“Life is fascinating,” says Collier Schorr down the phone, when asked how she’s doing. The photographer – who shot Dakota Johnson and Zoë Kravitz for the cover of this magazine – is known not just for her fashion photography but for her decade-spanning art practice, which intertwines themes of history, nationality, fantasy, gender and identity. Throughout our call, we discuss the intensity of Schorr’s most recent romantic relationships as well as the self-interrogation they set into motion. Schorr jumps right in; this makes photography the perfect profession, she half-jokes, “because it’s like a sanctioned form of promiscuity. I can be with a different person every day, watching them move … if you’re the kind of person who thrives on intimacy – which I am – you have this beautiful time with people and get to know someone very quickly. You’re like ‘wow’, and then they’re gone – that’s photography in its most magical, transgressive space.”

It was a love affair that led Schorr to the small town of Schwäbisch Gmünd in southern Germany during the 1990s to shoot some of her most famous photographs, most recently captured in the book August, published this summer by Mack. Schorr had seen a photograph of the legendary punk Edwige Belmore in Andy Warhol’s Exposures when she was at college in 1981 – “I couldn’t figure out if they were a man or a woman and there was no Google at the time, so there was no way of working out who someone was”. By chance, Schorr soon found herself working on a friend’s film set where Belmore was the star, and the two met and ended up living together. “Later, I was helping Edwige’s ex-girlfriend bring a few things back to New York from Germany and while we were there, we went to a cafe.” There, Schorr met her soon-to-be long-term German girlfriend – “I fell in love, and that was it.”

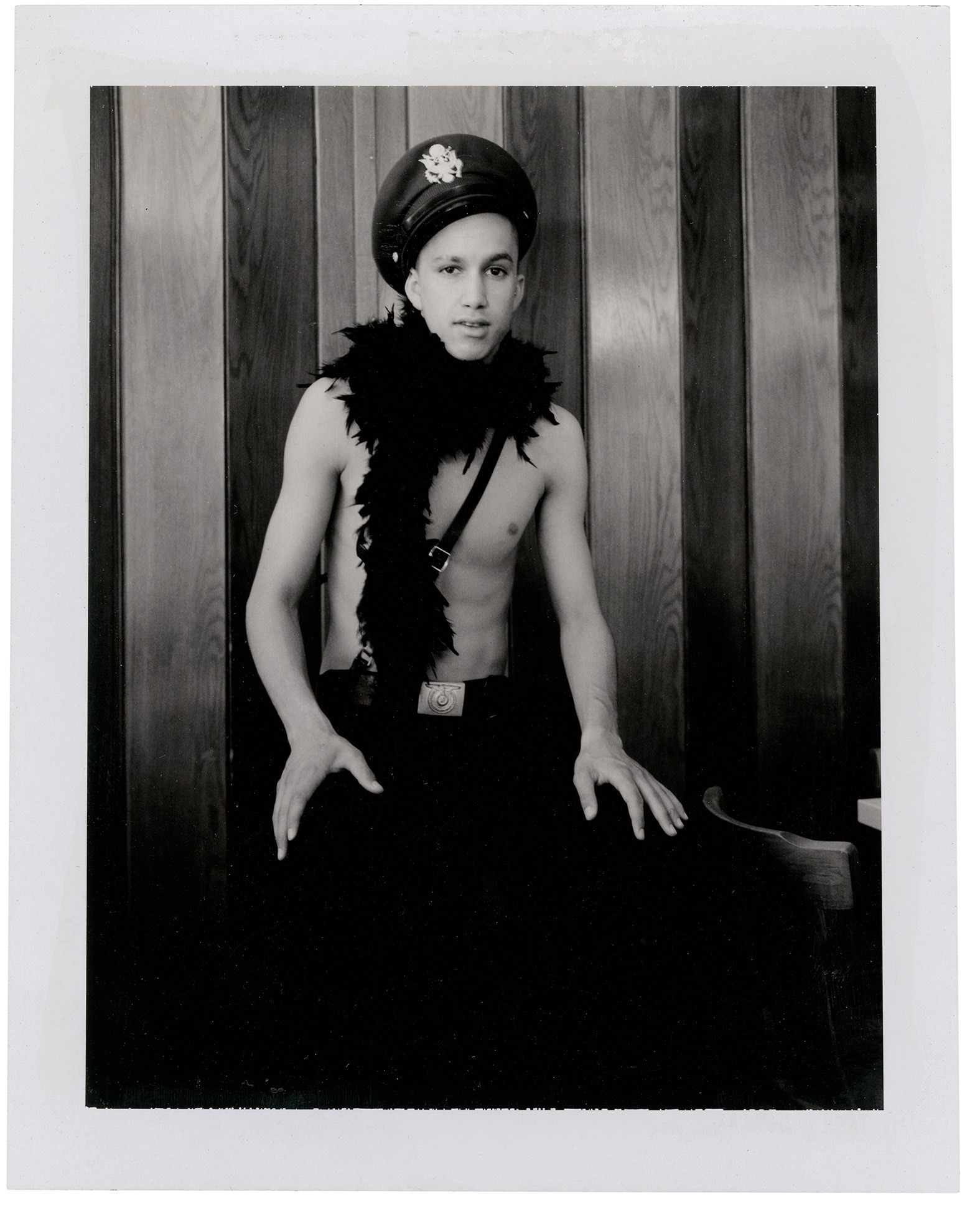

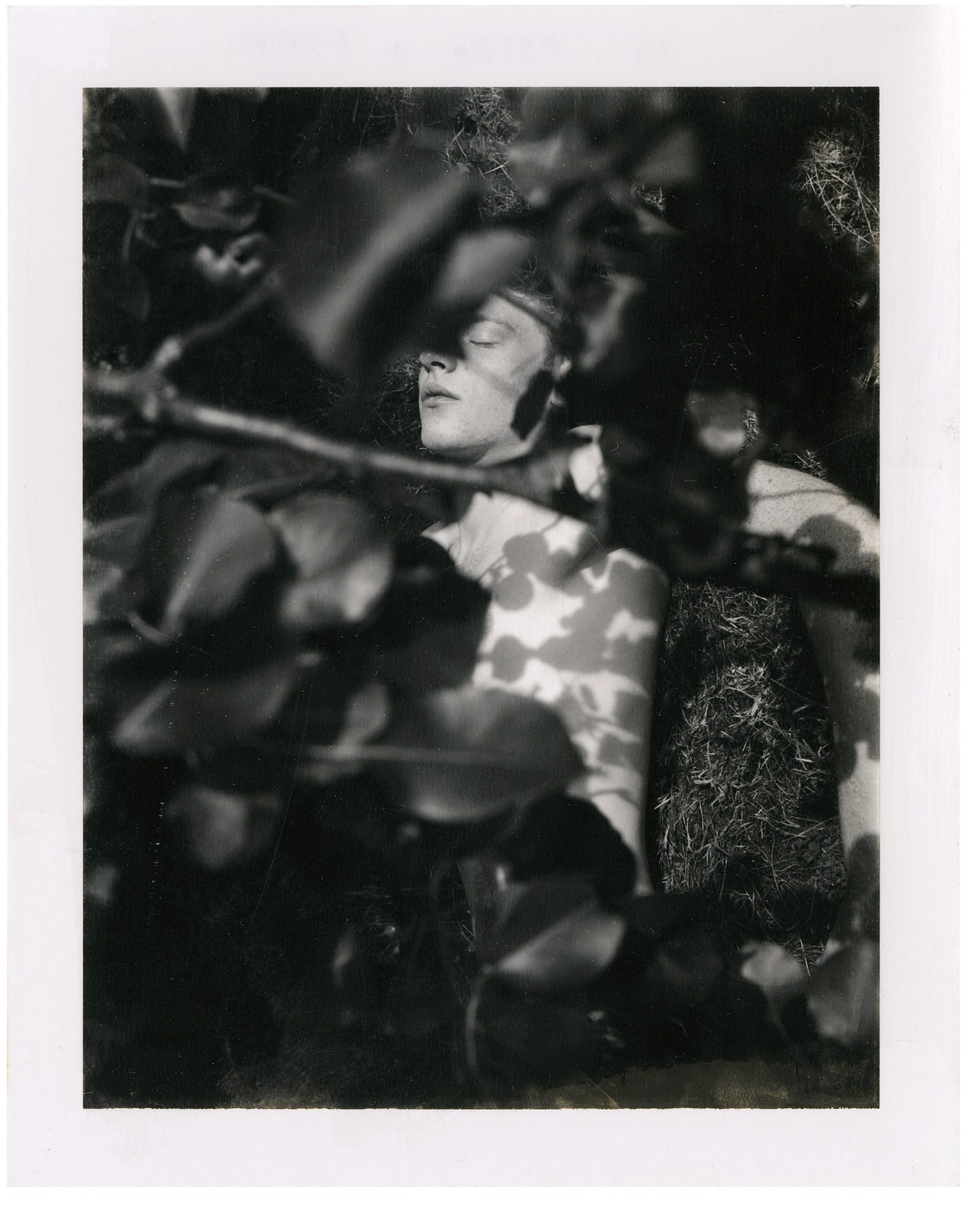

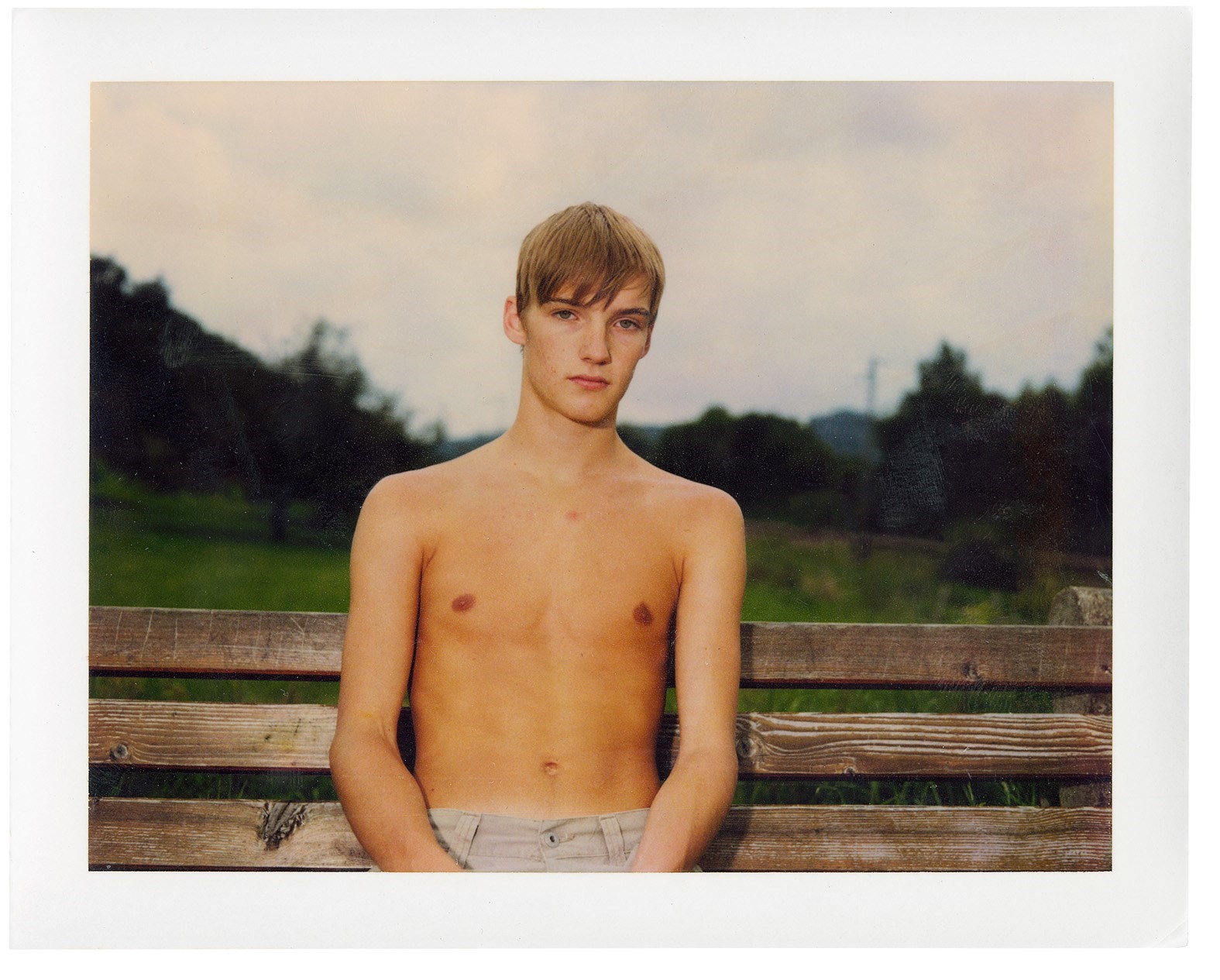

Returning to Schwäbisch Gmünd each summer, Schorr photographed still lifes – such as the flowers seen in her previous book Blumen (published in 2001) – as well as locals, also captured in her book Neighbours Nachbarn (2006). August, the third book in the series, is exclusively made up of polaroids of still lifes and adolescents, and blends together travel photography, war photography, anthropology and portrait photography. Unlike the passing interactions on a fashion set, Schorr got to know her models in August over time: “Some of those people I knew for ten years, they became part of a theatre troupe – it’s casting people or seeing a character and engaging with them. Each summer they would grow a little bit, but mostly they were boys and children so my feelings were less about intimacy and more about curiosity.” The curiosity stemmed, in part, from gender dynamics, says Schorr: “I have always seen a boy’s chest as a built-in shield and that they operate in the world in this very free way because they’re shielded or protected. I know nothing about that because I’ve always seen my body as incredibly vulnerable and something to cover.” Yet, “upping the ante” when it came to curiosity “was the fact that this was Germany” which, she says, “feels like its always been at war, to me.”

“I felt such entitlement in Germany, like I was allowed to do whatever I wanted because historically my people were so hurt – as though I was in the land of apology” – Collier Schorr

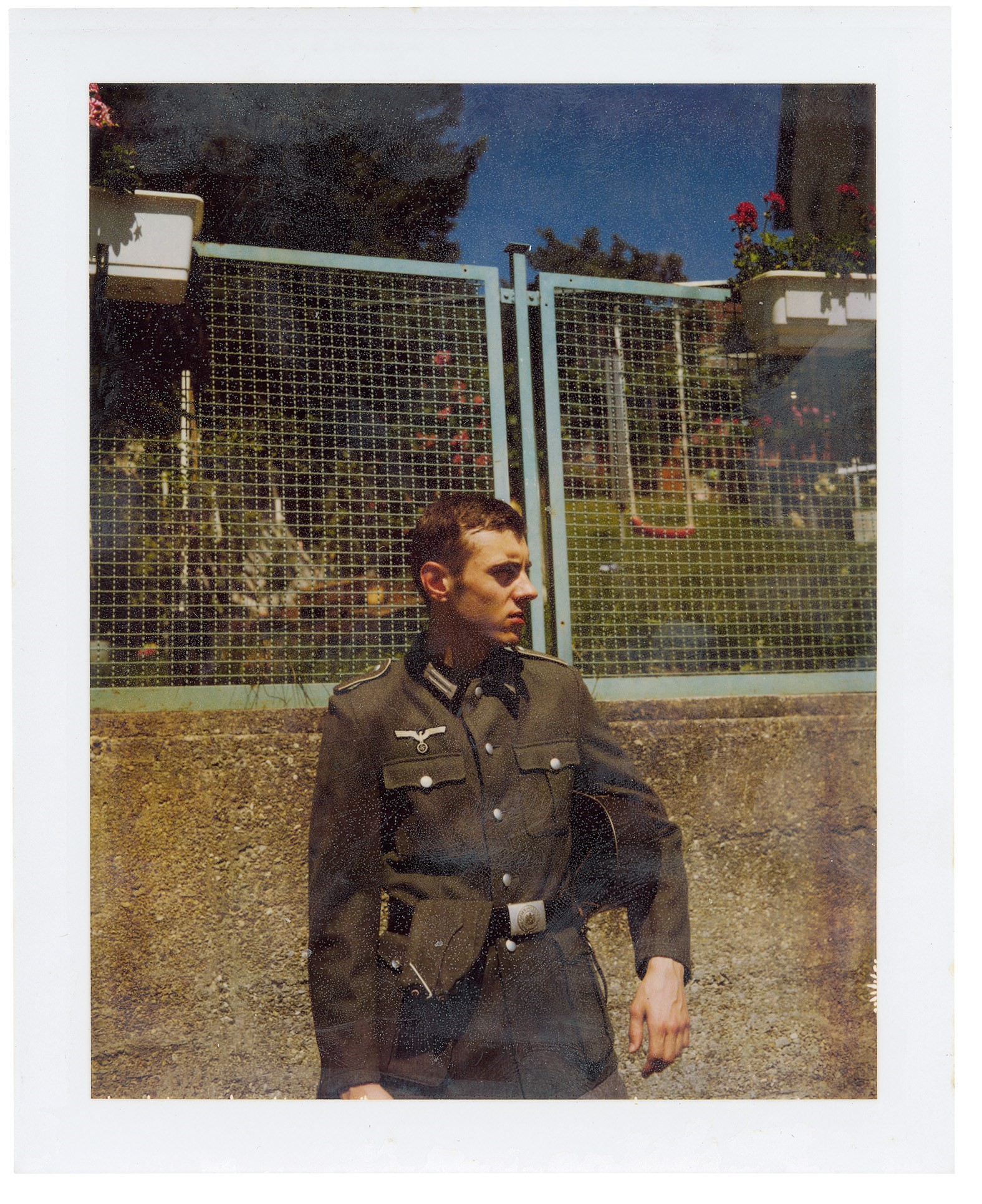

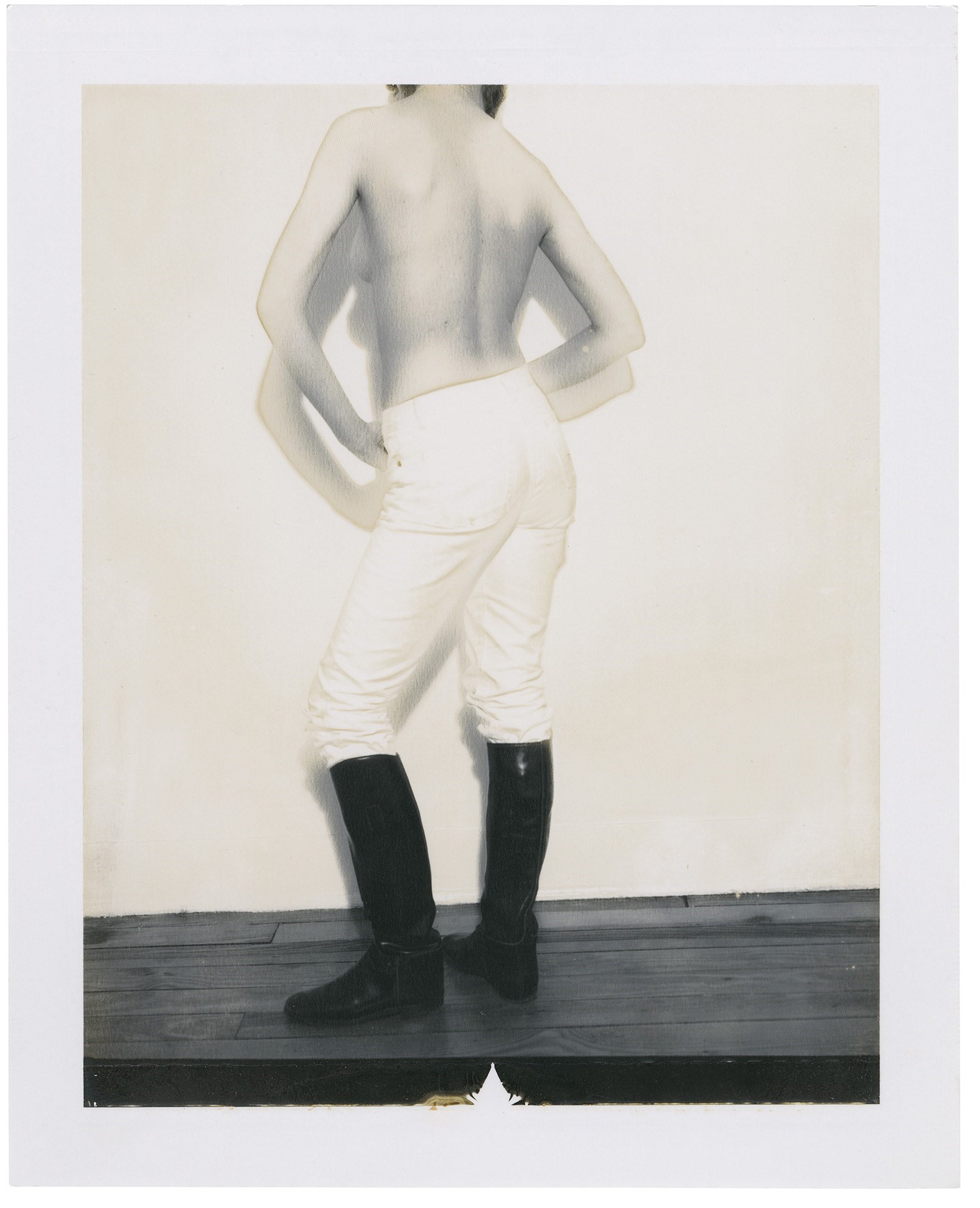

As a young Jewish queer person, part of Schorr’s relationship with Schwäbisch Gmünd was about trying to make sense of German history. In some of the images in August, Schorr dresses her subjects in German army uniforms sourced from costume or fetish shops in Berlin, sometimes with Nazi insignia. A power play pronounces itself, with Schorr reclaiming her power through the female gaze and as a Jewish person who felt like “the only Jew in town and the only queer in town” and yet “both invisible and safe” as she captured her subjects.

“I had so many preconceived notions about Germany growing up as a Jewish kid in New York, in Long Island and New Jersey, and watching Holocaust films or TV shows or Hollywood movies about World War II. You have an idea about who you are based on what someone else has done to you historically – on some level, the only Jewish identity I had was related to the Holocaust because that was drilled into me.”

Schorr explains that being in love with a German woman and living with her family mixed up those ideas: “my mind bounced around from Jewish Massad heroics to Stockholm syndrome because by the seventh year I was firmly entrenched in that family and in that town. I loved the people and the place.” Yet Schorr remembers seeing family photo albums in her friends’ homes – sometimes the images of family members with Nazi uniforms had been removed, sometimes they were left there. “You’d think, ‘Ah, they don’t keep those photos,’ or if they did, you’d wonder why they did keep them. Both felt transgressive and problematic to me. It was like there was no rehabilitation really – just silence.”

If living with Belmore (who was French) in the East Village had been a European education of sorts, Germany was totally different. “French nostalgia feels neverending but German nostalgia feels like a tourniquet on a bleeding limb – it’s almost like it’s been cut off. I think my work was sort of about undoing that tourniquet and letting the blood flow.” On the one hand, says Schorr, “I felt such entitlement in Germany like I was allowed to do whatever I wanted because historically my people were so hurt – as though I was in the land of apology.” On the other, she says, she wanted to feel the discomfort, to face it. “It almost became obsessive … I have a real memory of reading Primo Levi’s Auschwitz [book] on the way to Stuttgart [while] on the way to a flea market to look for Nazi treasure. It was fucked up!”

Many subjects appear in August half-dressed in nature, in the gym, or in their backyards – Schorr describes these as “stills from a movie I never made”, explaining: “I always had this interest in what it would be like to observe something evolving and take a picture. In my mind it was someplace between documentary – what would it be to be a reportage photographer – or what would it be like to be a photographer on set for a movie. Probably what I wanted was to be a director and then just sneak off and observe what I was directing.”

“The categories in my work that I was really focussed on were the soldier pictures from August Sander’s work. Almost all of the photos are made in the month of August – so mostly made in that August light – but it was also like I was trying to make August Sanders’ whole portrait of Germany in this one little town that seemed stuck in the 1970s. I was also really interested in Anselm Kiefer and Martin Kippenberger, East German artists who have had a slightly different relationship to Germany.”

“There’s a lot of guilt in the work for me because it’s both dismantling and adoring – the guilt of putting more white meat on the heap” – Collier Schorr

As for the images of boys in Nazi uniforms, there was a sense of forcing the subjects to confront their past. “It was totally sadist,” she reflects. This is where the kink aspect comes in; it was documentary work, yes, but also a Luchino Visconti film. “It was referencing the idea of underground homosexuality in Germany, the uniforms with leather. You don’t need all that stuff to be a soldier, it’s bedroom stuff, costume – and of course, there was a part of me that recognised things in those uniforms from Christopher Street [in New York].”

Revisiting the work now, 30 years later, Schorr says there’s a lot of guilt in making these types of pictures. “I just saw Top Gun: Maverick and thought how amazing [it is that] in this period of time, we’re still so up for something about patriarchy and white supremacy. But my work is shaped by that – by watching those movies as a kid – [and] as what’s heroic. The work is about dismantling that, but it’s like I had to dismantle it through the actual body. So there’s a lot of guilt in the work for me because it’s both dismantling and adoring – the guilt of putting more white meat on the heap.”

Would she make the same work again? Probably not, she says. “I’m older and I moved through a lot, but it was very cathartic.” Crucially, not just for her but for her subjects. “I remember kids saying we should have tried on these jackets in high school. They [the subjects] all had different reactions to the costumes, and in some ways, those reactions represent feelings I had; excitement, feeling impressed, shame, feeling worried, scared, humiliated.”

At a time when Russia is invading Ukraine, and people are accusing Ukrainians of being Nazis, this work still feels relevant, muses Schorr. “It’s like, no matter what you do, you throw a stone [and] it hits some kind of Nazi representation – it’s a piece of history that feels forever rippling”

August by Collier Schorr is published by Mack and is out now.