For Sergei Pavlov, 2022 was filled with remarkable professional growth, from his first exhibition at the Lahti Museum of Visual Arts in Malva to the showcasing of his series Sea Songs at the 37th edition of Hyères Festival held at the Villa Noailles. Even so, having spent most of his time in the darkroom occupied with administrative work and planning, the Russian-Finnish photographer reached the end of the year satisfied yet at a certain impasse. “I was so drained. I felt that all these things to do with artistry, identity and oneself becoming a brand started to feel like chains, and I wanted to break that spell. I had this urge to go out,” he tells AnOther. “So what I did was book a ticket to Japan.”

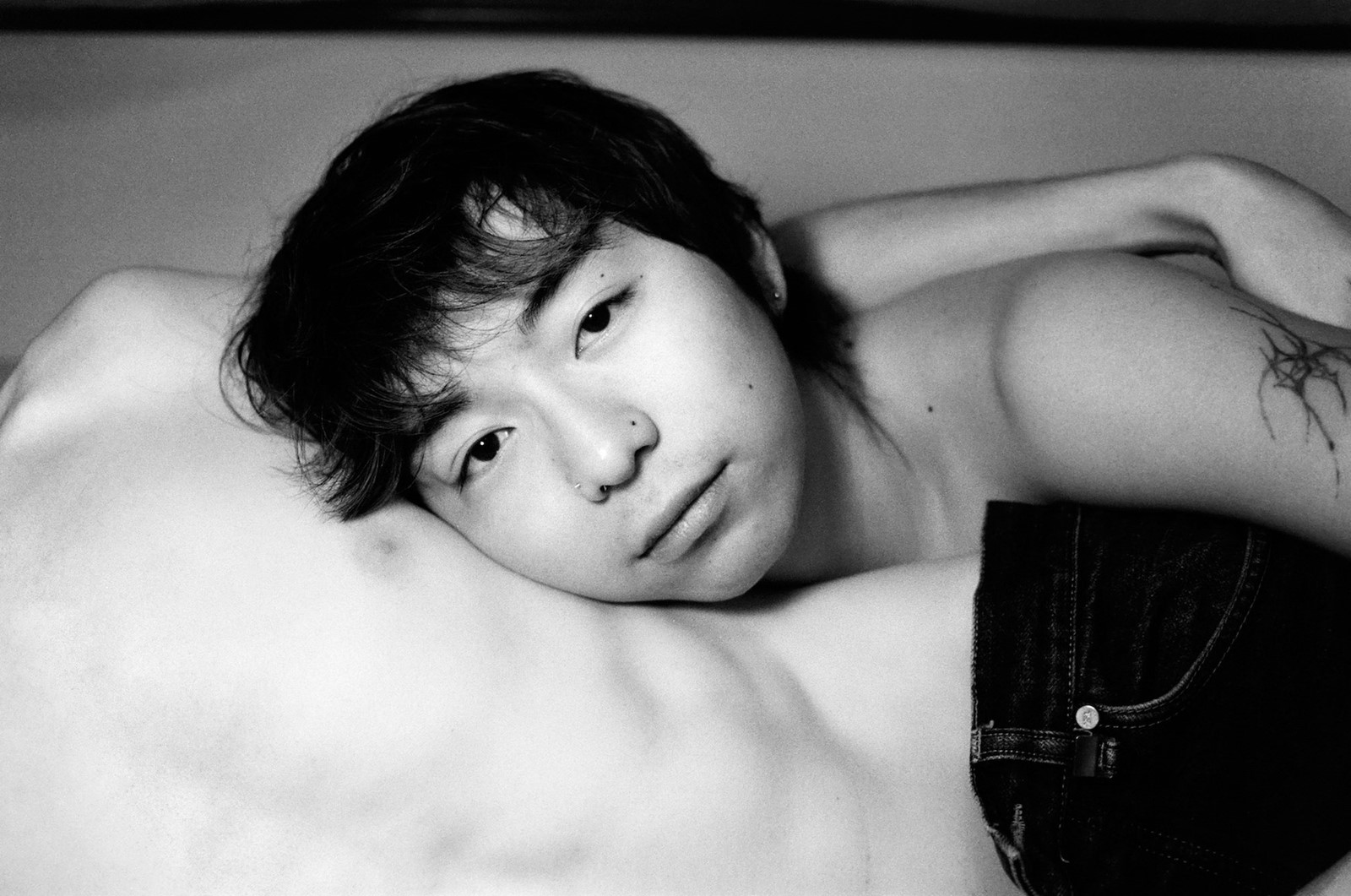

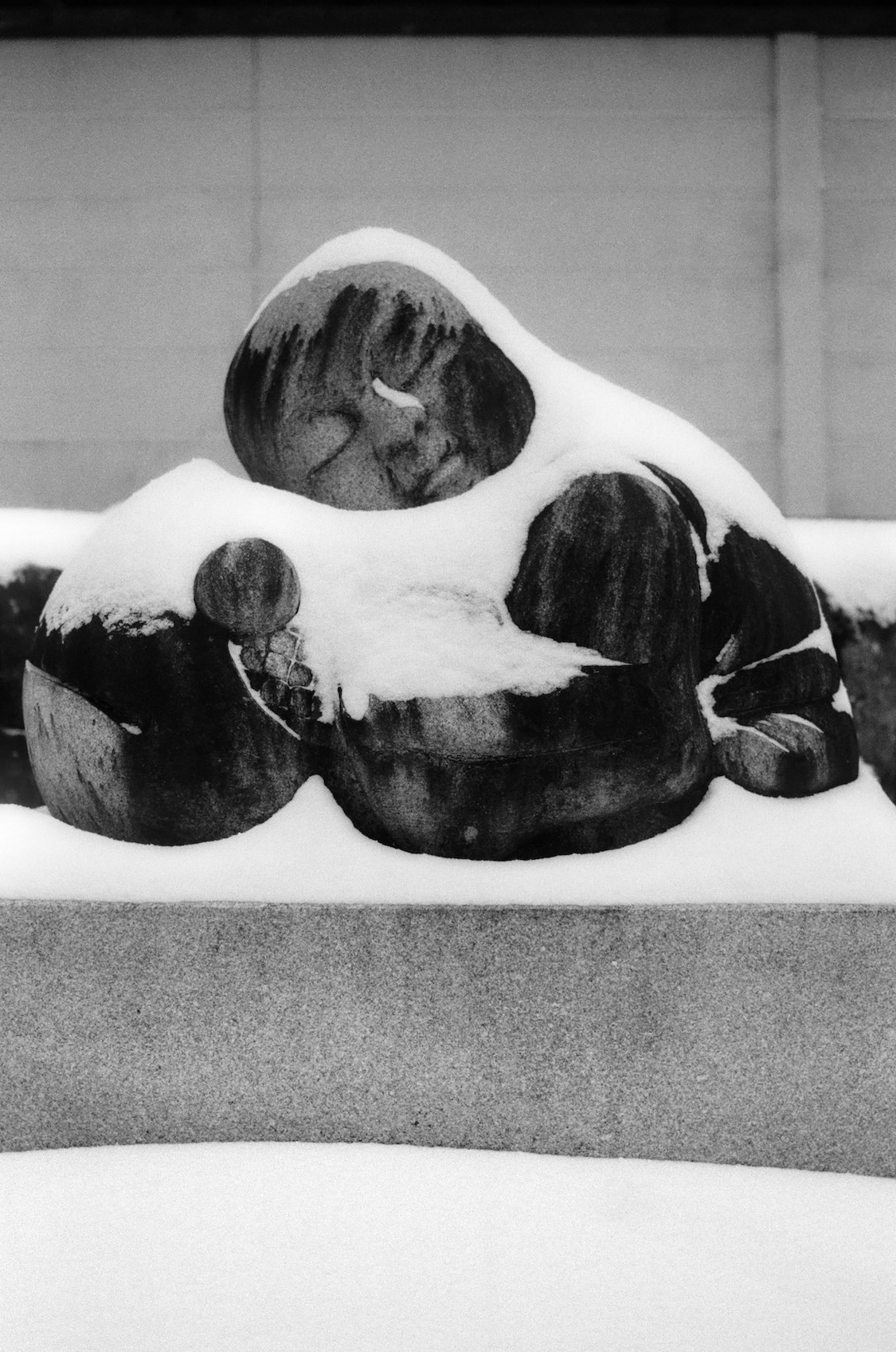

Reminiscent of Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation, Hello Japan chronicles Pavlov’s two-month-long journey through the country. In a delicate monochrome characteristic of Pavlov’s analogue approach, desolate stills of Japan’s snowy landscapes are placed between warmer portraits of different faces, naked bodies, and skin. As the project unfolds, Pavlov negotiates his own identity and sexuality while dissecting the dichotomy of desire and intimacy, and reflecting on themes of loneliness, belonging and love.

Here, speaking in his own words, Pavlov tells us more about his recent journey to Japan:

“I realised at customs they were going to ask ‘where are you staying?’ but I hadn’t booked a place. I didn’t have a plan – I tried to find accommodation but everything was booked. At that point I had been awake for 50 hours and suddenly everything was too much so I decided to go to Kyoto. There, I felt quite shit – I was completely alone for two weeks. I ended up at Koyasan, a Shingon Buddhist temple where I spent three days.

“On my last day, I fell into this lucid dream and realised I had one wish I could make, so I asked this old Tibetan teacher to come and tell me what the hell to do with this trip. I had thought it was going to be amazing but I had spent two weeks alone and depressed, looking at flights back home. [The monk] said to me, ‘Everything is in everything, you don’t have to look for anything.’ The next day I woke up in perfect ease and went back to Tokyo. I felt like there were so many possibilities that came because I didn’t have anything to achieve anymore. When you have nothing to achieve, you start seeing the everything in everything.

“It took three weeks to get comfortable with the discomfort, then there was this amazing integrity and confidence. It’s important to get lost, to get unsure and to be uncomfortable and awkward. I want to start working like that every year where I go for one or two months without any connection to a place, just my camera. It’s so healthy, it really resets you.

“I fell in love with two people in Japan. Through my interactions with these two people, their faces started to change. I photographed both of them and wrote my thesis during the trip that ended in the words: ‘Maybe my photographic work should be looked at as love. It is not only about what we see or can recognise on the surface of the image, the essence of the work might lie in how looking at the image makes us feel.’

“When we see love, we either see desire or intimacy or it’s mixed, but we don’t see them separately. Meeting those two people at the same time, one representing desire, the other intimacy, it was like someone gave me glasses and I could suddenly see the distinction between the two. My trip was very transformative, but the biggest change was this realisation of desire and intimacy.

“The photographs are all symbols. There’s staircases, there’s reflections, people together, people alone, there’s the beautiful bodies but then there’s the faces, the connections and the touch of the skin. It’s a cliche to say but it’s trying to understand how I relate to the world – what’s my place? I want people to look at the images and to feel at peace. It’s very important for me not to represent anything other than timeless, honest intimacy.

“There’s this Buddhist monk who said, ‘The Buddhist mantra is not “om mani padme hum”, it’s let go, let go, let go.’ So much of my trip was about letting go and being kind, not just to others, but to myself.”