A new book chronicles Ruth Bernhard’s remarkable 40-year career. “Men photograph a female nude as if she belonged to them. I photograph a woman as part of the universe,” she said

When we contemplate the history of photography – and in particular, women photographers who left their mark on the 20th century – names such as Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham and Dorothea Lange may spring to mind. A lesser-known figure who hasn’t received adequate recognition is Ruth Bernhard (1905–2006), a German-born photographer who made it her mission to radically transform the representation of women in high-art photography. “Men photograph a female nude as if she belonged to them. I photograph a woman as part of the universe,” she once said.

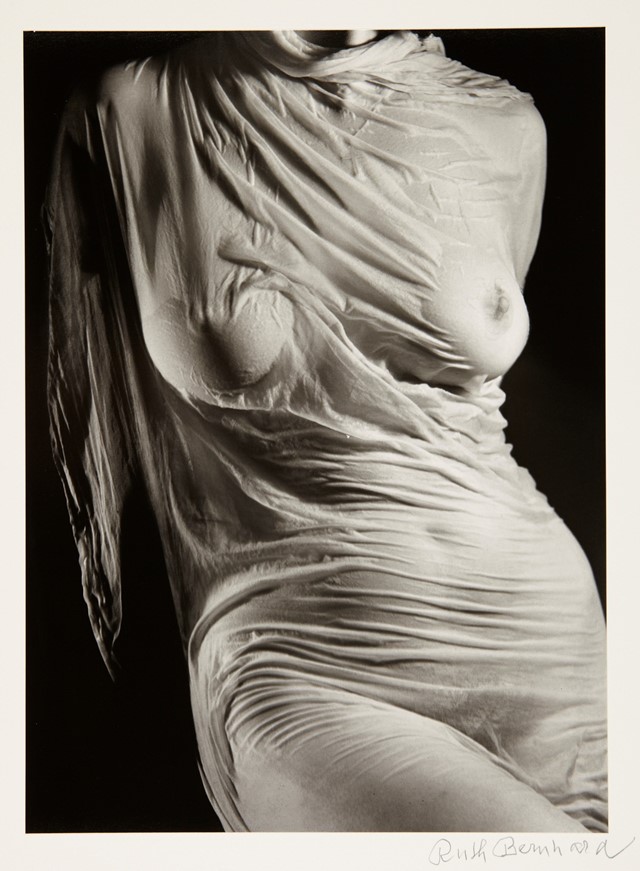

Ruth Bernhard: Photographies 1930-1976, published by Wasmuth & Zohlen, traces the artist’s 40-year career as she emigrated from Germany to the West Coast of the US between the wars. Revealing her lustrous meditations on beauty and light, Bernhard’s virtuoso studio photographs liberated both the female form and gaze. “No question, in her composition Ruth Bernhard emancipates herself decisively from tested patterns and distances herself from what often is described as the ‘male gaze’”, says Hans-Michael Koetzle, editor of the book.

As a German-Jew with a fraught family history, Bernhard’s oeuvre is arguably an expression of her psychological interior. When her mother abandoned the family in 1907, Bernhard’s busy father – unable to adjust to single parenthood – sent her away, to live with another family. “I was an unwanted child. All the things that I do and have done are the result of not having any parents. All my work is somehow related to that deprivation,” she said.

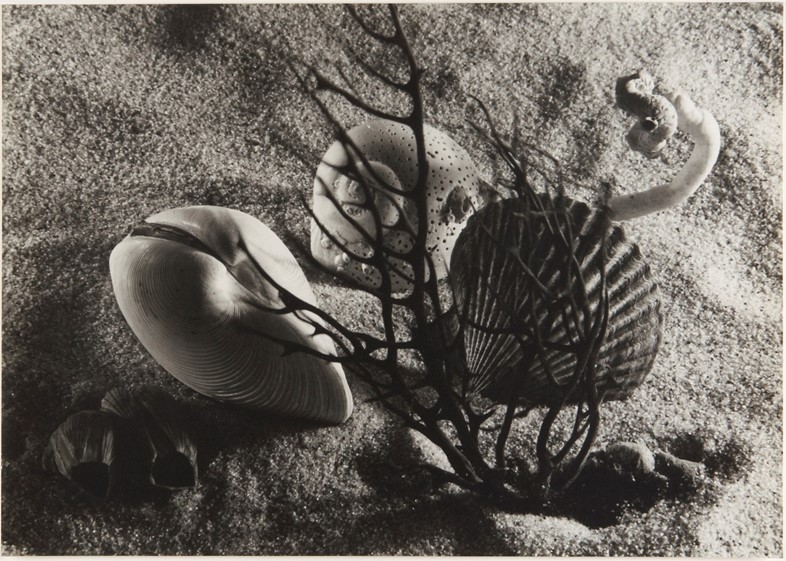

The new family’s house was a menagerie, a “veritable zoo” according to the book. She lived among more animals than people (canaries, reptiles, and rabbits). Her comfort in and fascination with nature would manifest in her early photographic work. “I have always identified and connected with nature and natural objects, and I feel that I know what it is like to be an animal.”

Carefully composed, her photographic arrangements – whether of animals, seashells, organic forms, or women’s bodies – reveal a reverence for the aesthetic principles of the New Objectivity movement, but also the artist’s poetic worldview, one which affirms the beauty of the world. “The ground we walk on, the plants and creatures, the clouds above constantly dissolving into new formations – each gift of nature possesses its own radiant energy, bound together by cosmic harmony,” she said.

In 1935 Bernhard became a US citizen, and the following year she moved to Los Angeles where she opened a commercial photography studio. Not long before, in a fortunate twist of fate she met the photographer Edward Weston while walking on a beach in Santa Monica. Although she still spoke little English, the two formed a close relationship, one that would last until his death in 1958. Upon being introduced to Weston’s work, Bernhard admitted, “It was overwhelming. It was lightning in darkness. It was not visual alone. It was an experience that encompassed and engulfed my whole being.”

As Koetzle tells AnOther, the relationship between the two photographers “must have been a close, fruitful, possibly intimate relationship”, though generally speaking, her name doesn’t appear in any of the ample literature on Weston, whereas his influence constantly hovers over her name. Although undeniably influenced by Weston, she photographed without strict recourse to particular avant-garde movements. She photographed intuitively. “I had no notion of how a photograph should be made or should look, or that there were certain things that ‘couldn’t be done’”, she said. “I did as I pleased, and I made pictures only of things that held my personal feelings.”

But it would be Bernhard’s unique meditations on the female body – in particular the female nude – that would earn her critical examination as an artist. Margaretta K Mitchell, the leading expert on Bernhard, recalls the moment she first shifted to this subject. “One day, a dancer was visiting and Bernhard invited her to pose. She complied by curling up in the shiny, cold, curved interior of the bowl. Bernhard thus made her first exposure of the nude.”

By capturing the nude with gravitas rather than eroticism, Bernhard’s portraits – principally concerned with compositional elegance – take on a sculptural quality. Beyond capturing the curves and sinews of the female form, light would also be her guiding force: “Light is my inspiration, my paint and brush.”

As a woman artist, a lesbian, a German, and a Jew, Bernhard’s distinct photographic vision came into existence against an increasingly hostile historical backdrop. Yet the revelation that her perspective could reframe and reclaim the female body from a patriarchal worldview, would spur the artist for the rest of her life until her death in 2006, at the age of 101. Her photographs reflect a rich and deeply felt outlook on the world, one that immerses viewers into her wondrously curious universe.

Ruth Bernhard: Photographies 1930-1976 is published by Wasmuth & Zohlen and is out now.