A communist who staunchly believed in social and economic justice, Alice Neel painted nude portraits that challenged and subverted artistic convention

When Alice Neel painted herself nude at the end of her life, she was returning the favour that many of her subjects did her; laying herself bare, rendering herself vulnerable, offering up her soul. (“I’m a collector of souls,” as she once famously said). The image, which was created in 1984, when she was 80, was her first-ever stand-alone self-portrait. “It’s horrible”, Neel joked of the painting, which took five years to complete, “but she loved it”, according to curator Lucía Agirre.

The self-portrait is displayed at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao’s Alice Neel: People Come First, an exhibition that came to the Frank Gehry-designed building from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. People Come First focuses on Neel’s populist perspective. That word’s affiliations have warped over time, but in the case of Neel, it refers to her humanism, her commitment to portraying individuals disregarded by society. She favoured figurative painting as a means through which to accentuate her subjects’ unique qualities, from strength to vulnerability. Painting nudes was one way to achieve this more directly, to locate a person’s essence. Her choice of nude subjects also reflect her politics, as a communist who staunchly believed in social and economic justice.

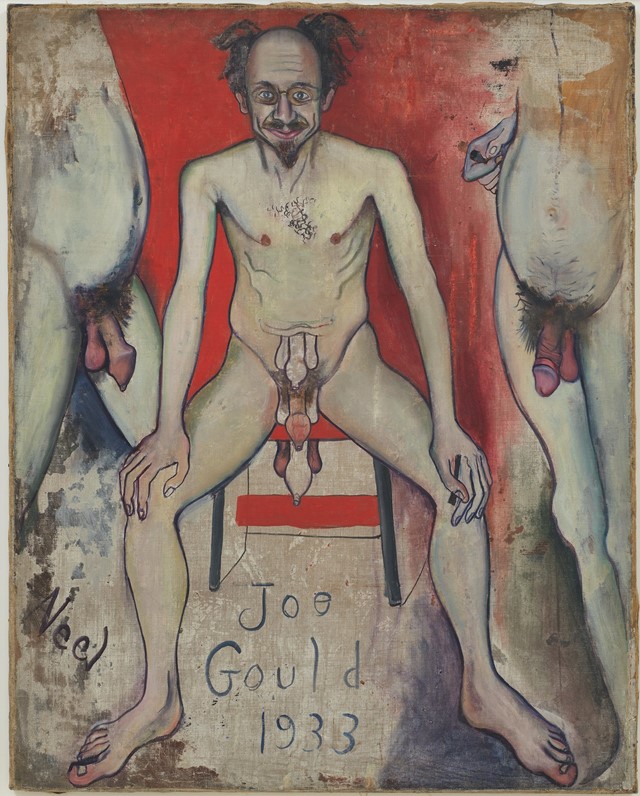

Among Neel’s radical nudes were her paintings of nude men. Neel set a precedent for painting male nudes with unapologetic irreverence. Her painting of Joe Gould, an eccentric and often homeless figure in New York’s Greenwich Village, where she lived in the 1930s, for example, portrays the subject flanked by penises. His own uncircumcised penis appears multiple times, depicted like the domes of Russian churches. “Everybody knew him because he was writing a book, An Oral History of the Contemporary World, which he never finished,” says Agirre. “Neel liked people who were different from the others and she wanted to show him in a way to reflect that.” Due to its explicit content, the painting was not exhibited until almost 40 years later.

Male nudes also appear in a series of paintings Neel made of her lovers throughout the 1930s. These erotic drawings, pastels, and watercolours include Alienation, which pictures Neel lying in bed before her long-term lover, John Rothschild. In another image, he urinates in the sink while she urinates in the toilet, a candid moment of pre- or post-coital intimacy. “It was revolutionary for a woman in the 1920s to exhibit her sexual agency in this way,” explains Kelly Baum, one of the curators of the MoMA show. “These images are no less political than her portraits of well-known communists.” The nude lovers also include José Negron, a caberet singer with whom she had an affair, and Kenneth Doolittle, a sailor who destroyed some of her paintings in a fit of jealous rage.

One of the images Doolittle is thought to have destroyed is of Neel’s second daughter, Isabetta who was separated from Neel when she was taken back to Cuba by her father, Carlos Enríquez. Neel painted the adult-like naked portrait of Isabetta after a rare visit. “I always had this awful dichotomy. I loved Isabetta, of course I did. But I wanted to paint,” Neel has said of the antagonism between motherhood and being an artist. Neel was preoccupied by motherhood as a subject, beginning her paintings of mothers and daughters in Cuba in the mid-1920s and later painting stages of motherhood including perinatal and postnatal pregnancy as a normalising gesture in a period when pregnant women were generally not yet depicted in artworks.

Pregnant Maria, 1964, is the first in a series of pregnant nudes she began the same year. Maria is thought to be a neighbour (Neel often painted neighbours, from Greenwich Village to Spanish Harlem). In the series, Neel exposes the physical pressures and emotional labour of motherhood while radically expanding the depths of female subjectivity as seen in art at the time. These mothers were not sanitised or Madonna-like but visceral and vulnerable.

Later in life, after achieving critical acclaim and moving to the Upper West Side, Neel continued to paint nudes including of art historian Cindy Nemser, who tells the story: “I wore my perfectly fitting stunning size 12 suede suit, which my husband had impulsively bought without me as a gift, and he had on a brand new outfit. Alice took one look at us, and frowned.” Neel – in her 70s – disapproved of how bourgeois they looked, gradually coaxing them out of their clothes.

“She asked many sitters to pose nude and in this painting she is making that request of herself,” says MoMA curator Randall Griffey of Neel’s famous self-portrait. “This was a statement,” Baum adds. “Neel was thinking about her legacy and the tradition of male artists’ late self-portraiture, from Picasso [Self-Portrait Facing Death] to Rembrandt. She’s stripped bare of pretense and relishes every aspect of her aged body.” As always, says Baum, Neel valued the taboo, or the opportunity to show us what the world tells us it’s not worth looking at. In the words of Agirre, “it was a final act of rebellion.”

Alice Neel: People Come First is at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao until 6 February 2022.