Currently on show at the David Hill Gallery in London, Bissiriou’s photographs were created in the Benin village of Kétou in the late 1960s to late 1980s – but they’re as powerful today as they ever were

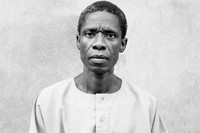

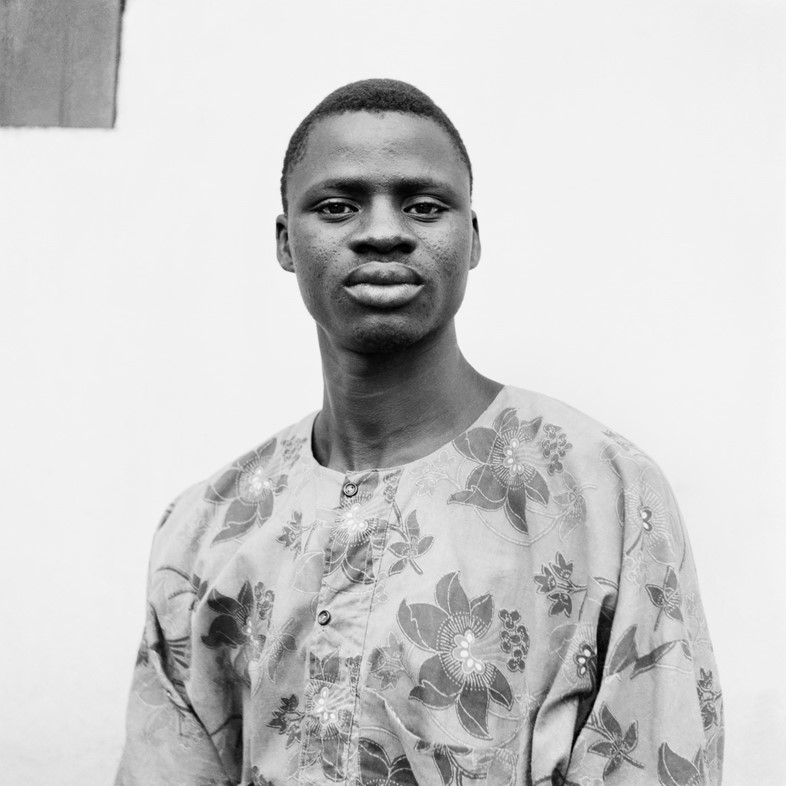

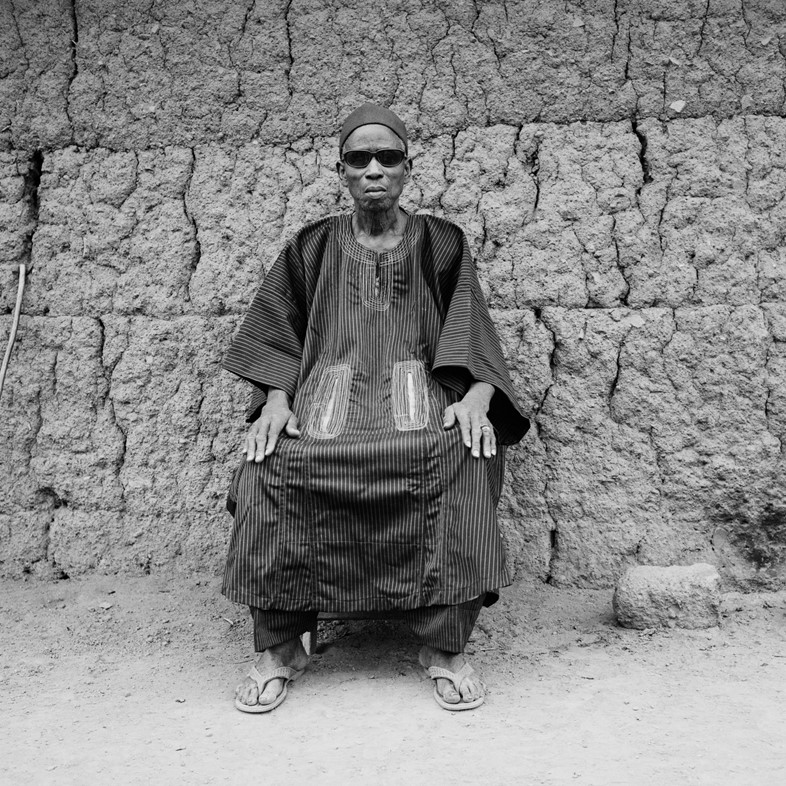

“This selection of work stands out because unlike most of the ID cards taken at the time – which are more formal and somehow rigid – Rachidi Bissiriou’s have a wonderfully contemporary, relaxed feel,” says David Hill, founder and director of the David Hill Gallery in London, which is currently hosting an exhibition of the West African photographer’s work. “His sitters just have that air of ‘cool’, despite posing for the camera,” he continues. “They have a natural and palpable rapport with the photographer.” This natural photography style, which is rare in a period of West African photography where most images are carefully staged and posed, has helped turn Bissiriou’s oeuvre into the culturally and historically significant body of work that it is today.

Born in 1950 in the Benin village of Kétou, Bissiriou came into his own as a photographer eight years after the Benin Republic gained its freedom from its French colonial masters. By 18, Bissiriou opened his Studio Pleasure right in Kétou and became popular for photographing his community members, and the relaxed images he took of them. Studio Pleasure ran for over 36 years until Bissiriou closed up shop and retired from photography, breeding chickens and sheep instead, and served a stint in local politics.

Bissiriou inadvertently documented some of Benin’s most politically significant time periods through his photographs; his work serves as a great reference for people wanting to understand the life, culture and then-forming national identity of the people who would become known as the Beninese. Though this was not what he set out to do. “Mr Bissiriou was a commercial photographer who operated his studio from 1968 to 2004,” says Hill. “He viewed himself as a successful tradesman or craftsman at most. Looking at the images now and putting his work in context, we can see it as an incredible document of townspeople that had recently emerged from 88 years of French colonial rule.”

Perhaps what made Bissiriou’s work garner its cultural importance is the casualness of his subjects, which also points to his ability to connect with them. This is especially impressive as he captured these images when cameras were generally treated with great suspicion by the masses. “All great portrait photographers are highly charismatic,” Hill points out. “They need to be ‘people’s people’ to quickly connect with their subjects and put them at ease, which Mr Bissiriou was clearly a master at.”

In 2019, Hill was presented with negatives of Bissiriou’s work by French record dealer Nuno Filipe da Silva Aires, and instantly recognised their cultural and historical importance, as well as their beauty. “I am an avid record collector, and in addition to the soul, jazz and reggae that I buy, I also collect 60s and 70s West African records,” he says. “A record dealer that I know, who is aware that I have a photography gallery, told me about a studio photographer he’d met in Benin called Rachidi Bissiriou, and asked if I would like to see some negatives. I have seen the work of many West African photographers, but these images feel fresh and entirely different to me. The contemporary nature of his compositions and the direct connection Mr Bissiriou has with the subjects sets this work apart.”

Carrie Scott, co-curator and exhibition partner on Gloire Immortelle, tells me she was similarly moved by seeing Bissiriou’s work. “When David first showed me these portraits, I nearly fell off my chair,” she says. ‘There’s a precision to the work, and a presence in each portrait that feels so fresh. I hardly believed David when he said they were shot more than 40 years ago. I also was very familiar with Irving Penn’s portraits from the same era, in the same part of the world, and couldn’t help but also be seduced by the more accurate representation of Benin that Bissiriou was giving us. His portraits feel like a gift.”

Since 2019, Hill has represented the archive of Rachidi Bissiriou and, in the same year, hosted Bissiriou’s first-ever solo exhibition. Currently, the David Hill Gallery is currently presenting Gloire Immortelle, a solo exhibition by Bissiriou, which runs until 29 July 2022. The show includes previously unseen portraits and coincides with the V&A’s Africa Fashion opening in July, which features three images by Bissiriou.

“We get to see self-representation in these images, not a western look at Africa,” Scott tells AnOther. “Comparing the portraits in our exhibition to Irving Penn’s Photographs of Dahomey (1967) portraits is a pretty eye-opening exercise. Penn’s conditioned objectification and the primitive filter on his lens is plain to see in these images. These two men were shooting at the exact same time. Penn shot the series for Vogue in 1967. Bissiriou set up his studio in 1968. And yet Penn’s feel like they were shot a century earlier. It’s sad that we are only just now seeing Bissiriou’s images – fresh-faced men and women, dressed in the latest fashion – while Penn’s have been in Vogue, celebrated in museums – the title of the main essay in the Dahomey book is Quest for Beauty in Dahomey, which almost reads like Penn had to go out and search for beauty, whereas Bissiriou easily and obviously found it on the streets of Benin, all around him.”

Ultimately, this exhibition provides insight into the work of one of West Africa’s most important image-makers, and a glimpse into the lives of people who navigated and experienced a significant and pivotal moment in Beninese – and African – history.

Rachidi Bissiriou: Gloire Immortelle is at David Hill Gallery until 29 July 2022. An accompanying book is published by Stanley/Barker, and is out now.