Though she wasn’t embraced by the art world at first, Resnick was an influential photographer in New York’s downtown scene through the 1970s and early 80s – a new exhibition proves her recognition is long overdue

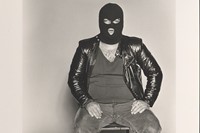

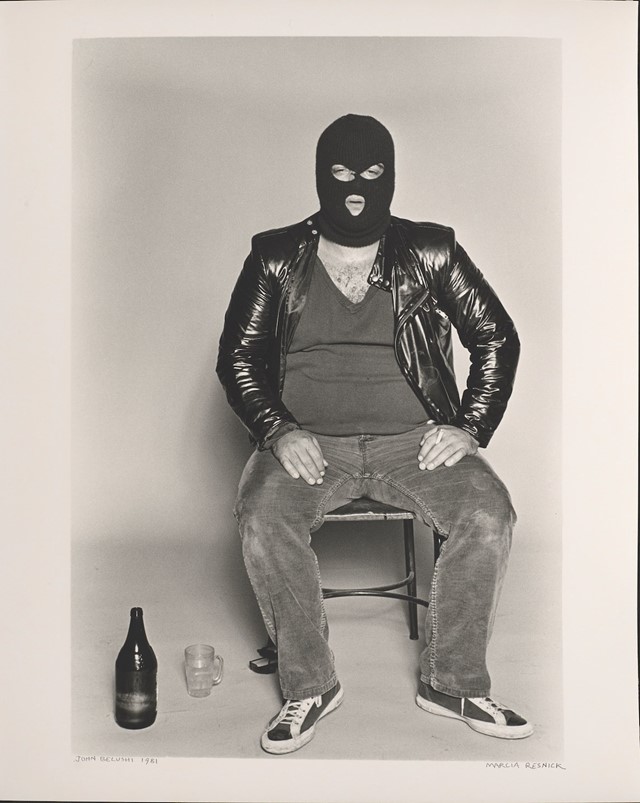

When American photographer Marcia Resnick went to meet Mick Jagger about shooting a potential cover story for High Times in 1979, she turned up plied with cocaine. While leading Joseph Beuys down the spiral ramp of the Guggenheim Museum to photograph him there in the same year, she flashed him “a little leg” to soften his demeanour. And after encountering a “pretty high” John Belushi at Tribeca’s AM/PM nightclub in 1981 – six months before he died – he ended up back at her loft, posing for her in a ski mask at 6 am.

Nothing about Resnick’s approach to photography has ever been orthodox. But for decades, it hasn’t been properly recognised for its originality either. That changed in February of this year when the touring museum retrospective, Marcia Resnick: As It Is or Could Be, opened at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Maine, USA.

Now 71, Resnick was an influential figure in New York’s downtown art scene through the 1970s and early 80s. She got her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts (also known as CalArts), where she used her camera as a vehicle for conceptual art – oil painting on top of her images; toying with scale and framing – long before mainstream conceptions of photography transcended simple documentation. She studied under John Baldessari, alongside David Salle, Jack Goldstein, James Welling, and other members of the ‘Pictures Generation’. But when their famous exhibition premiered at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2009, Resnick was not included.

“I never got lumped in with them [my contemporaries],” says the artist, speaking over Zoom from her eclectic home in Brooklyn. “I should have.” Resnick’s long hair and wide smile dominate the screen as she shuffles continuously around in her seat. “They say it’s a movement disorder,” she remarks. Though only diagnosed recently, the condition informed her portraiture in her heyday: her constant dynamism “evoked responses” in her subjects, cultivating a unique kind of energy in the room.

Resnick graduated from CalArts in 1973, before making the cross-country trip back to her native New York to take up a part-time teaching position at Queens College. She lived with a dancer named Pooh Kaye, paying just $70 per month each for an apartment on Bowery and Houston Street. In 1974, they moved to a fifth-floor loft just off the Hudson River with a swathe of fellow artists (including Laurie Anderson). With fourteen windows soaking the place in sunlight, it was a 2,000-square-foot bohemian dream. “It was freezing,” Resnick says. “I often slept in a sleeping bag in my darkroom … But it was affordable at the time.”

For ten years, Resnick existed at the epicentre of an intoxicating period in cultural history; the era of New York’s downtown art scene. A punk at heart, she spent night after night at CBGB, Max’s Kansas City, and the Mudd Club, finding kinship in a community of fellow libertines; a “close-knit” milieu of painters, filmmakers, musicians and writers. They irrevocably influenced her art, and she theirs: “the scene” was her home and her muse.

But less positive experiences altered the course of Resnick’s output, too. In 1976, she crashed her Chevy station wagon in the West Village. “I went unconscious, and when I woke up, I was lying in the hospital,” she recalls. Just 25 years old at the time, it was a surreal, near-death moment; one that drove her to contemplate the life she had led thus far, and the experiences that made her who she was. “It sort of spurred my creativity,” she says. “I started to write things down.” Scribbles of text and sketches, alongside photographs she was taking during her two-week hospitalisation, would go on to inform her 1978 book, Re-visions.

Where Resnick had previously been pushing the boundaries of photography by drawing on her images, or cutting out fragments, in Re-visions, she started to combine them with text (“Not captions,” she says. “That’s very important.”) Channelling, in part, sentiments of the Women's Liberation Movement and the Sexual Revolution, staged images told the story of a young female character navigating the jarring space between girlhood and womanhood. Resnick was questioning constructs of gender, class and morality, while nurturing a unique verbo-visual language that fused shrewd social commentary with irony and humour.

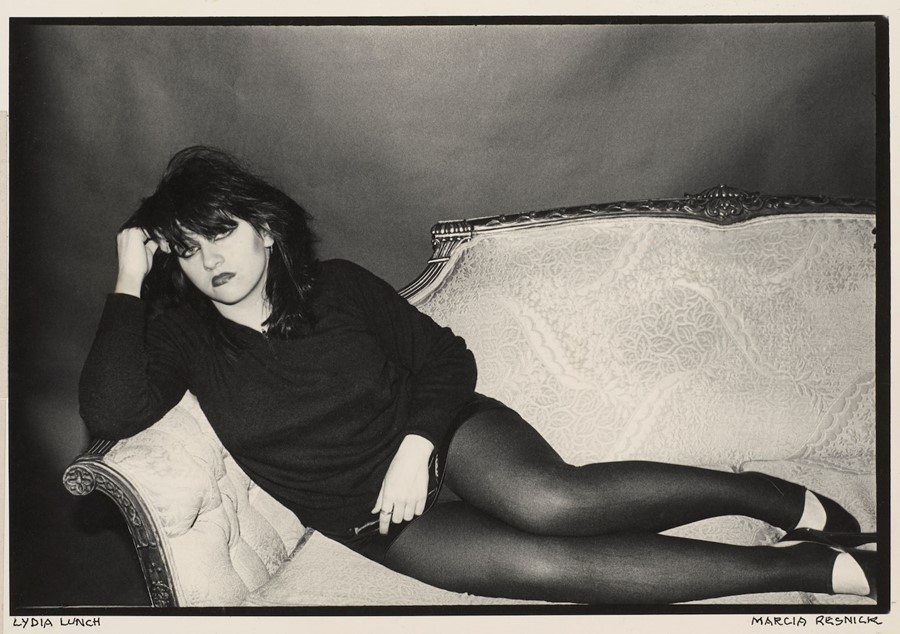

After exploring herself in this way, she moved on to interrogate another subject she didn’t understand: men. A shift away from conceptual art saw Resnick turn to portraiture, often of people she met on nights out – and it was the ‘Bad Boy’ trope that fascinated her. “A Bad Boy doesn’t have to be the prototypical James Dean character. Or like Marlon Brando in The Wild One,” Resnick says in her culminating 2015 book, Punks, Poets and Provocateurs. A Bad Boy is someone who has a special magic, who has charisma, and who braves living on the edge.”

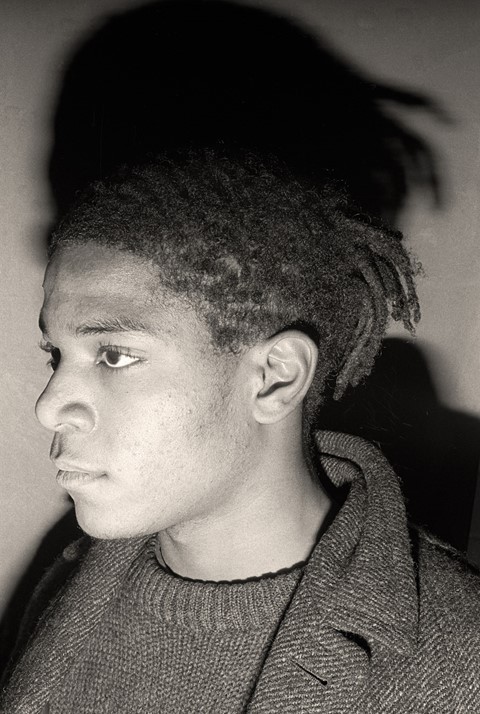

From 1977 to 1982, Resnick captured some of the most enduring counter-cultural icons of modern times: sizzlingly candid shots of Mick Jagger, Allen Ginsberg, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Andy Warhol. But by 1983, the Aids crisis had begun dampening the raw and vibrant sexuality of the era. “It changed people,” Resnick says. “It changed the social worlds. Things became more insular.”

Seemingly overnight, a lot shifted for Resnick. She lost friends to the epidemic. She endured a difficult divorce. Soho Weekly News, who had been commissioning her to cover the downtown scene via a column titled ‘Resnick’s Believe-It-Or-Not’, went under. Her artistry stalled, and she applied herself more single-mindedly to teaching.

But looking back, there is a lot more to the artist’s legacy than her more famous shots of the downtown art scene. A product of sheer innovation and dedication to her craft, Resnick’s decade-long oeuvre spanned experimental, conceptual, documentary, and editorial photography; not to mention four unique photo books at a time when such a medium was largely reserved for men. Though she wasn’t institutionally embraced, nor did she make a cent off her art until the 21st century (“it was always just a labour of love”), she played a part in the evolution of the photographic medium as we know it. And her recognition is overdue.

Marcia Resnick: As It Is or Could Be is on at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Maine until 5 June 2022.