Each queer person’s story treads a different, formative path of self-exploration. While an urgency to express one’s gender or sexuality can sometimes meet an impasse with one’s own social and familial circle’s less accepting beliefs, an abstract bond can be tethered with others who share the experience – a new, chosen family, fostered by harsh coming-of-age trauma. Such is the case with Daniel Jack Lyons, whose commanding, sensitive photo series Friends of Valentine captures a chosen family of their own making in Los Angeles, barely on the cusp of formation. “So much of my work is about celebrating community and chosen family, being a queer person myself,” the photographer says. “You know, I literally would not be alive without my chosen family, without my community.”

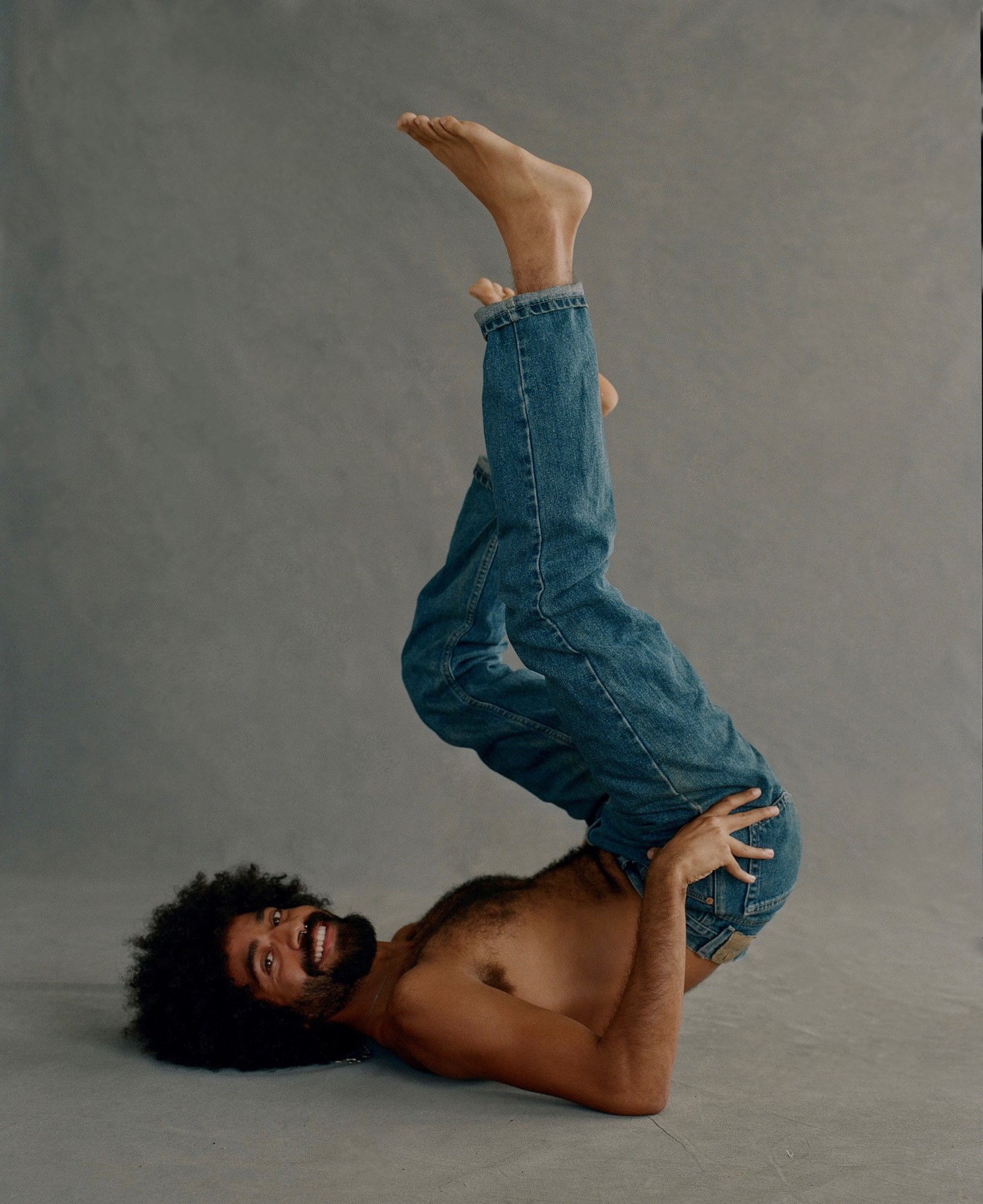

It’s coincidental that we speak on Valentine’s Day, almost exactly one year after they first met Valentine, a first-generation Mexican rising star in the modelling world, to capture some portraits for their own portfolio. Not long after their first meeting, Valentine and Lyons decided to reconnect in a photo studio for a follow-up shoot, both bringing with them their closest friends in a merging of their chosen families. “We created this little mini party. It was kind of like an exchange of sorts, and I just fell in love with their friends,“ says Lyons. “What often comes up in my work is this celebratory aspect, and this was about isolating that feeling from context, and doing a studio portrait of just family and connection.”

Much of Lyons’ practice revolves around lensing those they feel a sense of kinship with. “I think that sometimes people see my positionality, or my whiteness, or my name, and think like, ‘Oh, this guy just went into this place and photographed these people, and now he’s gone,’” they say over a Zoom call from their home in LA. “They don’t understand that the people who appear in my photos are my friends. They are people I spend time with, that I’ve had deep conversations with, and I’ve already established a level of rapport before a camera even comes out.”

Lyons spent years working at the crux of public health and human rights as a consulting anthropologist, travelling to developing countries such as Liberia, Rwanda, Brazil, Mozambique, Kenya and Sierra Leone to name a few. Hired to carry out a unique form of research called Photovoice, which uses participants’ photography to guide interviews, in turn overcoming a number of cultural and linguistic barriers, the data was passed onto the UN for their records – yet Lyons witnessed on the ground the participants had captured a singular, often beautiful series of images that distil a powerful lived experience. “I was hired to do that with Ebola survivors, with elderly people who were dislocated in Fukushima and Japan, and the discussion becomes: how do we utilise this? Who needs to see these stories?” Through placing the camera in the hands of others, the true power of photography started to manifest. “I started realising that my own experiences, and my own stories, and my own photographs are just as valid, and that led me to sharing my photos more, putting them forward to exhibitions, group shows.”

Lyon’s own photographic work started while in high school. “The photography teacher was an old hippie, and he used to let me get stoned in the dark room and stay there for hours.” Without the financial support of their parents, Lyon’s high school portfolio led them to securing an arts scholarship for college, where amidst the cultural backdrop of the 9/11 attacks and their own realisations of their queerness, they soon switched to a social behavioural science course. Using their camera as a tool for activism, Lyons began documenting the work of a radical local organisation called Gay Shame. “I was also realising my own positionality in the world and how I experienced homophobia, in the ways that I’m limited, and in the ways that I’m privileged. All of that conflated, and I had this global perspective – this very local community perspective of my queerness within the larger picture of US imperialism and racism.”

Their most recent photo book released in 2021, Like a River, lenses the coming-of-age queer inhabitants of a marginalised community in the heart of the Amazon rainforest – many of whom lived in one clandestine house run by a matriarchal drag queen, open to queer refugees who have been disowned by their own families. Early in their photography career in 2014, they began to photograph artists and young queer people who had been displaced by the invasion of Crimea, immortalising their resilience and bravery. “The thing that I find more astonishing is how similar we all connect. As a queer person, it’s almost like a superpower, in the sense that you can when you connect with another queer person – of course, culture is important and context is important – but there’s often this kind of connection of shared trauma in a way. Having to navigate coming out in whatever culture you’re in … it can be complicated.”

By finding themselves in the subjects they lens, Lyons dismantles the usual power dynamics between the anonymous-yet-authoritative photographer and the obedient model – in turn unleashing a radiating intimacy and a rare sense of queer joy, underrepresented in a time where hate crimes against queer individuals are rising. The complexities of ‘feeling seen’ authentically demands a certain level of bravery, and while the gender identities in Friends of Valentine vary, they unite in their fearlessness, spirit, and love for one another. “There were times when I was homeless, and my people have helped me. I find that extreme kind of affection, and that radical love is found with queer families in every culture that I find them.”