In a new book, curator and writer Catherine E McKinley explores the rich history of African photography, fashion and womanhood

Catherine E McKinley understands displacement and the power that a community has in bringing back a much-needed sense of alignment and belonging. Growing up in a largely segregated world as an adopted Black child, McKinley – a Fulbright scholar and author, who only had a small community of African women to look to for guidance – has a full grasp of what it means to not quite fit in, and to be in a constant state of curiosity when it comes to your ancestry.

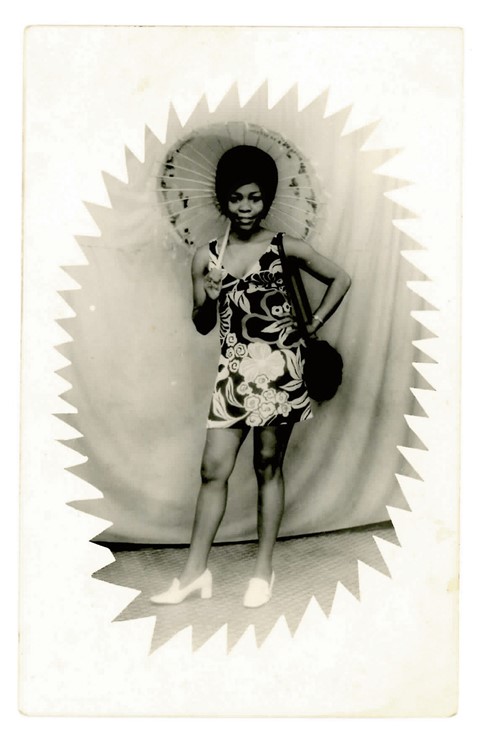

Through her photography book The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women, McKinley interrogates the history of African photography, and explores how the art portrayed and displaced the agency of African women between 1870 and 1970. This stunning work also provides a sweeping look into the fashion cultures present in those times, and details how African photography was slowly reclaimed from the colonial gaze.

McKinley started collecting images in 1991, with many of them being gifted to her while she was travelling through Africa. She then started collecting more over the years through galleries and auctions. This intimacy filters through the book, making it feel like both a necessary education on an underreported history and a nostalgia-inducing scroll through a forgotten family album. Here, McKinley tells AnOther about photography’s history in Africa, and why this kind of archive work is so important.

AnOther Magazine: Can you talk me through the process of this book?

Catherine E. McKinley: For the most part, putting the book together was an act of self-education. I was doing research for my other book Indigo, a journey along the indigo trade routes in 11 West African countries, and realised that a lot of the archives on African fashion history are poorly preserved or simply revised so that they are Europeanised. Then I met Seydou Keïta in 1996 on the night that I was leaving for Mali; it was at the opening of his show at Gagosian Gallery. His photos were as big as the gallery wall and unlike anything I’d ever seen. Everything that came before was largely anthropologised or poverty porn, or, as a counterbalance, highly constructed mythic kings and queen images from the African-American press. But Keita’s images were just the most magnificent thing I’d ever seen. Although I didn’t think of myself as a collector, I was already collecting African-American and African art – often figurative art – and that moment turned my focus on photography.

AM: The agency of African women is a strong theme in this book. You touch on how they were at one point exoticised, and then much later captured with a bit more range, even though African men were usually behind the camera.

CM: African women have always been disproportionate in the archives. The colonial images repeated the same typologies for African women: the maternal figure; the domestic worker; workers of the land, etc. When I discovered these studios where women were portrayed very differently, showing these free, full personalities, I couldn’t take my eyes off of them and the fashions they displayed at the time. It was also really about looking for foremothers to understand what their lives were and putting them against the women I grew up around, whose stories always fascinated me.

AM: Do you have any favourite photograph in the book that captures women away from the colonial gaze?

CM: All the photographs in the first pages of the book really stuck with me. I always pick out the photos via an intimate process. With each photo, there is something about the person – the look in their eyes, the feeling in their face – that just draws me to them. In a way, it’s like walking towards a person in the street and having your spirit connect with them.

AM: The book impresses on the importance of not just documenting, but doing it accurately, can you speak a little on that?

CM: As someone who is interested in things that have disappeared and or are disappearing – in this case, textiles, fashion or photography – I am thinking of this work partly as an act of documenting. At the same time, I also think of it, as Edwidge Danticat remarks in the introduction, as a community album, where everyone can find themselves. I see this work as a way to begin to have important cultural conversations between Africans and African-Americans and other diasporans about what this history means to all of us and the consequence of understanding it.

AM: How do you think this work will go on to inform how people relate to African fashion and its history?

CM: The history of African fashion is so long and so complex, and you do hope that people will study it more. I think many of those using African materials tend to fall back on wax clothes or traditions in contemporary fashion photography and it just becomes the trend. But I think African fashion deserves much more attention on what those designs are built upon. We tend to call things African so quickly without always knowing what the specific history is and the history is fascinating and hybrid. The “African” part of it is usually so much deeper and more about intellectual heritage than credit is given.

AM: Do you think there are traces of the colonial gaze still functioning in how African fashion and photography are engaged with today?

CM: We can call it colonial or we can call it a western gaze. And yes, the western gaze still operates. But the western gaze is not solely a white gaze. In the American context, it is a collision of white dominant media, but also the countless consumers and creatives who are people of colour who help to drive it. The works being created right now and put in the global marketplace are not absent from western commercialism, whether they’re influenced by African works or not. Even when you are photographing an opposition to a gaze, we are still engaging it and I really think that, through studying, we can come to be more deliberate with what we are doing and make good on our chatter. The ways we engage are often swept up in very simple politics, and investigating that helps us understand the power between who is behind the camera and who is in front of it.

The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women is released next month through Bloomsbury