Born out of research on critical whiteness theory, Daniel C. Blight’s new book, The Image of Whiteness, is a curation of art, photography and academic discourse

In Daniel C. Blight’s new book, The Image of Whiteness, we are confronted with the “troubling story” of racial and political whiteness. Blending art, photography and academic discourse, the project explores the falsehoods and paradoxes of whiteness, as well as its oppressive nature. It also highlights the crucial work contemporary photographic artists are doing to “subvert and critique its image and its continuing power”.

In the book, Blight examines whiteness not only as a political or social phenomenon, but also as a visual construct. ”From early colonial photography in the 19th century to contemporary social media and photographic art, photography has always played an integral role in the maintenance of the political and social hegemony of whiteness,” explains the London-based academic. “The technology of the camera is not innocent, nor are the images it produces or the people who make them.”

The Image of Whiteness was born out of a conference that Blight organised in 2017. The event was linked to research he conducted in the years prior, which examined the role that contemporary visual art practice plays in sociological and critical race theory discussions, specifically with regards to the notion of “whiteness“. Blight brought together a group of scholars, sociologists and philosophers for the conference, including the keynote speaker and distinguished American philosopher George Yancy.

However, as he ventured deeper into the subject, he quickly realised that there were more people who were challenging this notion of whiteness – many of them working across various different disciplines, such as portraiture, photography and montage. “The book itself is mostly visual, comprised of a sequence of images around a number of themes identified in my introductory essay,” explains Blight.

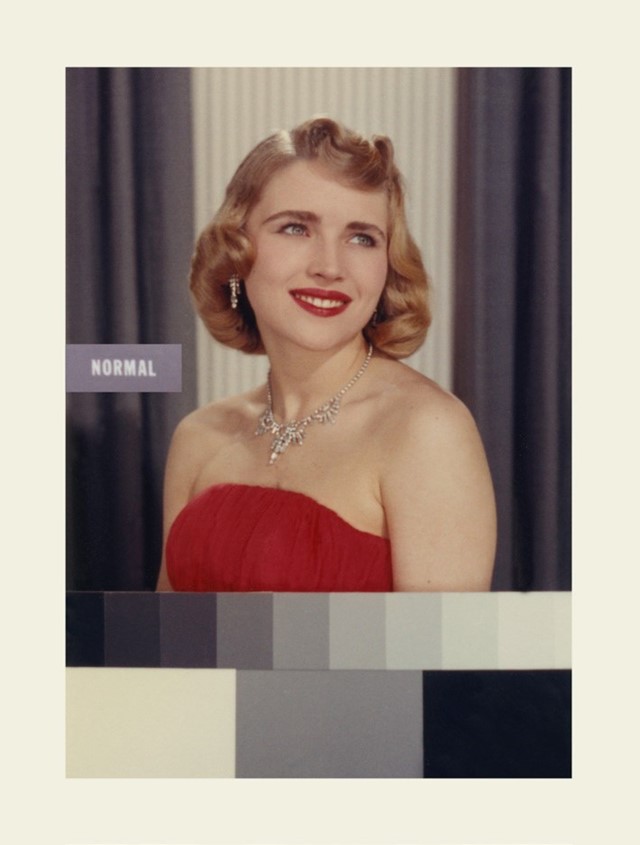

A core theme of the book is the bias of photographic technology – a medium created and dominated by white people, as an extension of “the white eye” – which plays an active role in reinforcing troubling narratives of whiteness. Blight includes images that disrupt this notion, with work from image-makers like Buck Ellison, Nancy Burson and Hank Willis Thomas.

The book also carefully explores the nuance and fluidity of racial whiteness. Blight explores how, historically, there have been many groups of people with white skin who were not generally seen as racially white (such as the Irish and people of Eastern European descent). The exclusivity of whiteness in this sense reinforced the notion that it was a class-based privilege, rooted in a discourse of racial purity. “Certain people historically have been invited to become white,” Blight explains. “For example, as explored by Noel Ignatiev in his book How the Irish Became White, when the English invaded Ireland, the Irish were considered ‘savages’ and therefore not white, despite sharing the same skin tone as their invaders. Similarly, the mass migration of Irish people to America led to a tense social scenario in which established white Anglo-Saxon Americans did not see the Irish as white.”

Asked to share his stance on the role that whiteness plays in society today, and what he feels should be done about it, Blight aligns himself with the “logic” of abolitionism. “Instead of trying to reform whiteness, I argue that we don’t need it in any way. It’s a kind of specious, violent invention that can’t be saved, effectively,” Blight says, finally. “Of course, there is a massive difference between having white skin and being racially white.”

The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization is co-published by SPBH Editions and Art on the Underground, and is out now.