The pair discuss their new book, Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof, which celebrates the ‘love, trust and honesty’ shared between artist and subject

In October 2019, Kingsley Ifill packed up his bags and flew to Los Angeles. The Kent-based artist and photographer was heading for the Hollywood Hills, where he would meet fellow UK creator Danny Fox in an empty house. The pair had made a plan: they would stay in the space for four months and create an intimate art project based on their serene, suburban surroundings.

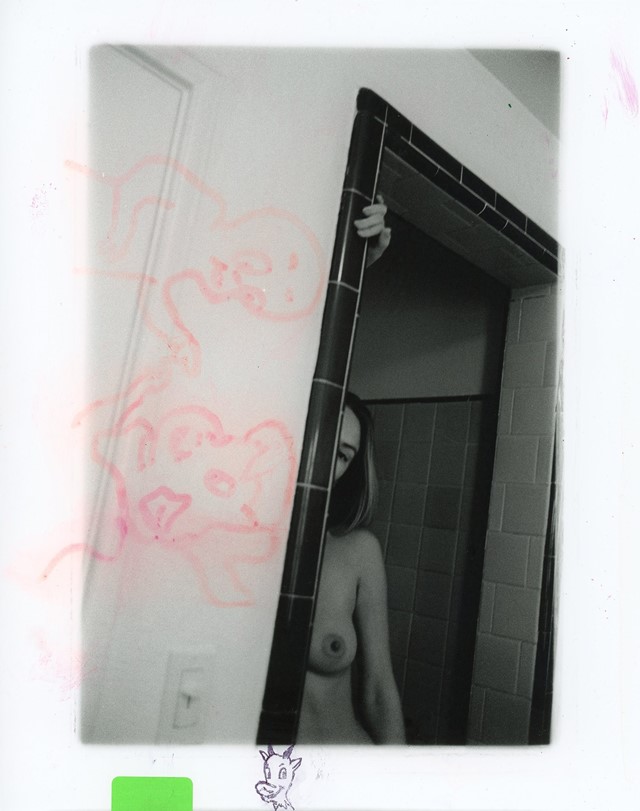

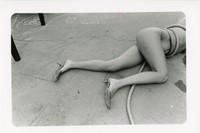

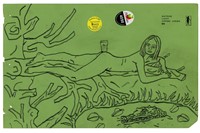

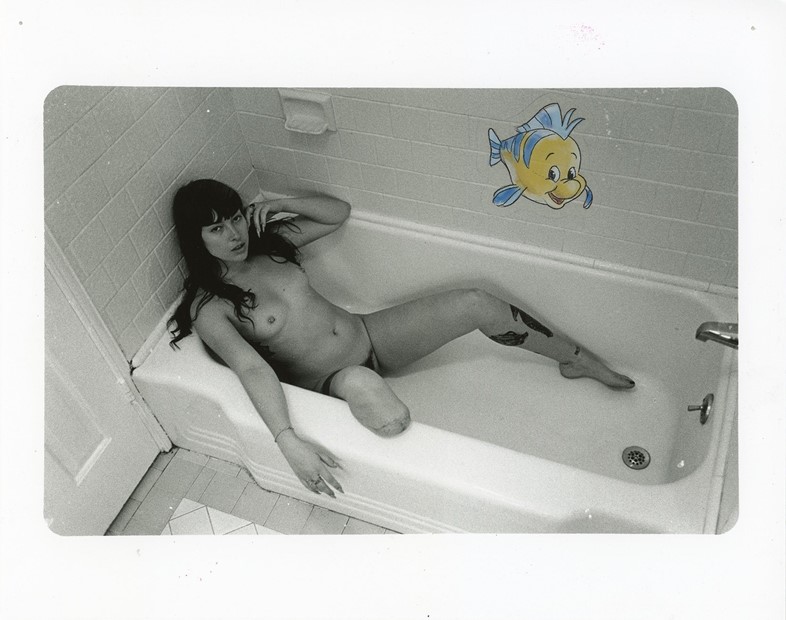

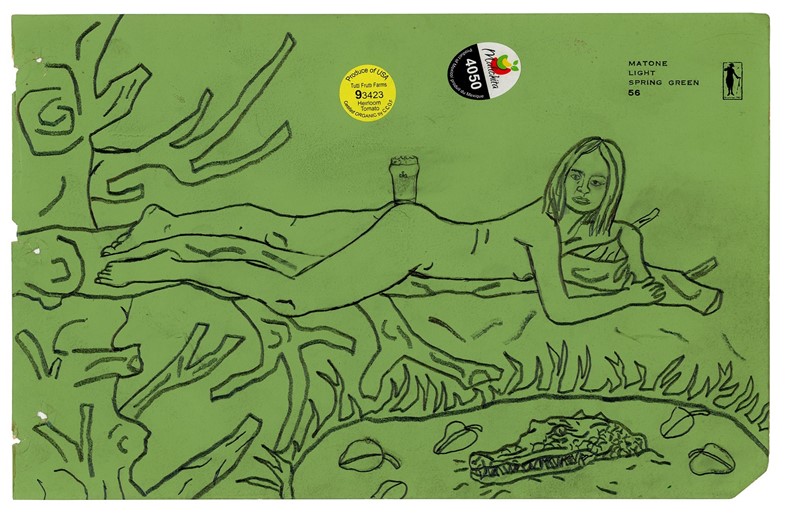

Over that time, friends and fellow artists would come and visit the house, with many offering their bodies as subjects. Fox and Ifill – the former being known for his vivid, figurative paintings and the latter for his darker, mixed media work – would then collaborate, combining their styles to create a fresh new take on the traditional nude.

The work can now be seen in a new book, Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof, which is published this week by Tarmac Press. It features a number of figurative studies, with subjects of all genders, interpreted through a mixture of photography, collage and drawing. For the artists, these pieces serve as a soft beacon of light in a world that’s dimmed by negativity and confusion. They’re a celebration of the love, trust and intimacy that lies between artist and subject, as well as a jolting reminder of the impermanence of youth. “[Our bodies] are pretty ordinary really,” Fox tells AnOther. “It’s the short burning time that we are in them that’s interesting.” Here, in a conversation conducted over email, both Fox and Ifill explain more.

Dominique Sisley: Can you tell me a little about how this collaboration came about? Why did you decide to work together on this project?

Danny Fox: Speaking for myself, I wanted to create some new figurative source material to paint from. Reference photographs for body and form. Kingsley appeared in the doorway of my studio and we had the same idea at the same time. Is that how you remember it, [Kingsley]?

Kingsley Ifill: I can remember spending the whole night without sleep before flying to LA, trying to work out how to pack a darkroom into a suitcase. Arriving in the evening, with a plan to stay for a couple of months, with no other plans other than to be there. I can remember [Danny] giving me a Facetime tour of the house, viewing it with the real estate agent. I remember the darkness in the basement when it took a while to find the light switch, and you saying it could be a darkroom. Then the morning after arriving in the late evening, standing in the doorway, with the thought of the two months ahead, it wasn’t “what shall we do” we asked each other, rather “what shall we make”. And the contrast of the new environment from that which I was used to visiting you. Seeing people pushing needles into their arms on Skid Row had been traded for gardeners blowing leaves down streets that smell of wet grass rather than human shit and piss. A new season. Change was in the smog, and for the first time, I started to see it in faces which had materialised into moments. “What shall we make?”… one plus one sometimes equals three.

DF: The collaboration itself didn’t need too much thinking about. We’ve been working alongside one another for a long time now, ideas get traded, borrowed and stolen all the time so it was easy to arrive at a place where we both had control of the same picture, momentarily.

KI: Within transition lays translation.

DS: What do you enjoy about each other's work?

DF: Kingsley was photographing the blurred nights and days of 2010’s London when I met him, so I was probably a subject of one of his photographs before I’d ever seen any of his work. When I did see the work I thought he had that rare ability to capture the way it really went down, but what I later realised was that he captures how it feels to actually go through it, which is that I’ve always wanted to do with painting.

KI: From the get-go of meeting Danny and seeing his work, I’ve always admired the honesty and sincerity. His ability to tell a story through an image. Easier said than painted. His paintings and drawings read to me more like poems, he’s a master of creating gaps and traps. Letting you in, but locking you out. Photographs can act like signposts between those spaces. Showing you where to go, but not explaining how to get there.

DS: And what about this book? Why was it important to make at this time?

DF: It really comes down to making something out of nothing. In the early days we made art out of the bar life because that was what was happening. We were young and out looking for the action and that shows in the work. Now a decade on and a world apart, an empty house in the Hollywood Hills, it’s really just honouring that deal we made all those years ago to keep making art out of the surroundings we find ourselves in.

KI: You can’t decide the period that you’re living in. It’s my understanding that an artists purpose is to record the time in which they exist. Some artists will sugar coat that up to their eyeballs, but fundamentally, it’s not so complex and in one way or another, on the great plain of time, we’re all just adding handprints to the same cave. Or spit to the wall. However, perspectives shift and within the collective gaze, there’s a maze. Where all you can do, is show how you saw, when you could see.

DS: What is about nudes that you find so compelling? And what do they express in this book?

DF: We studied the nude in art intensively, covering the house walls with references xeroxed in The Brand Library – from early pioneers and 19th-century French studio photography by anonymous photographers, up to the contemporaries that they had influenced. It’s not that nudes are so compelling, they’re pretty ordinary really, we all have a body. It’s the short burning time that we are in them that’s interesting. To me, it seemed there was no better way to express a fleeting, impermanent moment than the young body, especially the young bodies of the friends and artists that hung around that empty house in Hollywood.

KI: I like the part in Lorraine [Nicholson]’s intro to the book, where she explains that the bodies appear to her at a point of ripeness, after the hardness of youth, but prior to the sourness of old age. Some kind of peak, if there was one, here nude in a state timelessness. Isolated figures appearing peaceful within their solitude. As if they’re waiting around in some kind of limbo that could be holding hands with any other images of a similar nature from a completely different time. Showing us, this is what living is. Simply, living. Joining up the dots, from dot to dot, or not.

Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof is available now, and published by Tarmac Press