In 1972, Lee Lozano left New York City and cut all art-world ties. A new exhibition in Turin aims to make sense of this mysterious artist, whose radical work criticised male-dominated power structures

When US painter and conceptual artist Lee Lozano announced her formal departure from the New York art world in 1972, nearly 30 years before her death, she did so in the only way she knew how: with a raised middle finger to the establishment she’d spent her entire career fighting. In her 1969 General Strike Piece, the work that precipitated her eventual dropout, Lozano detailed the conditions of her announcement. She stated that, in order for an art revolution to take place, a wider revolution, spanning science, politics, education, drugs and sex, was simultaneously required, while any reforms to museums must be met with comparable changes to galleries and magazines.

It’s perhaps no surprise then that Strike, Lozano’s new survey show at Turin’s Pinacoteca Agnelli – the first of its kind to be staged in Italy – opens with Lozano’s unceremonious farewell. Not only does General Strike Piece bear clear thematic connections to the exhibition’s title, it also epitomises the conflicts and contradictions that lie at the heart of Lozano’s under-recognised practice. Beginning with the fact the announcement was published in a magazine, the very media she sought to reform, Lozano didn’t stop making new work. Instead, she retreated to her Lower Manhattan loft studio and entered a particularly productive period of making work.

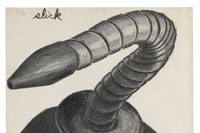

These contradictions are positioned front and centre in Strike, which succeeds in both shedding light on an artistic career that has at times teetered towards obscurity, while bringing it into dialogue with the industrial setting of the Pinacoteca Agnelli, Fiat’s former factory. In Lozano’s Tools series (1962-64) for example, pencil drawings of drills, hammers and other utensils initially appear as objective diagrams of inanimate objects, but quickly double as anthropomorphic forms in sexual motion (with a playful eroticism that fails to hide something darker). In one sense, these works evoke male-dominated production lines and in another, they subvert it, with bent nails and flaccid hammers robbed of their practical functions.

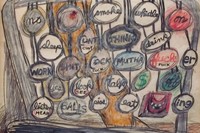

Throughout the early 1960s, Lozano would continue to use tools, labour and their relationship with the body as a critique of male-dominated power structures. In her sardonic 1962 painting No title, for example, a gloved hand holding a coin inscribed with the word ‘Liberty’ moves towards the nude form of an anonymous female figure, her genitals replaced with a dark coin slot. Later, in her more minimalist series of large-scale oil paintings, Lozano shifts towards more abstract and geometric forms that she planned with mathematical precision. All named after verbs, including Cleave, Hack, Split and Peel, they hint at destroying systems of control, both in the art world and that of capitalist labour.

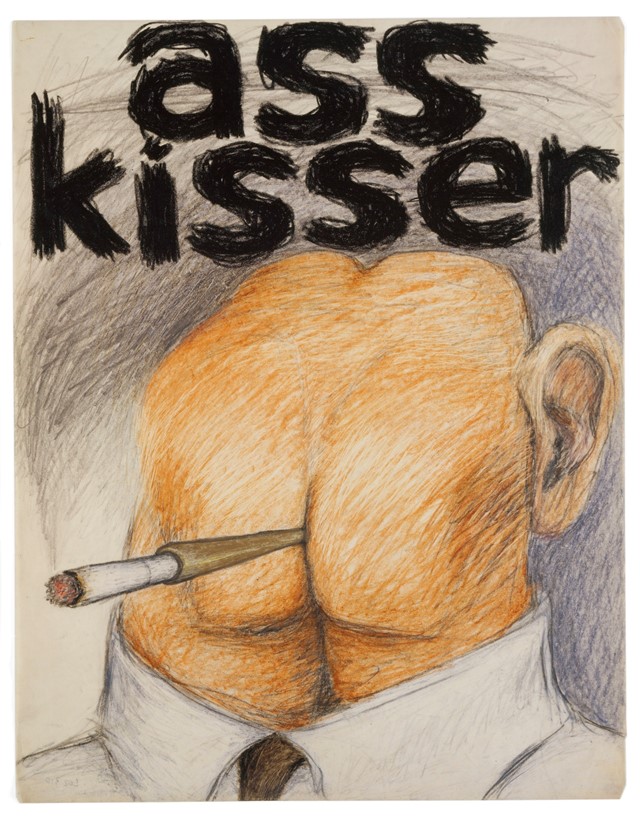

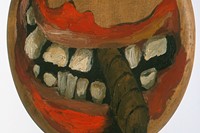

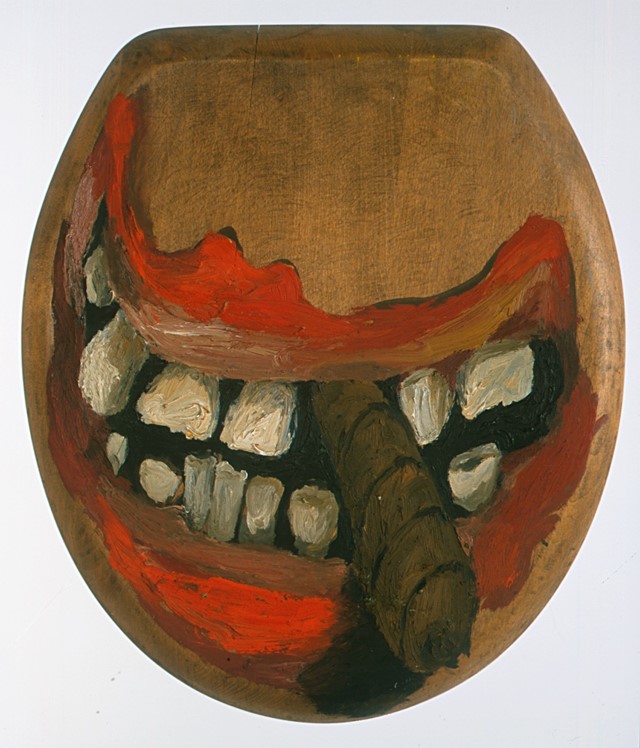

Lozano was never one to shy from innuendo or titillation, and her acerbic wit punctures this exhibition at regular intervals; nowhere more so than in a room dedicated to her love of puns, in which she combines pornographic images with advertising jargon to create fiercely satirical works that ring with Lozano’s signature brand of radical individualism. In works like Ass kisser (1962) – a man’s face replaced with a naked bottom, cigarette clasped between its cheeks – Lozano reflects the feminist energy that was gathering pace during the 60s, without ever pledging her direct allegiance. In 1971, as a result of her increasingly fraught relationship with the women’s movement, Lozano went as far as boycotting her relationships with women entirely, an unofficial strike action that was only meant to last six months but ultimately only added to the growing isolation that defined her later years.

To say Lee Lozano marched to the beat of her own drum is putting it mildly, but often her radical commitment came at a personal cost. By the time she had cut all ties with the art world and its institutions, Lozano had retreated into a world of her own making, one increasingly defined by her various acts of refusal and rejection. During this time she compiled lists and notebooks, one of which detailed the extent of her isolation: “NO telephone, radio, records, reading, drugs, visitors, mail, window view, clock.” This unshakeable commitment to her principles, combined with her determined effort not to be siloed into any artistic category, detracted from the recognition she received over her lifetime. Yet, 50 years on, it is also what gives her legacy such enigma and enduring appeal.

Strike by Lee Lozano is on show at Pinacoteca Agnelli in Turin until 23 July 2023.