Visual inundation may seem like a contemporary phenomenon, but a new exhibition at New York’s International Center of Photography argues that it’s been going on for at least a century

Image proliferation feels like a distinctly modern phenomenon. There is seemingly endless commentary around the ‘flood’, ‘bombardment’ and ‘inundation’ of images we are fed on a daily basis; an issue often attributed to the internet age. It’s true that our fascination with, and unease about, the amount of images in the world has been amplified by the rise of camera phones and social media. But its history goes back a lot further. This history is the subject of the International Center of Photography’s latest exhibition, A Trillion Sunsets: A Century of Image Overload, curated by David Campany.

“Hardly a day goes by when somebody doesn't say to me there are too many images in the world,” muses Campany over Zoom, perched in the centre of one of ICP’s bright white gallery spaces. “It’s an odd one, because on the one hand, I get it. But on the other hand, I think, well how many would you like? What was an appropriate number? And if we have exceeded it, what are the consequences of that?”

“It’s a slightly facetious response,” he adds, wryly. “But it does get us to an interesting problem. And it’s a problem we always think is new … But then you look back, and it’s been here for 100 years.”

The term “mass media” was coined in the 1920s, denoting the advent of mass-circulation newspapers and magazines in the wake of the First World War. The boom in illustrated press brought with it more and more emphasis on images, to which cultural commentators and critically-minded artists soon began to respond. “People started to ask questions that feel incredibly contemporary,” Campany says, “like, is the number of images going to disturb civil society? Can our psychology take it? Is ‘truth’ being lost?”

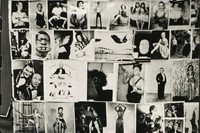

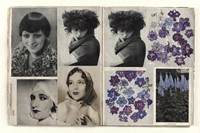

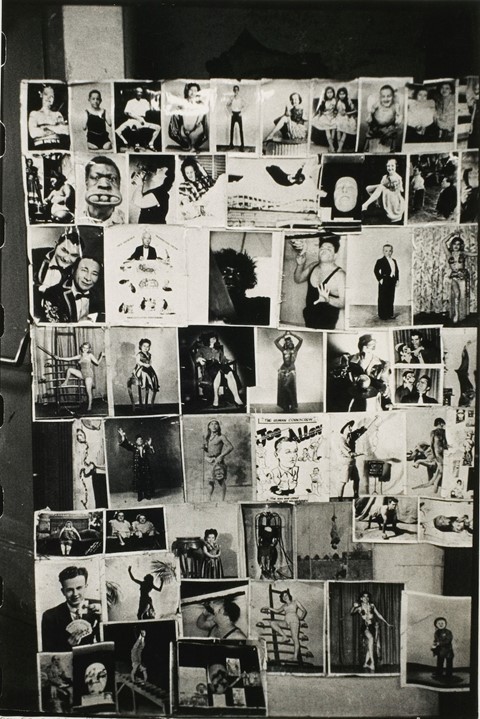

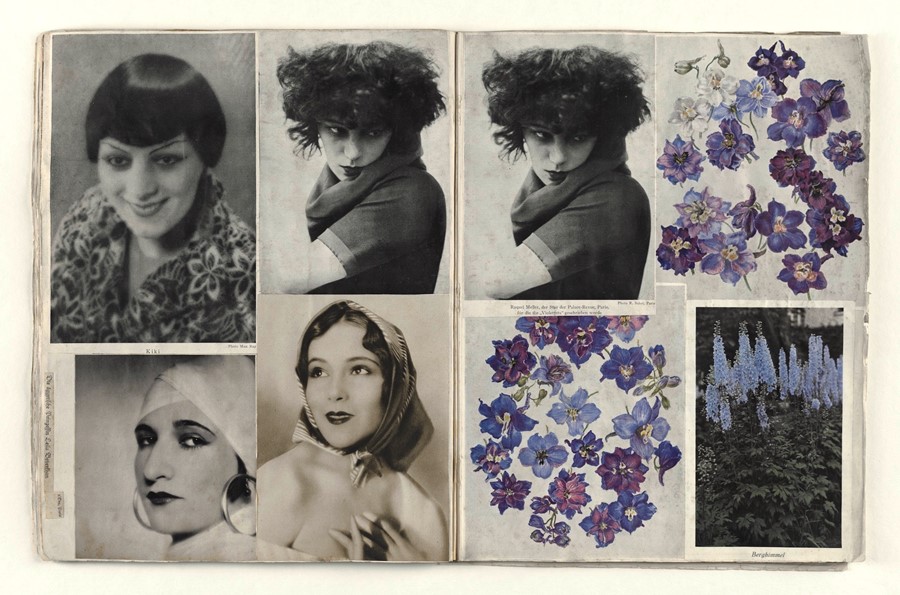

A Trillion Sunsets opens with German artist Hannah Höch’s Album, completed in 1934. Hoch – who helped pioneer the mediums of collage and photomontage in the 20s and 30s – shrewdly reappropriated and recombined images and text from the mainstream media to critique popular culture, the spectre of German fascism, and constructions of gender. Album is a scrapbook into which Höch pasted hundreds of photographs cut from magazines and newspapers, spanning fashion photography and film star portraits to animals and architectural shots.

“It’s difficult to know exactly what she was thinking about those images,” remarks Campany, “but it’s as though she’s noticing, already, the visual habits that were emerging. Where do conventions for women's beauty [come from]? How are non-Europeans represented in European media? Why are commodities lit a certain way in advertising? Why do tourist images look the way they do?” In a visual era defined by Instagram grids and Pinterest mood boards, Hӧch’s dissection of formulaic images feels strikingly modern.

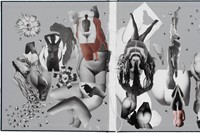

From here, Campany divulges, the exhibition “lets loose”, taking viewers on a non-chronological journey through the decades: exploring how the art movements of Dada, Surrealism, Pop, Situationism, Conceptualism and Postmodernism were all, in different ways, horrified and mesmerised by society’s ever-unfurling image supply.

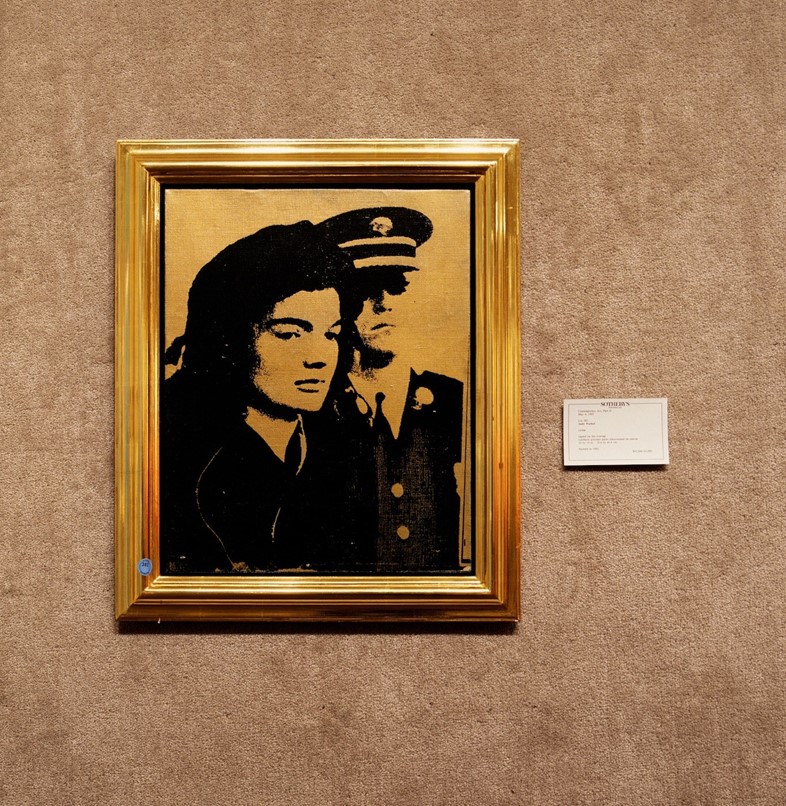

A defining factor of Campany’s curation is the parallels he draws between artists from different time periods. Nakeya Brown’s If Nostalgia Were Colored Brown (2015) is a series of pastel-hued still lifes picturing album covers of Black women artists amidst hair products and paraphernalia; the project probes the pressures of Eurocentric beauty standards, and the subversive political implications of Black women ‘going natural’ with their hair. Next to Brown’s work hangs an advertising image of a white woman’s eye reflected in a cosmetic compact mirror – in this context, the watchful, even disapproving eye of the status quo – appropriated by Richard Prince in 1983.

Contemporary artist Emma Sheffer – who runs the Instagram account @insta_repeat – collates ‘amateur’ image types to probe their homogeneity: the same natural landscape or scene, captured by numerous different people, and yet all ascribing to the exact same composition. “She’s actually doing exactly what Hannah Höch was doing in the 20s and 30s,” Campany points out. “Highlighting these visual patterns that are emerging, and questioning why.” As the title of the exhibition would suggest, A Trillion Sunsets goes some way in interrogating the role of the amateur photographer, and the bind within which they are caught — that is, somehow meaningfully trying to explore their own life, and conforming to the image standards that already exist.

A Trillion Sunsets is not an exhibition that answers questions. But it asks a lot of them. “Have your way with images, or they’ll have their way with you,” wrote Campany in his 2013 book, Gasoline. It’s a phrase he’s kept coming back to in the years since. Ultimately, we can complain all we like about the amount of images in the world — but that number isn't about to shrink. All we can really do as scrollers, consumers, observers, people, is continue to question the imagery that shapes our culture. At the same time, we can look to art to help us challenge it: as a space for processing, playing, critiquing and reclaiming; for finding catharsis, and having our own “way”.

A Trillion Sunsets: Century of Image Overload is on at the International Center of Photography Museum in New York until 2 May 2022.

![Robert Capa, [Artist making collages, Paris], 1934–35](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/200/0-1562-2154-1436/azure/another-prod/410/7/417149.jpg)