year he developed the project Accidents: Premeditated or Not, in which he explored the dissemination of press images following the assassination of Robert F Kennedy. The series was not about death itself, but the role of media; the growing gap between real events and society’s consumption of images. Echoing Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967), Moriyama was also ruminating on an oversaturated image world, in which the mere appearance of reality takes on the same significance as reality itself. “All that was once directly lived has become mere representation,” Debord once wrote.

Even during the time of the Vietnam War, Moriyama refused to turn his lens towards the conflict, unlike his esteemed contemporaries such as Tomatsu and Ken Domon. Instead, he drew attention to the futility of photography. “He argued that we cannot attempt to represent tragedy through photography – the medium can’t truly grasp the reality of conflict. In this sense, he was always taking a step against the status quo of photography in Japan,” Nogueira says. “He didn’t want to follow the trends and he received a lot of criticism for that.”

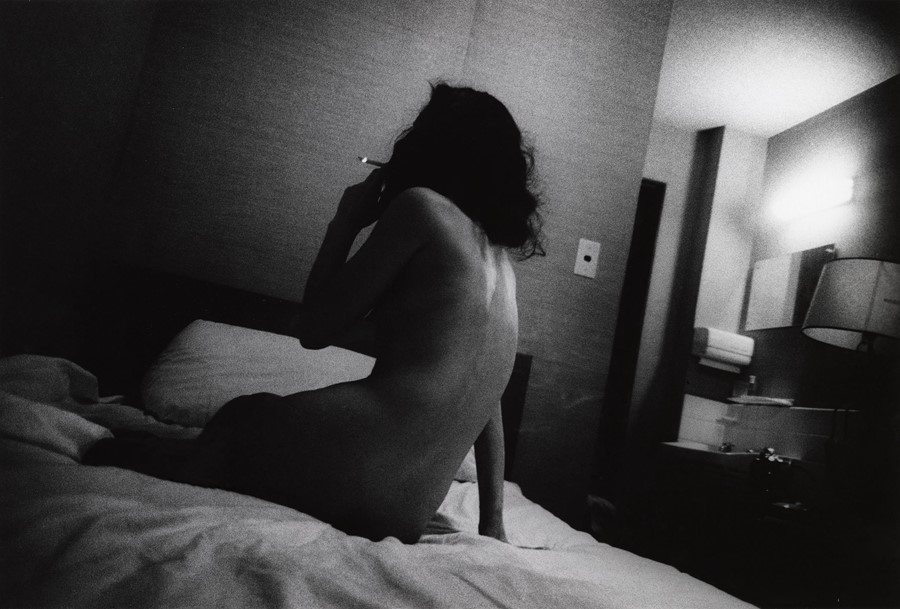

Moriyama’s philosophy on photography challenged both social reportage and the commercial hijacking of images in consumer and mass media culture – a by-product of Japan’s Westernisation in the post-war years and closer alliance with the US. In contrast, his street photography proposed a new visual language, one conveying the fleeting and fragmentary nature of reality. His photographic gaze was raw, immediate and even subversive – embracing what we might call ‘anti-aesthetic’. Grainy, blurry, and out of focus (translated from his mantra “are, bure, boke”) his works didn’t seek to flatter his surroundings. “Why must a photograph be focused? Why must a photograph be completely toned?” he once stated in an issue of Photo Art from 1967. “In short, the world, including me, is not beautiful at all, and therefore my photographs are not beautiful either.”

For Moriyama, photography should be a non-elitist medium. For that reason, he preferred to produce photographs for easy-to-distribute printed magazines, rather than the lofty walls of galleries or museums – institutions representing the establishment. This presented a challenge for the curators of the C/O show. “We had to question: how do we represent these works in a museum – which is designed for framed paintings on the wall – while Moriyama’s works and the debates around his photography were made for accessible printed publications?” says Nogueira. “Moriyama often said ‘photography must have a horizontal relationship to the world’. By that, he means that the artist shouldn’t position oneself in an elevated or privileged position – as if above society or as some kind of artist genius.”

In short, Moriyama regarded himself as indistinguishable from his photographs. He criticised his contemporaries who attempted to ‘capture’ reality from a critical distance. “They are on the outside of reality all the time. Even their bodies. And that’s why their photographs are, plain and simple, only representations.” So when you stand before a Moriyama photograph – beyond the initial indiscernibility of the image – you are shadowing his lived experience. You are stepping into his world, and viscerally comprehending his physical engagement with his surroundings.

Daido Moriyama is on show at C/O Berlin until 7 September 2023. Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is published by Prestel is out now.