Seiichi Furuya met Christine Gössler, an aspiring actress and Austrian student of art history, in 1978. They married a few months later, and in 1981, had a son. From the beginning, Furuya felt compelled to photograph her. “I have seen in her a woman who passes me by, sometimes a model, sometimes the woman I love, sometimes the woman who belongs to me”, he wrote in Camera Austria in 1980. Together, they built an archive of thousands of images; an archive which Furuya has revisited, time and time again, since Christine jumped out of a ninth-floor window in East Berlin in 1985. These excavations have materialised in a series of photo books collectively entitled Mémoires (1989, 1995, 1997, 2006, 2010, 2020). It’s Furuya’s monument to his great love; his testament to the ties that bind and abide.

The latest addition to the series, First Trip to Bologna 1978 / Last Trip to Venice 1985, comes via Furuya’s second collaboration with Chose Commune, and hits almost every emotional note. In many ways, it reads as a travelogue, divided into two trips that bookend his relationship with Christine. The first, a newly composed series titled First Trip to Bologna 1978, is comprised of stills from Super 8 film recorded one month after they met; the second is a re-edited version of Last Trip to Venice 1985, first self-published by Furuya in 2002. Much happened in between – and afterwards, too. But while this book – and indeed the photographer’s work at large – is invariably hinged to nostalgia, Furuya’s revisions transcend time and place, for he probes how photography can not only grieve a past life, but reimagine a new one.

Here, Furuya discusses his new book, the impetus behind Mémoires and what it means to mourn through photography.

Alessandro Merola: How did you meet Christine Gössler?

Seiichi Furuya: On 17 February 1978, Christine and I met at the opening of Gwenn Thomas’ exhibition Color Photographs at the Forum Stadtpark in Graz, Austria. She showed up with a woman I already knew, and she introduced me to Christine. After the ceremony, the attendees must have had a chat at a pub somewhere in the city, and she must have been there and I must have got her phone number. I don’t remember exactly what happened next. I must have had too much wine.

Ten days later, I found the courage to call Christine and invite her on a date. Our relationship became inseparable from the day we saw the ‘jidaigeki’ film Harakiri (1962). It must have been a few years after her death when I discovered these scribbled words in my diary: ‘I invited her to a movie, but I’m a little late. Christine looks a little angry. The scars on her neck and wrists are bothering.’ Now that I think back, I realise that our relationship began and ended with suicide.

Christine visited my apartment the following day, and it was here that I took the first picture of her. From that day on, we met almost every day, and, although my diary states that we travelled to Bologna from 18–25 March, strangely enough, I still can’t recall anything about our trip. I took my Leica and my Super 8 camera which I shot films with. The fact that Christine’s colleague gave us a lift to Bologna was only revealed when I watched the digitised films which I discovered in my attic in 2018. However, instead of bringing back memories of the trip, I couldn’t recall anything for over a week. This didn’t change even after looking at the many photographs and videos I took during our stay.

According to Christine’s diary, I made up my mind to marry her while we were in Bologna. One week after returning, we went back to Japan and took part in a Shinto-style wedding ceremony at my home in Izu. With that, our relationship quickly moved to the next level. Thinking back, it may have been the happiest time for us, although she seemed a bit caught off guard by the sudden change in her environment. Within three and a half months, we were married.

AM: Do you have any memory of shooting the films?

SF: Very little, however, a detailed list I produced after digitising all the films showed that from the time I met Christine until the end of my trip to Bologna, I filmed three films totaling just over 20 minutes. Yet I have no memory of the two of us watching them together. In those days, it took a lot of time and effort to prepare a projector and screen to view Super 8 film. I was never a video fan, and I think I was so busy with my daily life that I rarely watched or edited the films I made.

AM: What was your process for selecting the stills from the footage?

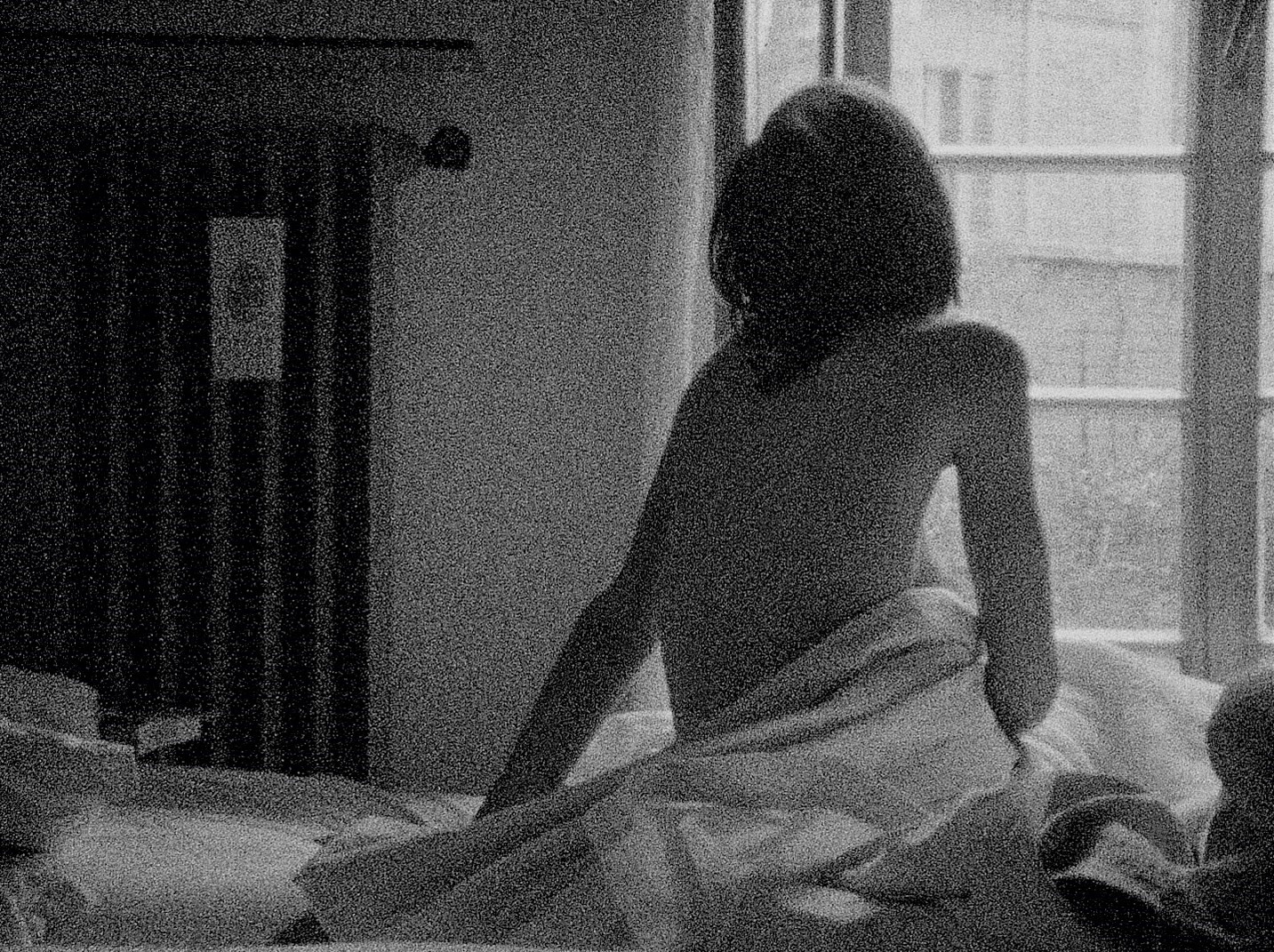

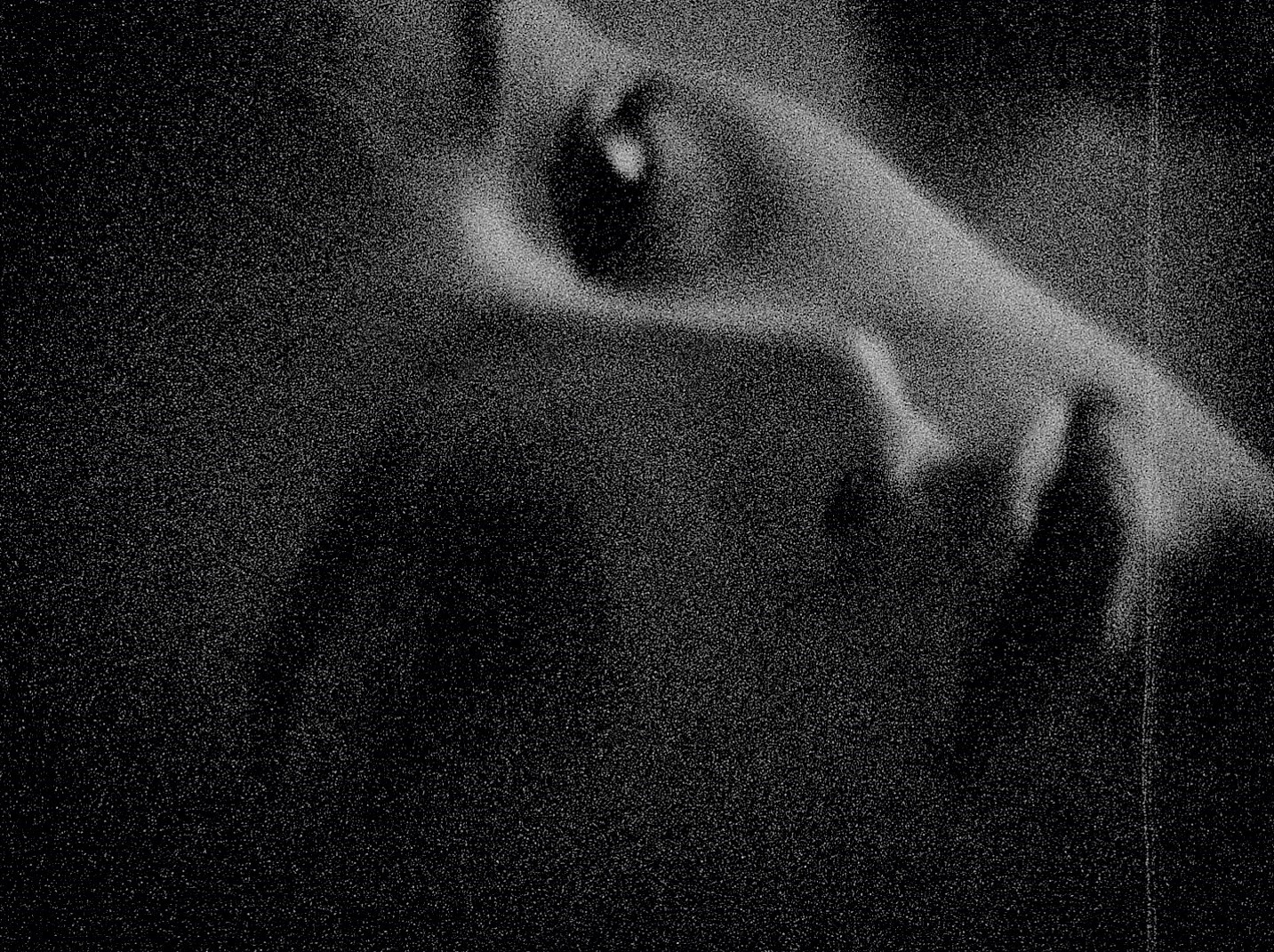

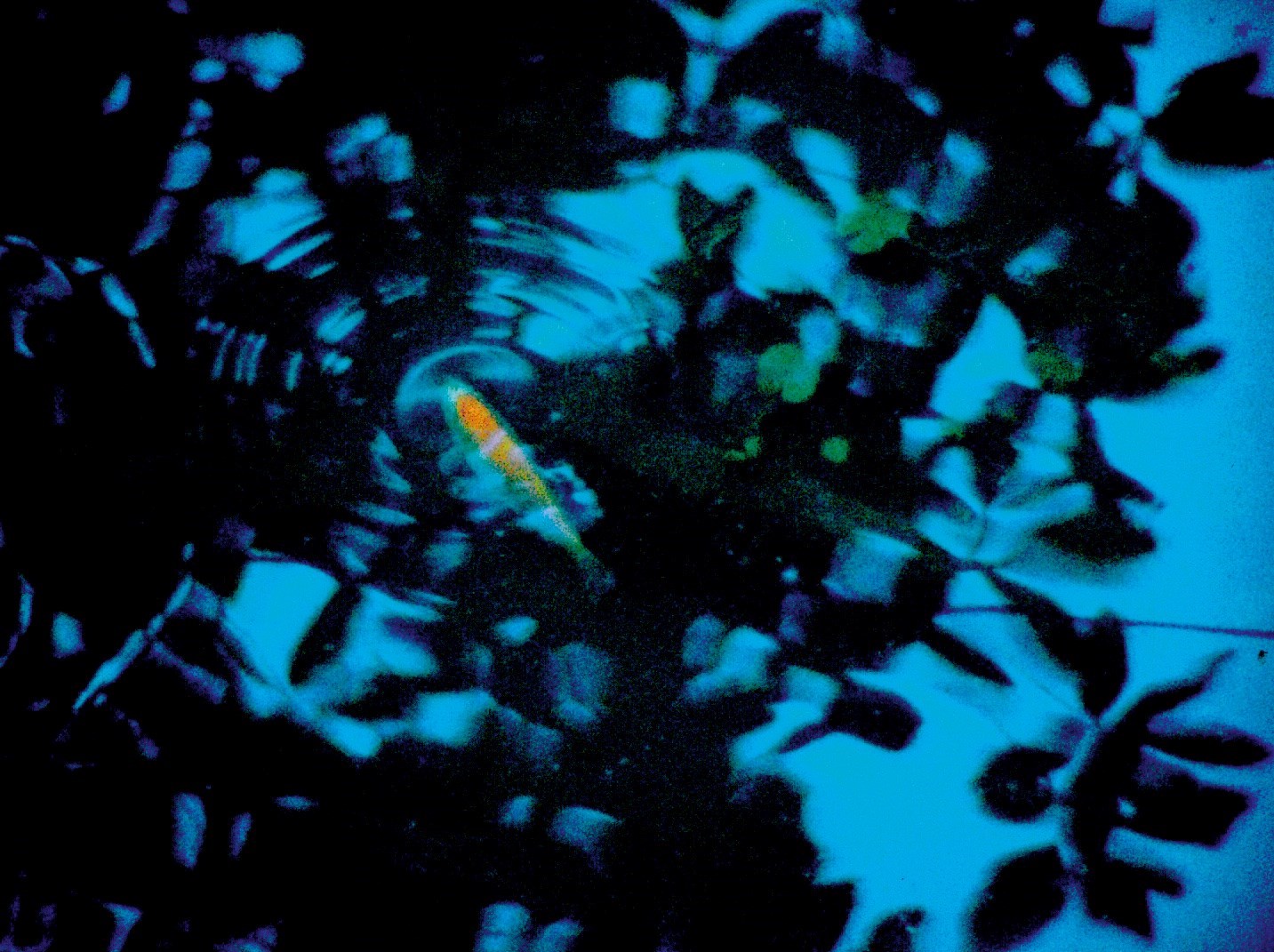

SF: I watched the three films several times in a row. As I followed the dark, grainy images, I almost felt as if I was watching scenes from a famous movie. One after the other, scenes that seemed to have never existed in my memory – and, therefore, could not have been lost from my memory – appeared before my eyes. At the same time, I felt as if I were right in this moment. Especially when I came across the scene in which Christine, wearing a blue sweater, smiles at me through the mesh of her cocktail hat which she found at the flea market. A nostalgic feeling came over me as I remembered why I fell in love with her. And then, I couldn’t hide my surprise that I was in love with her again, as she acted so vividly in the video. I have shown Christine’s photographs in many photo books and exhibitions, but, of course, they were all still images. When I saw her in motion, I felt a surge of emotion that I could not describe.

It was hard to believe that all this had really happened 44 years ago. But since I had no memories at all, I wondered whether I could, by extracting stills, frame by frame, devise a new memory in the form of a book. I printed contact sheets containing hundreds of frames, laid them out on the floor and waited for a new narrative to emerge. Thus began the editing of what I imagined to be a ‘monogatari’ travel story. For a moment, I had the illusion that our journey to Bologna would begin right now: the tale of a journey that has an air of scandal and mystery about it, the delicate scent of spring floating in the air.

AM: This liveliness seems to be aided by the cinematic sequencing you have deployed here.

SF: I believe the sequencing of the frames excels in depicting the subtle flow of time that is impossible to express when using individual still images. In other words, it gives life to dead images.

AM: And where the first section possesses an air of spring, the second section has a very different resonance. How did the trip to Venice in 1985 happen?

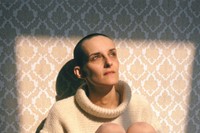

SF: Our family moved from Dresden in East Germany to Graz so that Christine, who had become ill, could seek treatment. She underwent her third hospitalisation and was discharged a week later. The next night, she suddenly said that she wanted to go away and be alone with me. We set off to Venice, and I recorded this four-day trip on two slide films, of which one was accidentally exposed twice. The photographs began with the days surrounding Christine’s hospitalisation and ended with a portrait of her looking back at me with a smile on the ferry. Having moved from Dresden to Berlin for a new job, I mistakenly loaded this already-exposed film back into the camera and shot the streets of East Berlin.

This was our final trip together. Even after Christine left the hospital, her health was not good. Four days after returning from Venice, she had to be hospitalised again. She moved back to live in East Berlin, and her mental state continued to be unstable. Then, on October 7, she took her own life.

AM: In 2002, you self-published Last Trip to Venice 1985. While it shares much of the content of this second section, the sequencing is new.

SF: Our Venice journey remains vividly in my memory, from the moment we left on the express train to the moment we got back home. I knew that this was a limitation, because it was, in many ways, impossible to edit it in such a way that it would feel like a free story. When I contacted Chose Commune about the possibility of publishing a book about Bologna, the editor, Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi, suggested that I should include the Venice trip too. I was surprised and delighted, and we agreed that she would edit the book independently.

“Now that I think back, I realise that our relationship began and ended with suicide“

AM: Christine’s smile – in Bologna, through the mesh of her cocktail hat, and in Venice, from the back of the ferry – reverberates across the book, across the distance of time. Yet much happened in between these two trips.

SF: The ‘blue smile’ of Christine in Bologna – which was probably trying to tell me what was in her heart – could return momentarily, even amidst the days when she was overwhelmed by her mental illness. I had documented those few moments in Venice, jumping seven years in time to encounter the same smile. Of course, it was only after I first saw the dummy of this book that I realised this smile’s ‘jumping’. I still remember thinking: ‘I’m glad we came to Venice,’ as I photographed the moment she smiled slightly at me with her shaved head while crossing the canal on the ferry. Photographing, itself, has always been an act of mourning these beautiful, painful and unrepeatable moments.

Coincidentally, the destinations of the two trips were cities in Italy. And in compiling our first and last journeys in one book, I had an epiphany … People have no choice but to carry their destiny, to fight against tragic evil to fulfil their lives. And we can’t avoid the fact that sometimes tragic evil wins the battle. I chose to present this sad fact in the form of a photo book. I thought, I can’t bury her regret. I can’t kill her twice.

AM: Is this the impetus underpinning the Mémoires books? What Roland Barthes articulated as photography’s ability to mechanically reproduce – to infinity – what happened once?

SF: My first book in the Mémoires series was created as a requiem for Christine. It triggered a revelation … I had to unravel the circumstances that led to the unfortunate ending. The repeated publication of Mémoires was never planned. It was the new uncertainty presented by the book – which I thought would be my last – that compelled me to produce the next. As one thing was clarified, new questions arose. It was a repetitive process. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that I could not find the answer I should have been looking for. If photography had not existed, my life would have taken a completely different path. I would not have been troubled by the intricate yet real past that only comes back through photographs. The ability to forget is very important for human life. However, photographs resist this function. A photograph is a demon that transforms a past moment into the eternal present.

I think that making a photo book is like assembling chaotic and complex images towards one big theme in one’s head. As the work progresses, the outline of the theme becomes clearer and clearer. I think it might be similar to how a composer writes a symphony by combining individual notes. For me, a photo book is like a resume, a record of my life and the transformation of my mental states. I believe the power of photography as a medium lies in the fact that it may enable the expression of something that cannot be expressed in the realm of language. Life is to be lived full of this something.

AM: Is this a belief that has intensified as you have grown older?

SF: Now that I am 72 years old, my creative activities are constantly guided by my remaining time. That is, I am always thinking about what I should do during the time I have left. The first thing on my to-do list is to use the photographs that Christine took during our seven years or so together. It is my attempt to capture her worldview as she would have seen and felt it. The first dummy book has just been completed. It is tentatively titled By Christine 1978–1985, and is about 650 pages long. These photo books are something that I keep making so that I will be able to give Christine a souvenir when I meet her again. They could also be said to be a report of how I lived my life after her death. I, too, will leave this world in the near future … I will literally take the final journey to reunite with her. When Christine was buried in 1985, my son Komyo laid a large portrait of her, an airplane that he had built himself and a bunch of wildflowers that we had picked together from our garden on her coffin. When the time comes, I will take all of my photo books.

First Trip to Bologna 1978 / Last Trip to Venice 1985 by Seiichi Furuya is published by Chose Commune.