As a new biography of American painter Florine Stettheimer is released, Abigail Ronner provides a brief introduction to her life and work

In 1946, Marcel Duchamp curated the Museum of Modern Art’s first ever retrospective of a female artist – his recently deceased close friend, Florine Stettheimer. An early 20th-century modernist artist and feminist, Stettheimer was notoriously private, and her work wasn’t shown widely again until a Whitney retrospective in 1995. She has remained an artist’s artist, with an elusive legacy that Barbara Bloemink has uncovered in her new biography: Florine Stettheimer, released last week.

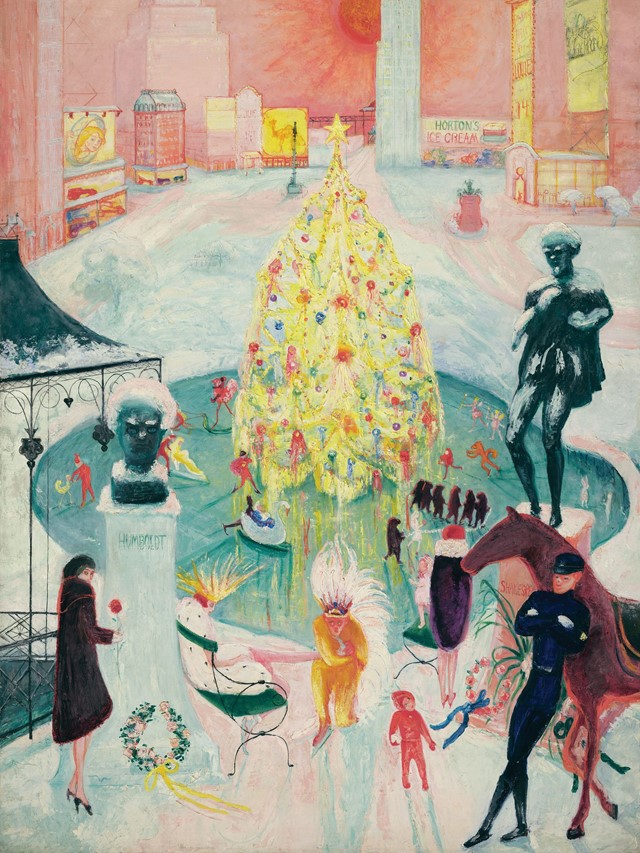

Through Bloemink, we come to know Stettheimer as a wry, witty and easily offended Jewish socialite who kept her work and self-image under tight control. Born in Rochester in 1871, she spent much of her life travelling between the US and Europe, before ultimately settling with her mother and two sisters in an apartment on West 76th Street in New York City, where they were known for their salons. Stettheimer had a long list of famous artist friends; in addition to Duchamp, she ran with Georgia O’Keefe, Alfred Steiglitz, and Gertrude Stein, among others.

Many in the art world consider her a visionary feminist artist ahead of her time, but her own reticence, along with some unlucky twists of fate, concealed her legacy from the general public for much of the last century. As Bloemink’s biography is released, we provide a guide to the life and work of Florine Stettheimer, with input from the author herself.

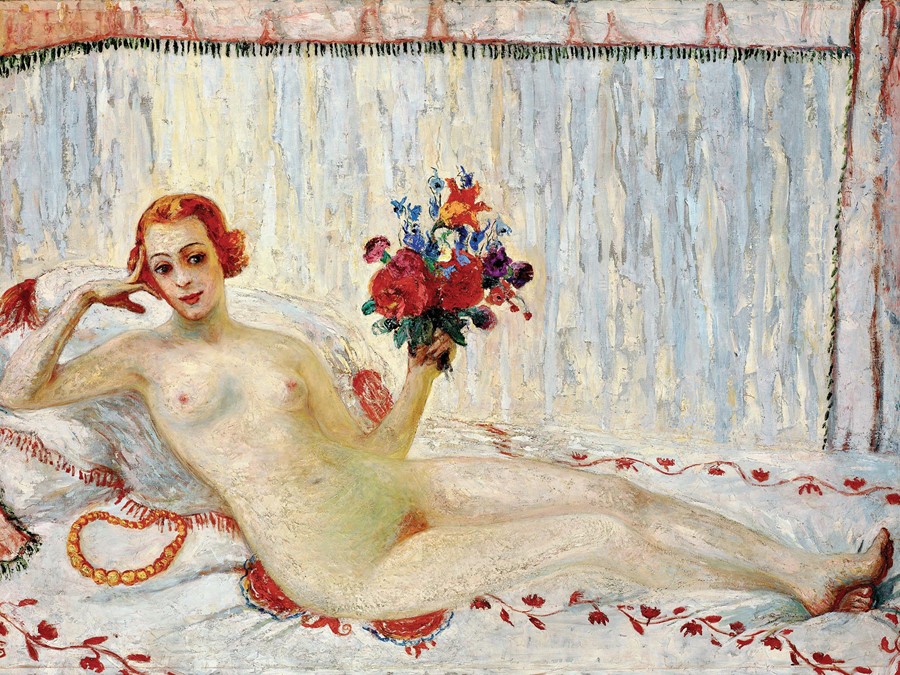

1. She’s known for painting the first female nude from the “female gaze”

50 years before John Berger coined the term “the male gaze” in his seminal work Ways of Seeing, Stettheimer painted the first nude self-portrait ever to be painted from the perspective of the female gaze. Like many women throughout history, Stettheimer was likely cognisant of the male gaze (though, perhaps subconsciously so) and chose her pose as a feminist play on Manet’s painting of the prostitute, Olympia, a famously provocative painting that called out the inherent sexism of the reclining nude, wherein a woman is portrayed naked and lounging, ready to receive the gaze of men. Stettheimer was 45 when she painted it, which would have been considered outrageous at a time when women’s dresses still hovered around the ankles. The painting wasn’t exhibited publicly during Stettheimer’s lifetime and wasn’t even labelled a self-portrait until the mid-90s.

2. She took on feminism and sexuality at a time when “feminine” was synonymous with “bad”

Stettheimer courted controversy by using a “feminine” style in her paintings, particularly her self-portrait where she utilised the “s” curves of the rococo. This tendency aligned her with European modernism at a time when American critics were warning “against the dangers of the ‘feminine in painting.’” Stettheimer’s paintings upended gender binaries and challenged traditional sexuality. “She often painted herself in white pantaloons she had especially made,” Bloemink tells AnOther, “a symbol at the time of women’s suffrage and the ‘New Woman’ as well as holding her paintbrush and palette showing herself as a professional artist.” In her painting Lake Placid, she reverses the gender roles of her subjects, painting men as the objects of pleasure for the female gaze. In Spring Sale at Bendel’s, which she painted less than a year after women gained the right to vote, she creates a distinct “women’s space,” unlike the usual male-dominated or co-ed spaces of the time.

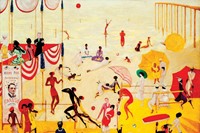

3. She used her paintings to highlight racism

Stettheimer also chose to paint sites of social unrest, seeking to underscore the struggles of the times. In Asbury Park South, Stettheimer’s focus is a predominately Black beach community in New Jersey that began to face segregation at the hands of whites two decades after the civil war ended. And as a member of a prominent Jewish family, she also chose to paint Lake Placid where, at the turn of the 20th century, anti-Semitism thrived. Bloemink is careful to state that Stettheimer was not an activist, but she was deeply engaged with progressive politics in her own creative ways.

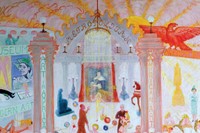

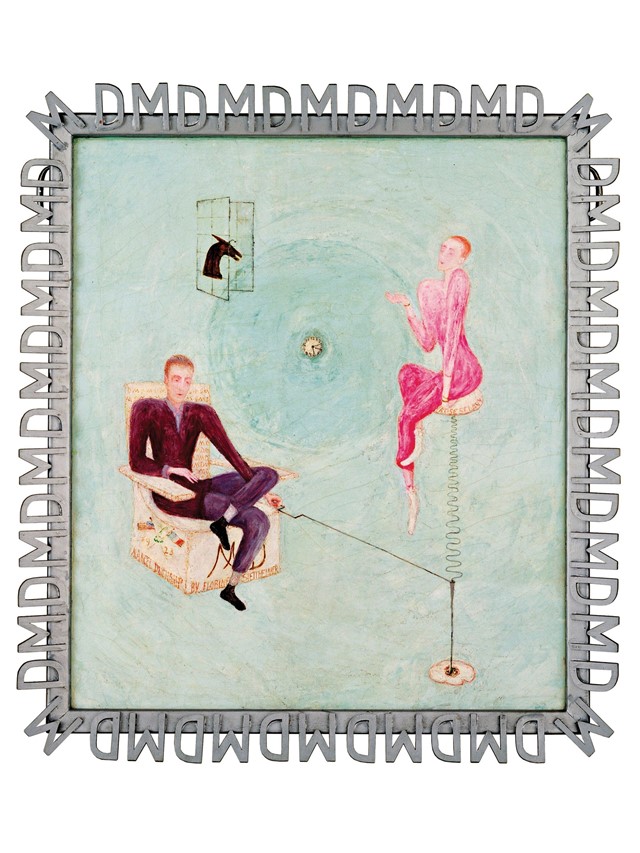

4. She embraced surrealism and became best friends with Marcel Duchamp

As her style matured, Stettheimer left behind the classical traditions of European painting in favor of surrealism. She joined her friend Georgia O’Keeffe in denouncing the feminine, wearing shapeless, severe clothing, and portraying herself eight years after the initial nude self-portrait as a sexless, floating figure in the painting, Portrait of Myself. She had an especially close relationship with Marcel Duchamp, who was one of few people she allowed to draw her portrait (though she painted five of him), and who tried to publish one of her poems in a Dada magazine. Stettheimer, being deeply private, declined. Bloemink even suggests that Duchamp’s alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, was modelled after Stettheimer in Man Ray’s famous photograph, Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy.

5. Yet, her legacy is still under-recognised

“For decades, Steiglitz begged Stettheimer to join his gallery and become one of ‘his’ artists, as did most of the other major gallerists at the time,” Bloemink tells AnOther, but Stettheimer preferred painting portraits for her close-knit circle of friends and quietly documenting the creative and social scenes particular to the New York of her time. However, it wasn’t simply privacy that kept her work out of the mainstream – in fact, she exhibited often during her lifetime – rather, she held grudges and snubbed those who she felt snubbed by. This included Alfred Steiglitz, who reportedly didn’t appreciate her portrait of him, and who had to write her an effusive note of praise before she gave it to him – one of only three works she gave away during her entire lifetime. The truth is that despite her introverted ways, Stettheimer was an artist ahead of her time. Her work was prescient and challenged the status quo.

Florine Stettheimer: A Biography by Barbara J. Bloemink is out now.