With work by Campbell Addy, Nadine Ijwere and Ronan McKenzie included, Aida Amoako’s new book is an “artistic archive on the myriad Black experiences of the late 20th and early 21st centuries”

London-based arts and cultural writer Aida Amoako has lent a careful, critical eye towards a variety of subjects – everything from the history of the colour yellow to the influence of hardboiled crime and noir on Michael Jackson’s Smooth Criminal – to unearth fascinating insights on how our collective imagination is constructed through art, media and technology. At heart is an abiding interest in how mythologies “trickle down and are expressed in the cultural products of an age.” With As We See It: Artists Redefining Black Identity, published by Laurence King, Amoako offers a refreshingly expansive reflection on the Black visual renaissance of late through an “artistic archive on the myriad Black experiences of the late 20th and early 21st centuries”.

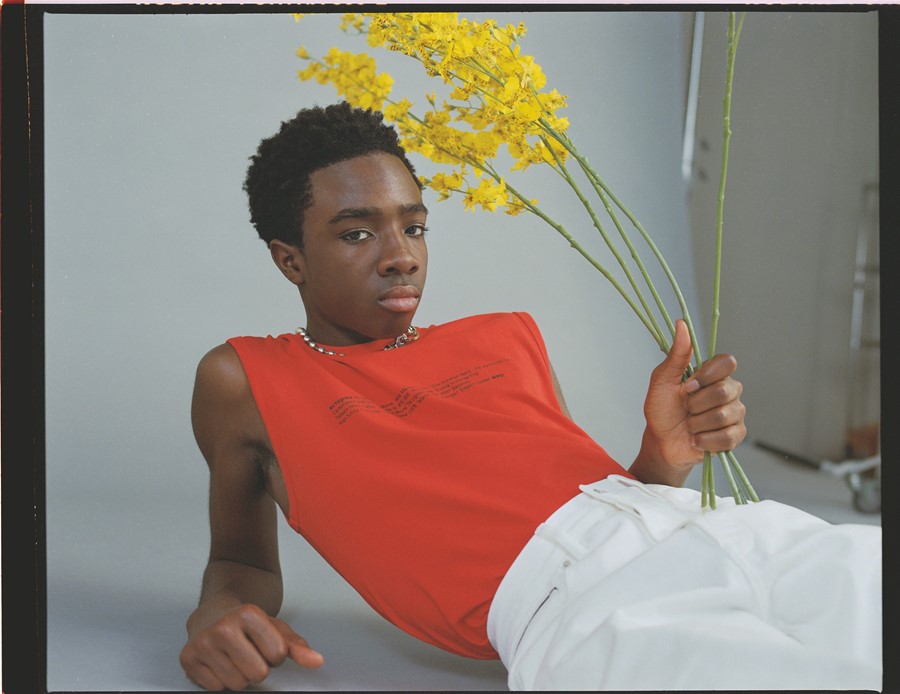

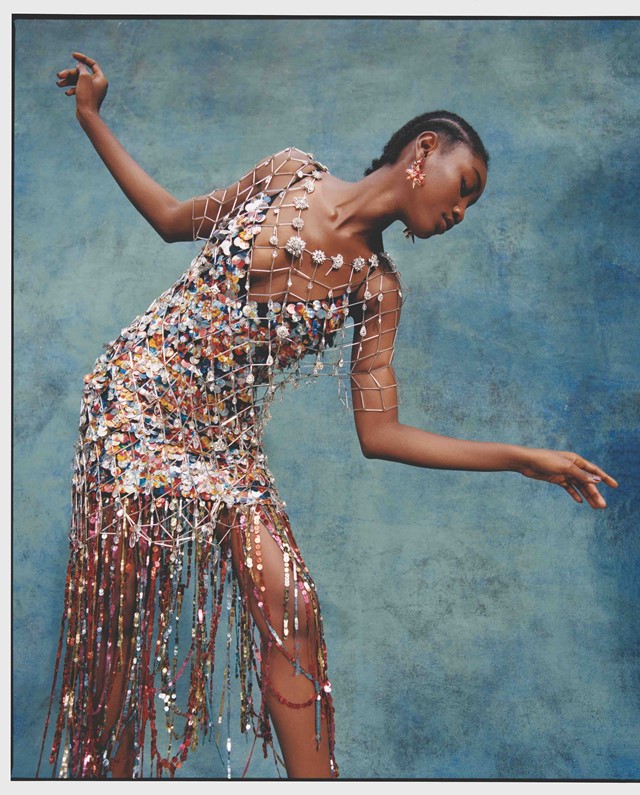

The book’s jacket image features a young Black man holding a Black boy in his arms. The pair are sheathed in Issey Miyake pleated jackets, sumptuous and black. Their gaze is steady and calm, the vulnerability in their eyes searingly beautiful. The image is by Paris-based photographer and stylist Kenny Germé, from his series titled The Godfather (2020). Germé is one of 30 image-makers featured in As We See It, which includes works by Campbell Addy, Girma Berta, Sedrick Chisom, Nadine Ijwere, Ronan McKenzie and Lina Iris Viktor. Germé, like many of the artists within the book’s pages, uses fashion and fantasy to reinterpret and subvert negative depictions of Blackness.

In putting As We See It together, which spans photography, sculpture and painting, Amoako drew inspiration from recent publications that investigate the complex relationship between the circulation of images, Black identity and performance: Feminist theorist Tina Campt’s A Black Gaze, influential curator and gallerist Antwaun Sargent’s The New Black Vanguard and writer Ekow Eshun’s far-reaching anthology Africa State of Mind. “I definitely wanted to break out of the Anglo-American perspective that dominates,” says Amoako. “I looked at artists from all over the world, all over the Black diaspora: Australia, Bahamas, Nigeria, South Africa. The whole project [was about] broadening perspectives and looking at blackness with all its multiplicity, so it made sense to go really wide.”

Amoako doesn’t name the 30 artists included as part of a movement or even generation per se, but points to an emerging “climate” fought for and cultivated, a flourishing “in which Black artists have a much more prominent voice at a much younger age than many of their artistic predecessors.” Amoako points to social media platforms like Instagram and Tumblr that have “allowed people to get a platform much quicker, at a much younger age than they would have in the past.” “It’s also allowed a great level of lateral networking across great distances,” Amoako explains. “Gatekeepers fetishise youth and these artists have managed to grab people’s attention in a way that is more meaningful and has more sticking power than: ‘here’s a group of Black artists because we’re doing something spicy today.’”

Notably, these artists are keenly aware of and pay homage to their artistic elders – Malick Sidibé, Carrie Mae Weems, Gordon Parks and James Barnor to name a few – without being beholden to them. “It’s one of the things I admire in the artists, the idea of those giants of the past [being] jumping-off points rather than gods that must be worshipped,” says Amoako. “It’s not a ‘boo-boomers’ kind of thing. There’s definitely a great respect there, but there’s also a fearlessness about creating and not worrying about old gatekeepers and or comparison that other generations might have been concerned with because they were trying to break through a pretty thick glass ceiling,” Amoako explains.

In the book’s introduction, Amoako proposes the prefix “re” as a theoretical framework. Amoako arrived at the prefix by “reading interviews and essays that the artists themselves had given,” she says. Words like “reimagine, reconsider, reconceptualise, reread and rework” reoccurred. “I thought it was really interesting, this idea of trying to remind people of the malleability of something,” says Amoako. “The idea of defining something that connotes the opposite of permanence but without that idea of something being in flux undermining anything. To say Blackness is always in flux does not undermine the power of the idea of Blackness. There’s a song that Braylon Dion cites, ‘No ruler can size you,’ and that’s what these artists embody and what that constant ‘re’ means.”

Fittingly, the feeling of multiplicity, of flow, permeates As We See It. The works within happily feel like provocations – places to begin, not end, portals to imagination and possibility. “It’s not just about presenting counter-narratives through photographs,” Amoako offers. “It’s about emphasising that any photo is just the beginning, the entry point, and the wealth of emotion, artistry, humanity you encounter in the photos is just the tip of the iceberg.”

As We See It: Artists Redefining Black Identity by Aida Amoako is published by Laurence King and is out now.