As Pirelli turns 150 years old, Emily Dinsdale looks back at the calendar's defining moments; from the golden age of the supermodel to Tim Walker’s all-Black Alice in Wonderland edition

Since its first appearance in 1964, the Pirelli Calendar has become synonymous with a particularly potent species of unambiguous glamour, fantasy, sex, and luxury. Over the decades, its exclusive, glossy pages have yielded an abundance of renowned models and icons, shot by the industry’s most eminent photographers in the most desirable locations on the planet.

Created by the Italian-based tyre manufacturer as a way of elevating their image – a more tasteful alternative to the pornographic pin-ups characteristically found in the machismo offices and garages of tyre dealerships – the calendar was intended to set Pirelli apart from their competitors. What began as an exclusive corporate freebie for the company’s most valued stockists and clients, has, over the decades, become almost an institution in its own right, engulfing the brand to such a degree it’s sometimes easy to forget Pirelli produces tyres.

But this is not just a story of a brilliantly executed marketing idea. The trajectory of the Pirelli Calendar cuts a swathe through the mores of its time, casting a gaze (albeit a typically male gaze throughout the early decades of its development) across the changing tides of fashion in the 20th and early 21st century, not predicting trends but articulating fluctuations in taste and beauty ideals with unequivocal assiduity.

As Pirelli marks its 150-year anniversary, we look back at some of the defining moments in the calendar’s history and revisit some of the enduring and memorable images from across the 48 editions to date.

1964–1974

Right from the start, the Pirelli Calendar was concerned with tapping into the current moment in popular culture. In 1964, at the dawn of ‘Swinging London’ in the UK and the ‘British Invasion’ in the US, Robert Freeman, the British photographer lauded for producing many of The Beatles’ most memorable album artwork, was commissioned to shoot the first published Pirelli Calendar. This inaugural edition established much of what would remain, for many years, the defining aspects of the calendar’s image – codfying its iconography of aspirational wealth and heteronormative sexuality as expressed through luxurious depictions of sun, skin, and sensuality.

But it was Harri Peccinotti’s 1968 and 1969 editions that stand out as the most alluring from the calendar’s first decade. The London-born photographer would make his name as the art director of Nova – the cutting-edge women’s magazine now considered a pinnacle of mid-century graphic design and renowned for its stylish and provocative imagery, including work by the likes of Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, Terence Donovan, Don McCullin, and Diane Arbus. His boldly graphic, erotic photography came to define the calendar’s early years.

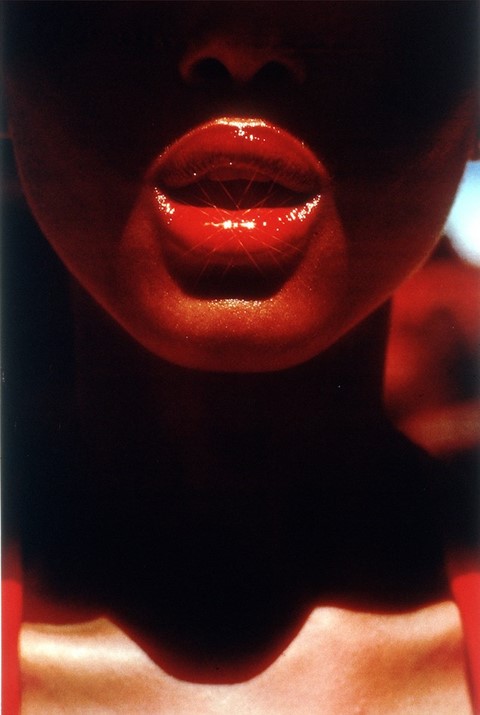

Shot on location in Tunisia and Big Sur, California, Peccinotti’s sun-drenched, colour-saturated photographs are less self-consciously posed than conventional glamour shoots. Apparently inspired by the poetry of Elizabeth Barret Browning, Allen Ginsberg, and Pierre de Ronsard, the Pirelli Calendar in Peccinotti’s hands became more like an erotic fashion editorial. The images oscillate between erotic close-ups – parted lips poised to suck a popsicle or take a drag on a cigarette, bikini-bottomed buttocks, taut skin glistening with moisture – or shot from afar using a telephoto lens with voyeuristic effect.

In 1972, Sarah Moon became the first woman to shoot for the calendar. Having begun her career as a fashion model, she came to prominence in the 1970s as a fashion photographer creating images with a distinctly haunting, elegant quality. At first glance, the photographs she took for Pirelli look like impressionist paintings. Shot in the lavish setting of Villa Les Tilleuls in Paris, her portraits are ethereal and painterly, more Renoir than soft porn.

1980s

Pirelli stopped producing the calendar in 1974. As production costs escalated and the world descended into a period of recession, perhaps the no-expense-spared luxury of the calendar seemed redundant. During its absence – or perhaps because of it – old editions became even more collectable. In 1980, Tate acquired a copy of the 1973 Pirelli Calendar for their collection, bestowing it with a newfound legitimacy.

The calendar reappeared in 1984 – an era of Reagan and Thatcher, of political conservatism, and the rise of the yuppie. Home video had made pornography ubiquitous and the re-launched Pirelli Calendar wholeheartedly embodied these cultural shifts, taking on the mantle of classy porn for execs. Its inaugural 1980s iteration replaced the suggestion of sex with more explicit and, at times, troubling depictions of sexual objectification. It launched with an edition by photographer Uwe Ommer, whose deeply problematic images depict anonymous female naked bodies lying prone on the sand with the tread pattern of Pirelli’s latest tyres across their buttocks.

Yet there were many exceptions, when contributors attempted to enlarge the narrow ideal of beauty that had been so rigidly adhered to in previous editions. In 1987, Terence Donovan shot the first Pirelli Calendar to feature a cast of entirely Black models (including 16-year-old Naomi Campbell), and in 1988, Barry Lategan included a male model for the first time.

1990s

As the 1990s dawned, the sun rose on the golden age of supermodels. The so-called ‘Big Six’ were an elite group of era-defining supermodels who dominated the decade: Linda Evangelista, Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington, and Kate Moss. In 1990, Evangelista famously claimed, “We have this saying, Christy [Turlington] and I … we don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day.” Impressively, five of the Big Six featured in the calendar.

Alongside the most sought after fashion models, the calendar also continued to attract the most vaunted photographers. Herb Ritts, Peter Lindbergh, Bruce Weber, and Richard Avedon all shot for Pirelli during the 1990s, beginning to widening the scope of their subjects to include other, more eclectic types of celebrities. Lindbergh’s calendar in 1996 featured German actress Nastassja Kinski, while Bruce Weber’s 1998 calendar included several male stars such as Robert Mitchum, John Malkovich, and BB King.

21st century

Throughout the 2000s and beyond, the calendar continued to feature the work of acclaimed photographers and an increasingly diverse range of high-profile stars. In 2006, Mert and Marcus shot Jennifer Lopez, Kate Moss and Gisele Bündchen in homage to 1960s Côte d’Azur chic. The 2007 calendar featured a constellation of Hollywood stars including Sophia Loren, Penélope Cruz, Hilary Swank, Naomi Watts, and emerging actress Lou Doillon.

As time passed and the calendar became increasingly conceptual, the shoots embraced more experimental themes such as Karl Lagerfeld’s 2011 calendar on the theme of mythology, where the fashion luminary recreated ancient myths and legends in his Paris studio.

Annie Leibovitz made the most radical departure from convention in 2016 with portraits celebrating influential women chosen for their accomplishments rather than their beauty. Admittedly, it may not sound very radical an idea for 2016, but given the context it was groundbreaking, deviating so dramatically from the perspective of the male gaze. In a series of frank black-and-white portraits, the calendar includes Serena Williams, Amy Schumer, Patti Smith, Yoko Ono, and Fran Lebowitz. Schumer responded on Twitter: “Beautiful, gross, strong, thin, fat, pretty, ugly, sexy, disgusting, flawless, woman. Thank you Annie Leibovitz”, while The Guardian reported Lebowitz’s hopeful speculation: “Perhaps clothed women are going to have a moment.”

In 2018, the Pirelli Calendar reached its visual and conceptual pinnacle. Tim Walker took the calendar to fantastical new heights, re-envisioning Alice in Wonderland with an all-Black cast, designed by Shona Heath and styled by Edward Enninful. Walker’s wonderland featured RuPaul as The Queen of Hearts, Whoopi Goldberg as The Royal Duchess, Lupita Nyong’o in the role of The Doormouse, British-Ghanian model and feminist activist Adwoa Aboah as Tweedledee, Lil Yachty playing The Queen’s Guard, South-Sudanese model Duckie Thot as Alice, and Naomi Campbell returning to the calendar once again, this time in the role of The Royal Beheader. “This calendar is gonna be a historic calendar,” Campbell told AnOther back in 2017. “It’s gonna go down in the history of Pirelli. It couldn’t be more balanced and diverse, which is something we all strive for each day.”

Thando Hopa, who played The Princess of Hearts in Walker’s reimagining of Lewis Carroll’s magical, surreal tale, described this iteration of the calendar as “an important step in counter-development”, moving away from generic, stereotypical imagery that has historically prevailed across all realms of visual culture.

As a space created for the indulgence of epicurean fantasy, the fantasies played out in the glossy pages of the Pirelli Calendar continue to change and evolve, no longer imagined for the sole pleasure of a male spectator. “Any girl, whether she is Black, or Chinese, or Indian, they should be able to have their own fairytale,” Hopa told AnOther in 2017, reasserting the imperative of championing an all-encompassing vision in the creation of “images that are inclusive in every way and expand our imagination by not restricting people to certains kinds of narratives in those images. Alice can be anybody, that’s the whole point of it.”