“[It] makes me feel really good that I was able to transport people into a peaceful time, a different time of Ukraine,” says the photographer of her new book Odesa

In front of a leafy backdrop, a teenage girl stares just off shot at something in the distance. A young man rests his head on her shoulder, cooly fixing us with a gaze laden with a soft defiance. They’re in the southern Ukrainian city of Odessa. It’s 2016, just two years after Russia illegally annexed the nearby Crimean peninsula. Small letters on the girl’s shirt read “sometimes you find yourself in the middle of nowhere” and a tattoo on the boy’s collarbone states, “NO FUN.”

The cruel serendipity of these words can’t go unnoticed. It’s one that runs through the pages of Yelena Yemchuk’s photo book Odesa, parts of which are currently on show at the Ukrainian Museum in New York, alongside Yemchuk’s short film, Malanka. “I remember taking this picture,” Yemchuk recalls, cautious not to paint herself as something of a mystic. “I didn’t read what it said on her T-shirt. I had no idea [...] I just loved their faces. I took the picture. And when I look at that now, I mean, it’s so symbolic.”

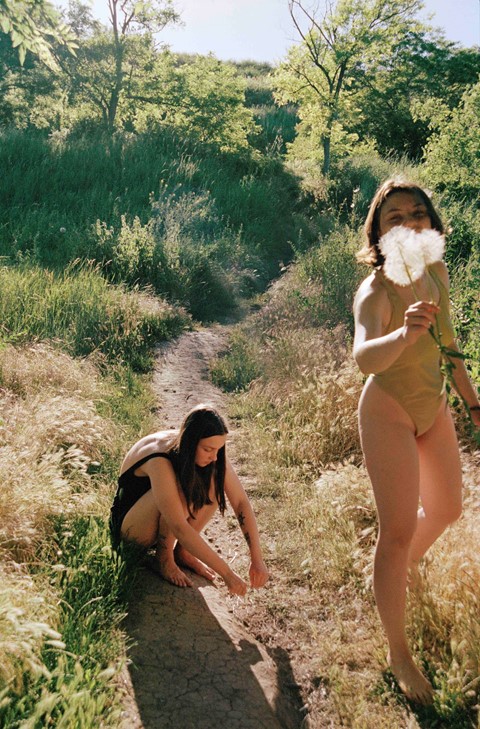

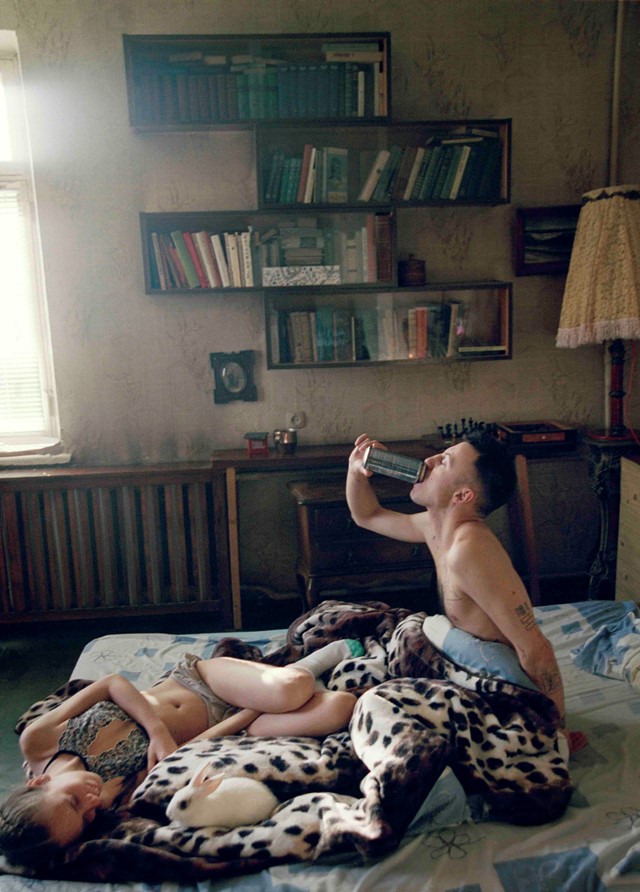

Part of her artistic process, Yemchuk explains, is to approach her subjects with an openness. This sense of openness can often pick up on a mood bubbling just under the surface of the everyday. “The older I get, the more I understand that the root of my creativity has really come from my homeland,” Yemchuk explains, discussing her move to the US at the age of 11. Much of her artistic projects based in her homeland are not the only evidence of what Yemchuk calls “a love affair” with her country. Odesa is fragranced with an ardent nostalgia, with the hazy memories of picking dandelions at your grandmother’s datcha. They evoke the aroma of a long summer’s evening, so savoured in lands where winter can feel like an eternity. It’s a nostalgia that many Ukrainians visiting her exhibition in New York are drawn in by. “Everyone that comes into the show just says, “Oh, my God, I miss Ukraine so much.” [It] makes me feel really good that I was able to transport people into a peaceful time, a different time of Ukraine.”

Although initially hesitant to release Odesa just a few months after Russia’s illegal invasion began, Yemchuk is happy she did. She’s determined that people see more than the images of bombed cities and war, but also the joyful and beautiful lives that predated the horror.

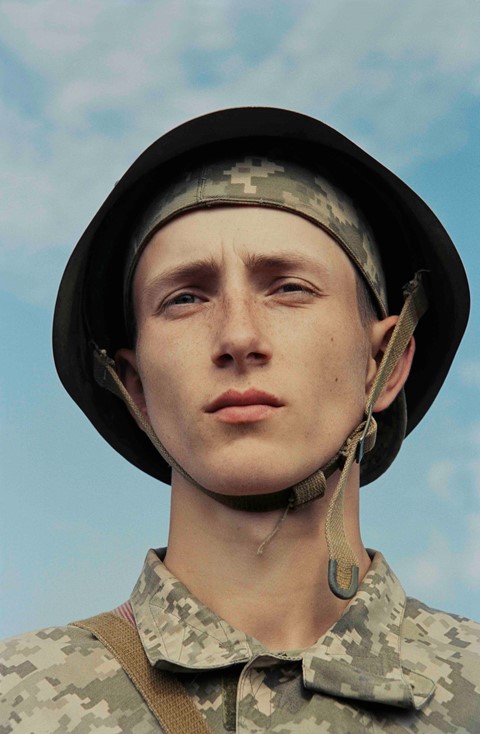

Still, an unease ripples through Yemuch’s photographs and film. The gazes of many of her young subjects are soulful, yet detached, with a sort of passionate melancholy that will be familiar to many Eastern Europeans. “It’s inherent in the land that I’m from,” Yemchuk says, discussing the history of many occupations, of Russian imperialism in Ukraine and the turmoil that followed independence in the 90s. “[Young people in Ukraine] just have a knowledge and an understanding of life much earlier than others do; they’ve seen a lot already.”

A sense of danger is also present in Yemchuk’s new film Malanka. It’s set in a rural Ukrainian town which is celebrating the pagan tradition of the same name, where, legend has it, the devil has captured the Earth’s daughter. Navigating masked creatures of the underworld, the townspeople yearn for her release and the beginning of spring. Yemchuk made the film before Russia’s invasion and acknowledges the shuddering relevance of its themes. The film’s protagonist searches fearfully, yearning to find a wayward ethereal beauty, played by Anna Domoshyana. “There’s so much in the film that makes me think of the situation now … Entering something dangerous, and trying something unknown, trying to get out.”

Yemchuk hopes that her work also portrays a beauty, a resilience and a strength that the world knows the young people in her images must now grip on to. “This generation is so fascinating to me because they’re the first generation that doesn’t want to be Soviet and doesn’t want to be western. They want to find their own way.”

That determination to carve out a place for themselves, even if it means unimaginable sacrifice, underpins Yemchuk’s confidence. “I know Ukraine will win. And I know we will rebuild. But it will just be different from now on. So I’m very happy that I documented this particular moment in time in Ukraine.”

Yelena Yemchuk at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City is on show until April 15.