The animation godfather has inspired a global, mixed-media cohort of creators – here, five contemporary artists trace their ideals and inspirations back to Miyazaki’s pen

By legendary animator Hayao Miyazaki’s own matter-of-fact calculation, he is “not a storyteller, [but] a man who draws pictures”. Even if obligatory humility, the quote speaks to his rare place in moving-image history. Is he a mass-media wizard, with a body of work that, by one mind-bending statistic, has reached 96 per cent of people in Japan? Or is he an artist’s artist in his sweat-the-details temperament and allegiance to analogue techniques? An auteur, or an artist, full stop?

If not as quantifiable on his box-office record, Miyazaki’s impact as an artistic institution is surely worth considering – especially now, as his company Studio Ghibli enters a visual-paradigm shift. Long a stalwart against Pixar-ification, the studio just released its first all-CG film, Earwig and the Witch, on HBO Max.

Miyazaki may be a man who draws pictures at heart. But his work transcends discipline and industry, as the following survey suggests. Here, five contemporary artists trace their ideals and inspirations back to Miyazaki’s pen.

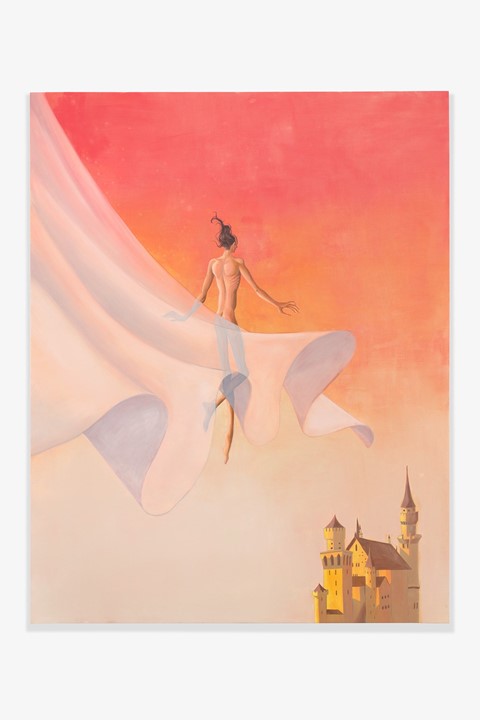

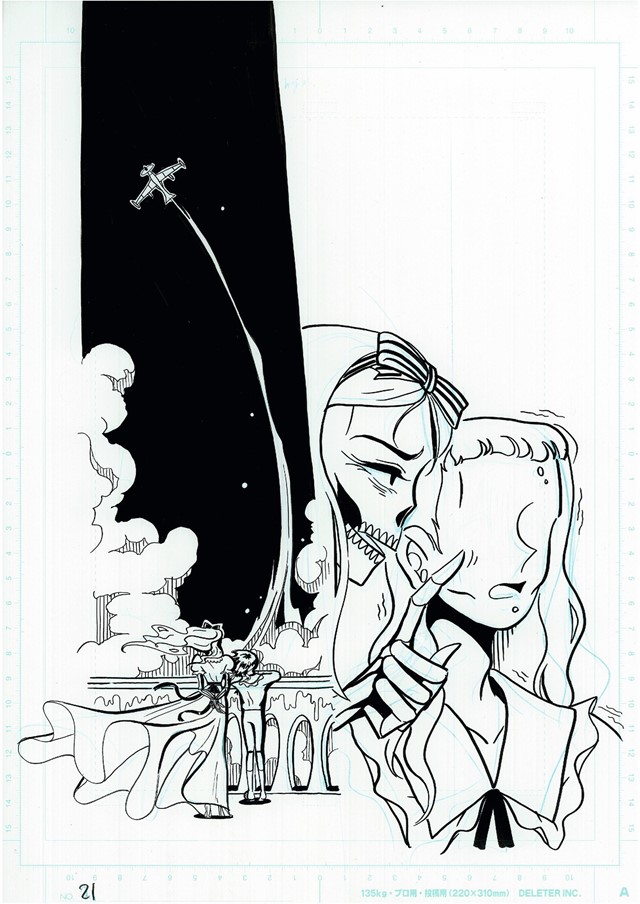

Julien Ceccaldi, painter and comic artist

“The first Miyazaki production I ever saw was Sherlock Hound, a Sherlock Holmes steampunk adaptation with anthropomorphic dogs. Then I watched Princess Mononoke, after reading about it in the French manga magazine Animeland. As for a favourite, it’s between Kiki’s Delivery Service and Porco Rosso; I can watch both over and over. They’re less grandiose in scope than blockbusters like Spirited Away or Nausicaä, but I think they offer a deeper, more nuanced look into the psychology of their characters. I love the melancholy of these films, and how they contemplate the passing of time. And Kiki, in particular, for its depiction of depression and creative block. I can relate to Miyazaki’s creative process, in that I work in panic mode, and fully alone. I should try his habit of shouting ‘Good morning!’ into empty rooms. It might help fire me up for the day.

“Last year, I made a painting referencing the air-walking scene in Howl’s Moving Castle. I wanted the viewer to imagine that specific motion – walking on air, as opposed to floating or flying. Except here it’s not a couple, but just a skinny, bald gay guy. In Howl’s, war is ubiquitous, even when it’s happening off screen. I hoped to replicate that feeling of dread in Solito, where this prince-like character seems dreamy, but is also [suggestively] involved in a deathly war.

“The background art in this new Studio Ghibli movie, [Earwig and the Witch], has a hand-painted touch, which we love. But it’s true the characters seem a bit unsettling and out of place; their rendering takes me out of the universe a little. But we’ll see!”

Monster Chetwynd, sculptor and mixed media artist

“I discovered Hayao Miyazaki in my late 20s, when I noticed my brother Aaron watching Spirited Away on repeat. I’ve loved Nausicaä for ages for its green politics and how well the visual metaphors work. Howl’s Moving Castle blew my mind, though I was shocked to read the book and find that I actually preferred it to Miyazaki’s adaptation. Diana Wynne Jones’s novel is even more bewitching and intense.

“At Ladyfest at Goldsmiths College a few years back, I gave a presentation called, Are Ghibli Studio Films Sexist? One of the questions it posed was, ‘Is representation enough?’ We looked at empowered characters, like Fio Piccolo from Porco Rosso; she is a young and snazzy engineer. We also looked at the prevalence of skimpy clothing among Miyazaki’s women. All those in the audience over age 25 said they were satisfied to just see girls as protagonists, and all under 25 said this was not enough.

“When I watched My Neighbor Totoro, I fell in love with the Cat Bus; if there was going to be a Tax Haven Run by Women then we would need the Cat Bus to get there. I decided to build my own Cat Bus – one that could be lifted and operated by real people. I worked on it for over six months, in a garage-type space. As I was sewing away one day, a delivery man stopped to tell me how stressed he was. When he saw what I was doing – which at that moment was applying Cat Bus’s smile – he said, ‘Let me inspire you.’ His face broke out in this huge elated grin, which he wore all the way back to his van. I thought, my Cat Bus is already working its magic!”

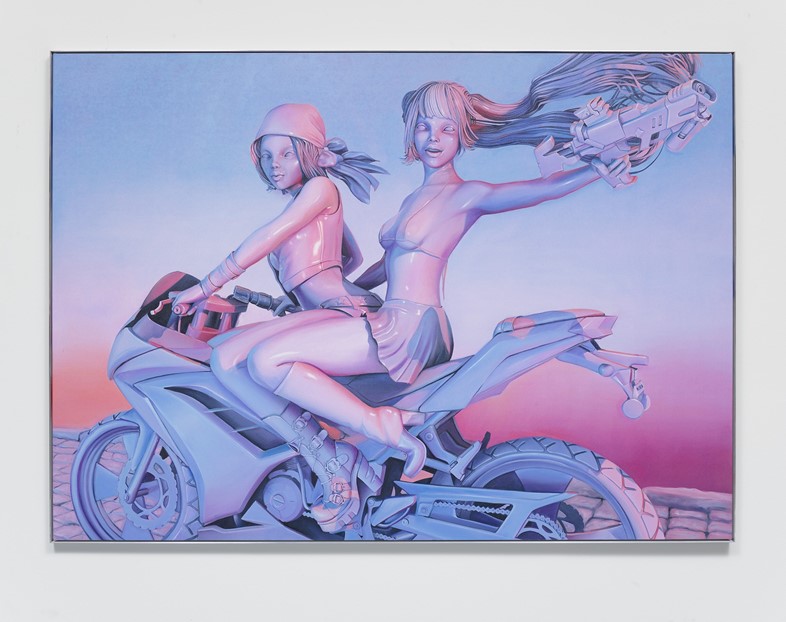

Emma Stern, painter

“I was ten when Spirited Away came out, in 2001. I had already developed a healthy, rebellious disdain for my parents; I thought [the idea of them] turning into pigs was actually pretty cool.

“The first drawings I ever made were just copies of my favorite TV and movie characters. These included Miyazaki’s female protagonists – especially Kiki, from Kiki’s Delivery Service. They’re mischievous and adorable but also smart and savvy and flawed and vulnerable. The ‘heroines’ I create in my own work are of a similar vein; there is something a bit mystical about each of them. They’re at once familiar and otherworldly.

“In the Studio Ghibli documentary, Miyazaki says something pretty bleak and to the effect of, ‘Even if the intention is to simply make something beautiful, every technology is eventually implemented towards war and destruction.’ I think he has a really complicated relationship with technology, which I guess is why this upcoming 3D film is such a big deal for the studio. I am much more optimistic about technology as a force for good, but I can relate to Miyazaki’s resistance to embrace it entirely. Although technologies like 3D modeling are an essential part of my practice, the final product is a painting in the most traditional sense: steeped in tradition and bogged down by its own canon. The phrase gets overused, but as artists, we do truly find ourselves in a liminal space – in mid-transition. Some let go easier than others, and some don’t let go at all.”

Alex Anderson, ceramicist

“I first discovered Miyazaki’s work in my sophomore year of college. My roommate showed me My Neighbor Totoro, which became an instant favourite, along with Howl’s Moving Castle and Spirited Away.

“Miyazaki’s work, as well as the Superflat movement in contemporary Japanese art, have significantly influenced my work; both create a complex somatic space of beauty and dreams that vacillates between the wonder and melancholy of the human experience.

“I do see immediate parallels between my and Miyazaki’s work. I think we both approach the human condition with a focus on evoking emotion through whimsical and surreal narratives. These only make sense in their own world and context, yet exist as throughlines across productions: films for him, exhibitions for me. We both assign human qualities to inanimate objects, and both our works can feel poignant and idyllic, yet aware of the violence and iniquity of the world. An understanding of danger and evil precludes these narratives from being overly saccharine, even though they access the tenderness at the core of our emotional worlds.

“From what I’ve seen of [Earwig and the Witch] – which is just the trailer – the CG element pushes the work more into the realm of Tim Burton, who is another favourite of mine … It also makes the aesthetic of the film feel more Western, and may shift how we receive the content. In Miyazaki films, we expect magical realism, surrealism, loss, and sweetness. In a way, the CG element disrupts any such expectations. This may allow us to see a new ‘Miyazaki’ in the work, but I do prefer the previous hand-drawn animation.”

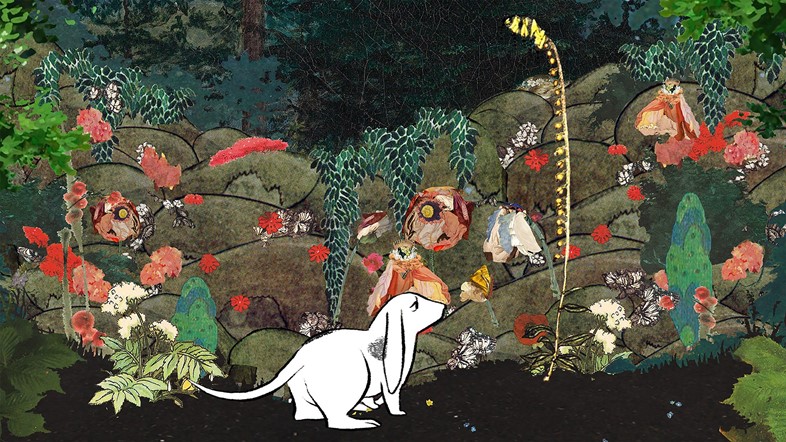

Rachel Rose, video artist

“As a kid, I watched a lot of stories about changing landscapes, and the lost pasts they possess: stuff like The Last Unicorn and Fern Gully. So, of course I was drawn to Princess Mononoke.

“In all Miyazaki’s works, you can feel how he intuitively uses minute detail to develop the story. I think of water moving a leaf across a pond, or wind moving a blade of grass. Or full seconds spent on tenderly rendered images of food. Boiling pasta really means something when it’s taken 12 frames per second to [animate] it – and the viewer can sense that hand-to-image application.

“Miyazaki lets large and small scales inform one another: after aerially showing the debris of an entire city destroyed by an earthquake, he pauses [to let] one pebble settle. In this quiet action, the whole city feels folded into the pebble. I think about that succession of shots always.”